Capitalisn’t: The Capitalisn’t of Crypto—SBF and Beyond

Reporter Zeke Faux discusses crypto and the conviction of FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried.

Capitalisn’t: The Capitalisn’t of Crypto—SBF and BeyondShort-sellers—who sell borrowed shares on the expectation that prices will fall—are often accused of wreaking havoc on asset prices. Outcry has led regulators to restrict short selling, as they did in July and September 2008, shortly before and after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

But such restrictions cause investors to pay more for credit, reflecting higher risks, according to Chicago Booth’s Mark G. Maffett and Emory University’s Edward Owens.

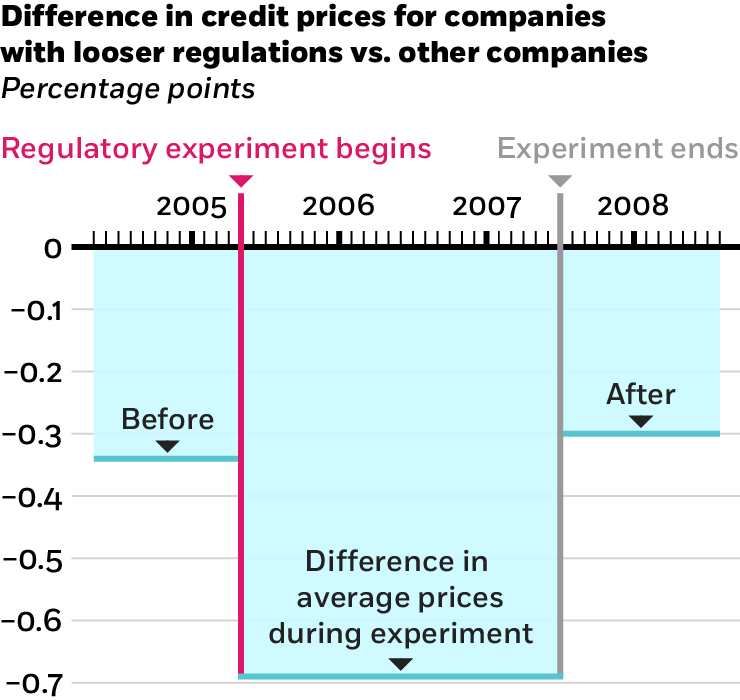

Their analysis exploits an experiment conducted by the US Securities and Exchange Commission from 2005 to 2007 in which short-selling restraints were loosened on a random third of the companies in the Russell 3000 Index.

Looser regulations, cheaper credit

When the SEC loosened short-selling restrictions for a random group of stocks, the companies’ credit-default-swap spreads became lower than those linked to companies that were not part of the SEC program.

Maffett and Owens, 2017

Maffett and Owens looked at the market for credit-default swaps, financial agreements that protect buyers from default risk in return for a payment stream known as the spread. CDS spreads reflect the likelihood, according to the market, that a company will default.

The researchers find that companies in the SEC program had lower CDS spreads, meaning that credit prices were lower. Companies with fewer short-selling restrictions had spreads that were priced around two-thirds of a percentage point below those of companies not in the program.

The researchers also studied short-selling bans imposed around the globe, examining country-by-country differences in the proportion of a company’s shares that are borrowed relative to market capitalization. They find that more extensive short-selling constraints were correlated with higher CDS spreads. During the periods studied, stocks that were exposed to a ban had CDS spreads significantly higher than at companies not affected by a ban.

Taken together, the analyses by Maffett and Owens suggest that trading restrictions in the form of limits on short selling lead to higher credit prices. “Our evidence suggests that short-selling constraints not only keep public information out of equity prices, but also reduce the incentive to acquire private information,” Maffett and Owens write. Investors and market participants pay more as a result.

Mark G. Maffett and Edward Owens, “Equity-Market Trading Restrictions and Credit Prices: Evidence from Short-Sale Constraints around the World,” Working paper, November 2017.

Reporter Zeke Faux discusses crypto and the conviction of FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried.

Capitalisn’t: The Capitalisn’t of Crypto—SBF and Beyond

Most consumers support ‘private sanctions’—even if it costs them money.

On Russian Aggression, Americans Want Companies to Vote with Their Feet

Disclosure can backfire by driving small companies to stop innovating, research suggests.

Mandated Financial Disclosure Leads to Fewer Innovative CompaniesYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.