Infographic: A Better Measure of Collectivism

Survey evidence affirms a clear cultural divide between East and West.

Infographic: A Better Measure of Collectivism

Nudges” are behavioral-finance parlance for little cues that urge us to do things at certain times, and have been embraced by governments and organizations to influence behavior. For example, when you pay a restaurant bill with a credit card, a list of suggested tip amounts can nudge you into tipping at least 15 percent. When you sign up for a retirement plan, the company may precheck a box to nudge you into participating.

Now research suggests people may respond as well to “numerical nudges,” which are dynamic and changing but inherently meaningless numbers that can nevertheless be used to strategically alter behaviors.

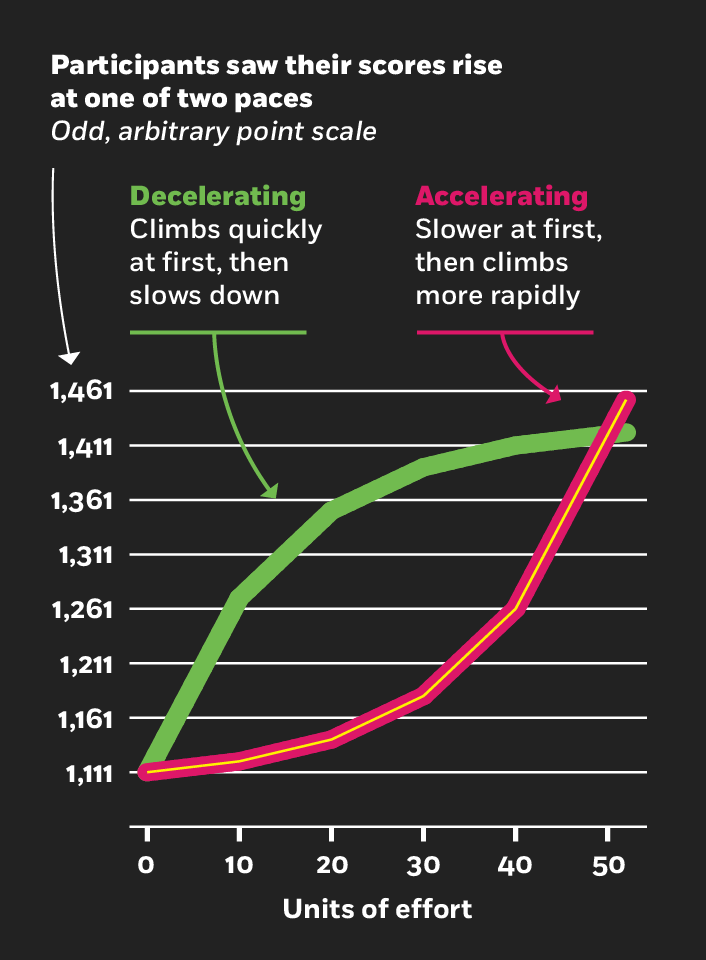

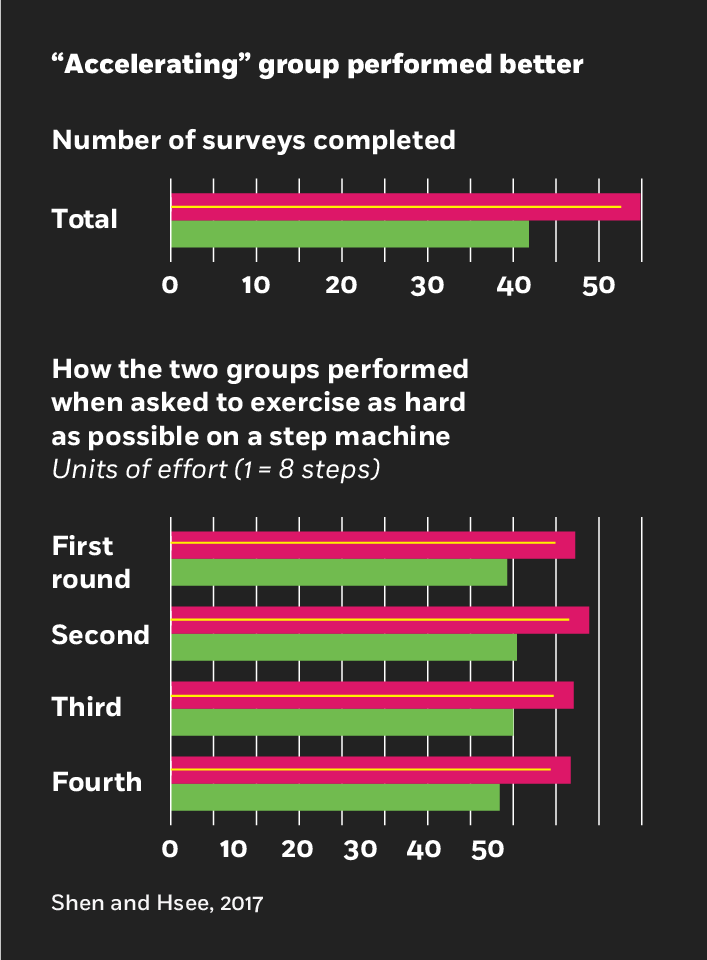

Chicago Booth’s Christopher K. Hsee and Luxi Shen of the Chinese University of Hong Kong ran several experiments designed to test numerical nudges. In one, the researchers had people complete online surveys rating advertisements, telling participants that the three people who finished the most surveys would receive a cash prize. For every survey completed, participants received a score, which was essentially spurious: it did not indicate anything about a person’s performance and could not be exchanged for any reward. But participants responded to the scores anyway. People who saw their point total accelerate quickly filled out significantly more surveys than those who saw their total climb more slowly.

Another experiment tested men who were doing several two-minute rounds on a step machine. Such machines typically track the number of steps a person takes while exercising, but the researchers adjusted some machines to display an extra number that increased according to a preprogrammed algorithm. “Notably, this number carries no independent information,” the researchers write—and they told the men as much. Yet once again, participants who saw their “X number” scores rise faster as the task went on climbed more steps than others.

A variety of organizations could use numerical nudging to influence behavior, the researchers say. For example, retailers could give shoppers a score for repeatedly buying the same product. If a person sees the score climb quickly after he purchases a specific brand of soap, for example, he may buy even more of it on his next shopping trip. An accelerating number, says Shen, could be used to motivate people to pay bills on time, save energy, invest in retirement accounts, and more.

Christopher K. Hsee and Luxi Shen, “Numerical Nudging: Using an Accelerating Score to Enhance Performance,” Psychological Science, June 2017.

Survey evidence affirms a clear cultural divide between East and West.

Infographic: A Better Measure of Collectivism

Most people agree that deception is ethical in these situations.

Eight Ways in Which Lying Is Seen as Moral

An excerpt from the updated edition of the bestselling book.

Nudge: Preface to the Final EditionYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.