How Some Experiments Use Emails to Control for Systemic Bias

Researchers put a twist on a classic experimental design.

How Some Experiments Use Emails to Control for Systemic Bias

Ben Wiseman

Finland sits at the top of the United Nations’ 2018 World Happiness Report, which ranked more than 150 countries by their happiness level. The country that gave the world the mobile game Angry Birds scored high on all six variables that the report deems pillars of happiness: income, healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom, trust, and generosity. News reports touted Finland’s stability, its free health care and higher education, and even the saunas and metal bands for which it’s famous. But some also pointed out that Finland’s GDP per capita, at $43,000, is lower than in some other countries; GDP is $57,000 in the United States (happiness report rank: #18) and $71,000 in Norway (#2). “The Finns are good at converting wealth into wellbeing,” Meik Wiking of the Happiness Research Institute in Denmark told the Guardian.

Yet abundance does not equate to happiness, according to research—even on a longer time frame. In most developed countries, the average person is rich by the standards of a century ago. Millions more people have access to safe food, clean drinking water, and in most cases state-funded health care. And in countries with a growing middle class, millions more are now finding themselves able to purchase big-screen televisions, smart phones, and cars. But this growth in wealth hasn’t made people happier, University of Southern California’s Richard A. Easterlin first argued in 1974. In January 2016, after researchers challenged what’s now known as the Easterlin paradox, he reexamined the data and concluded that it still stood—worldwide long-term trends in happiness and real GDP per capita were largely unrelated.

People, it appears, want more than money. Some of what they want, such as free health care and living free from corruption, is determined on the social and governmental level—and helps explain why Nordic countries dominate the top spots of the worldwide happiness rankings. But there’s still hopeful news for citizens of the United Kingdom (#19), France (#23), Brazil (#28), Saudi Arabia (#33), China (#86), and elsewhere. Research suggests that it is within people’s power as individuals to achieve more happiness. Chicago Booth’s Christopher K. Hsee is a behavioral scientist focusing on what he calls hedonomics, derived from the Greek word hedone, or pleasure. Hsee views hedonomics as a counterpoint, or complement, to economics. Rather than studying how to produce more “stuff,” hedonomics studies how to extract more happiness from the existing stuff.

“Our ancestors had to work to accumulate enough to survive. But now productivity is so high, we don’t need to work so hard for survival,” Hsee says.

Long before Thomas Jefferson embedded “the pursuit of happiness” into the Declaration of Independence, classical philosophers such as Socrates, Aristotle, Buddha, and Confucius waxed lyrical about how to achieve happiness. In the early 20th century, Sigmund Freud posited that a driving force to seek pleasure was rooted in the id, the most animalistic part of human nature. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, argued that people want more than basic pleasure; they want meaning and purpose in their lives.

The more recent studies of happiness are both more precise and perplexing. Empirical studies have explored what makes us happy. Is it experiences? Time? Princeton’s Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, both Nobel laureates, in a 2010 study find that annual income and day-to-day emotional well-being were correlated only until around $75,000. After that point, increasing income produced no more emotional well-being—leading the researchers to conclude that high income doesn’t buy happiness. “During the past 10 years we have learned many new facts about happiness. But we have also learned that the word happiness does not have a simple meaning and should not be used as if it does,” notes Kahneman in his 2011 book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. “Sometimes scientific progress leaves us more puzzled than we were before.”

Six keys to happiness

The United Nations’ annual World Happiness Report incorporates quality-of-life factors beyond money to measure global happiness.

Researchers now study different kinds of happiness, and their work falls into essentially two camps. One focuses on overall well-being, or life satisfaction, which can involve factors such as money, religion, politics, culture, and marriage. The other looks at shorter-term happiness derived from consuming certain things. This is the branch that includes hedonomics, as well as more general judgment and decision-making. Chicago Booth’s Richard H. Thaler, a Nobel laureate, coined the term “hedonic editing” in the 1980s, when he started to explore how people could make decisions to maximize their happiness—for example, by spreading out fun events over time but scheduling unpleasant ones back-to-back.

A 2005 paper by University of Central Florida’s Peter Hancock, Aaron A. Pepe, and Coventry University’s Lauren Murphy was one of the first to use the term “hedonomics,” which originally referred to the study of ways to interact with machines, a still-topical issue as automation and artificial intelligence merge.

Hsee and his Chicago Booth colleague Reid Hastie redefined the term in 2008. Their version of hedonomics is premised on the idea that people don’t need more resources to be happier; they need to use existing resources differently. For example, suppose a child initially enjoys playing with wooden blocks but grows tired of them. Hedonomics suggests the child doesn’t need more blocks to be happy; she needs to change how she plays with those blocks.

If not blocks, say a person has 20 pieces of chocolate. To optimize happiness, consume them over several days, not all at once, explains University of Florida’s Yanping Tu, a recent Chicago Booth PhD graduate. The same principle applies to experiences. Instead of binge-watching a TV show, watch two episodes per day. Or better yet, apply a more sophisticated method: say you have six episodes to watch. You could watch two a day, or you could watch one on the first day, two on the second day, and three on the third day. That’s an improving sequence. Or you could do the reverse, in a decreasing sequence, by watching three at the start and winding down. “Hedonomics would suggest you take the first approach, arrange consumption in improving order,” says Tu.

Instead of optimizing their resources, many people instead seek to add resources. Hsee, who has devoted much of the past decade to researching hedonomics, says that can backfire and lead to a phenomenon known as the “hedonic treadmill.” This phrase, coined in 1971 by the late Philip Brickman of Northwestern University and the late Donald T. Campbell of Lehigh University, refers to the psychoeconomic version of a rat race.

What sets the top 10 apart

GDP and social support explain more than half the difference between the top and bottom 10 countries in the 2018 World Happiness Report.

Hsee, who grew up in China, recalls when “just having the ability to buy a cheap bicycle” in his city was a big deal. But by 2012 in China, according to the UN World Happiness Report, “virtually every urban household had, on average, a color TV, air conditioner, washing machine, and refrigerator. Almost nine in ten had a personal computer, and one in five, an automobile.” Hsee sees his friends, some now able to afford expensive cars, stuck on the hedonic treadmill as they seek to maximize their well-being.

The problem is that it takes more and more things to make people happy. In a recent study, for example, Hsee and recent Booth PhD graduate Raegan Tennant find that upgrading the screen size of an e-reader from medium to large made people happy initially, but over time the happiness faded. (See “Why a bigger house doesn’t always make you happier,” below.)

The hedonic treadmill fires up because people misunderstand what will actually make them happy, research suggests. People gain more happiness when they satisfy their inherent rather than learned preferences—needs rather than wants.

Hsee and a group of researchers—University of Florida’s Yang Yang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Naihe Li, and Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Luxi Shen, a graduate of Booth’s PhD Program—interviewed residents from 31 Chinese cities during one winter, asking how they felt about the temperature of their homes as well as the jewelry they owned. Home temperature was meant to signify an inherent preference, more of a biological need, whereas jewelry represented a preference developed in a cultural and social context. These learned preferences drive why someone might pick a French wine over a California wine, or a Gucci over a Coach bag.

When it came to inherent preferences, warmer room temperatures in the winter made people happier. This was true both within a given city and across cities: for example, within Tianjin, people with warmer home temperatures were happier—and on average, residents in Tianjin, where most homes were heated, were also happier than residents in Nanjing, where home heating was less prevalent.

But when it came to learned preferences, more expensive jewelry made people happier only within a given city, not across cities. Within Nanjing, people with more expensive jewelry were happier, but the average resident of Nanjing, who owned more expensive jewelry, wasn’t any happier than the average resident of Lanzhou, who owned less expensive jewelry.

“How warm the temperature is in relation to your happiness is absolute; it does not require social comparison. By contrast, how much jewelry makes you happy is relative; it requires social comparison,” Hsee says. A person is unlikely to compare herself to someone halfway across the world, but her envy and unhappiness are likely to increase if her immediate neighbors possess more than she does.

And the happiness generated by fulfilling needs lasts longer. Tu and Hsee asked people to recall a purchase—durable, and between $50 and $500—that they’d made in the previous year. Then the researchers asked how happy people had been after making the purchase, and how happy they were at the moment of the study. Regardless of which preference the purchase satisfied, inherent or learned, people’s happiness declined over time—but it was more persistent if the purchase satisfied an inherent preference.

Less of a decline

Assessing people’s happiness with significant purchases, the research reveals more staying power in fulfilling needs rather than wants.

Balancing needs with wants can take many forms. Say a person has some money to spend and already has a heated home. In that case, should she buy jewelry and handbags, or invest in something else such as a shorter commute? Some research suggests that time gained or lost in commuting is closer to a need than a want. University of Basel’s Alois Stutzer and Bruno S. Frey find that people who commuted long hours had higher incomes, but in terms of happiness, the extra money didn’t compensate for the time lost.

“Each of us has only a fixed amount of time available for family life, health activities, and work. Do we distribute our time in the way that maximizes our satisfaction? The answer, I believe, is no,” writes USC’s Easterlin. “We decide how to use our time based on a ‘money illusion,’ the belief that more money will make us happier, failing to anticipate that in regard to material conditions the internal norm on which our judgments of well-being are based will rise, not only as our own income grows, but that of others does as well. Because of the money illusion, we allocate an excessive amount of time to monetary goals, and shortchange nonpecuniary ends such as family life and health.”

Most people obviously move to satisfy their needs first and then, after those are met, move to satisfy their wants. After all, once you have a heated home, why not want the Gucci bag? The problem is that the happiness that people get from addressing needs lasts longer than what they get from addressing wants, leading to a state of regular dissatisfaction. In this way, instead of turning off the treadmill, many people turn it up, and can find themselves in a mode that compromises their family life, health, and well-being. The person looking at his kitchen may feel the need to upgrade the granite, developing something of a countertop addiction and losing a sense of what he really wants to achieve in life.

He may also develop a tendency to overearn. As happiness from material stuff fades, people may work excessively to buy more things—even when they have more than enough money to live a comfortable life.

In a study, Hsee, University of Miami’s Jiao Zhang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Cindy F. Cai, and Booth PhD candidate Shirley Zhang asked people to listen to noises such as wood being sawed. This, in the research design, was equivalent to work. Study participants had to press a button to hear the sounds, which simulated doing work people don’t particularly enjoy. Study participants earned chocolates for the length of time they worked.

After this earning period, the participants entered a consumption period, during which they could eat all of the candy they’d just earned. They were told that they weren’t allowed to take any chocolates home, however— which created essentially a version of life where people can’t take earnings with them to the afterlife or pass them down to their children, Hsee says.

Many participants earned more chocolates than they could eat in the time allotted, particularly if they had been designated high earners and had to press the noise button just 20 times (as opposed to 120 times) to earn a piece. This group earned almost 11 chocolates on average but ate just four of them. After four, they’d generally eaten all they wanted, so they literally left the remaining chocolates on the table upon leaving.

“Using this paradigm, we found that individuals do overearn, even at the cost of happiness, and that overearning is a result of mindless accumulation—a tendency to work and earn until feeling tired rather than until having enough,” the researchers write. However, when participants were told that they could continue to work but would not earn more chocolates, they stopped sooner and felt happier, the research finds, suggesting that imposing an earning cap could reduce overworking and increase happiness. Hsee sees a parallel in real life, where productivity has enabled many people to work less for roughly equal pay, and yet they don’t take advantage of this and instead continue to work rather than relax.

Curiosity can also help, as people find pleasure in discovering enlightening detours and unexpected adventures. When they stop and ponder something new, or take on projects that increase their knowledge, this can facilitate greater happiness.

Hsee says that research with University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Bowen Ruan and Zoe Y. Lu reveals a nuance in the relationship between curiosity and happiness. In one study, people presented with new, interesting facts reported higher levels of satisfaction if they were asked questions but not immediately provided the answers. The process of discovery proved important.

Some lottery winners have learned that a jolt of happiness doesn’t necessarily last. In a particularly tragic case, Billie Bob Harrell Jr. won $31 million in the Texas lottery in 1997 but committed suicide two years later after saying that winning the lottery was “the worst thing that ever happened to me.”

While Harrell provides an extreme case study in the perils of sudden riches, researchers have been studying how long happiness sticks around—or evaporates—after a change such as a lottery win.

According to ideas42’s Raegan Tennant, a graduate of Chicago Booth’s PhD Program, and Booth’s Hsee, happiness will endure the closer it comes to helping a person meet an objective need or cross a defined threshold. Once the threshold is crossed, and the further away someone gets from that point, happiness due to sudden riches or another positive change is more likely to decay.

For several decades, psychologists have been studying hedonic durability, or how long happiness sticks around after a change. Tennant and Hsee investigated this by looking at how long happiness (or unhappiness) lasts in cases involving an objective variable—such as readable type size.

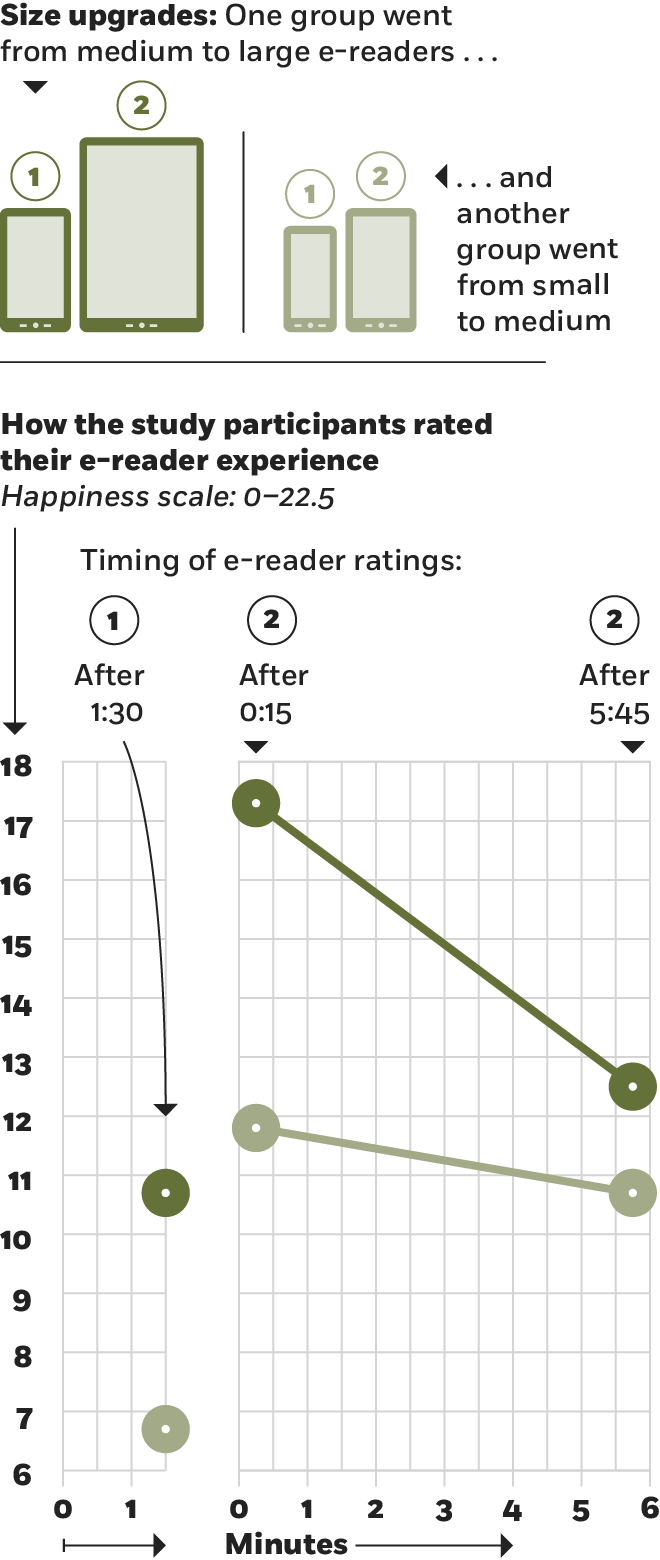

The researchers designed a study using various sizes of e-readers, including some with small screens on which the type was harder to read. In one experiment, they asked participants to read from two devices. Some read on a relatively large screen before switching to a medium-sized one. Others started on a medium-sized one and then moved to something smaller. They generally read for about two minutes on the first device and around 10 minutes on the second. At various points, the participants answered questions about what they were reading and how happy they were with the experience.

The researchers observed that everyone was initially unhappy moving to a smaller screen, but the unhappiness persisted only for people who were downgraded to the smallest screen. Similarly, in another experiment that involved people reading on devices of increasing size, the upgrade led to longer-lasting happiness only for people who started on the smallest screens.

These findings, Tennant and Hsee suggest, are not limited to screen sizes but are applicable to other domains as well. For example, someone moving from a tiny studio to a medium-sized apartment and someone moving from a large house to a huge mansion will both be happy initially, but over time, the happiness of the first person will stick and the happiness of the second person will fade. The reason is that an upgrade from a studio satisfies one’s inherent or basic needs for living, but an upgrade from a large house only satisfies a learned desire for bigger houses.

Raegan J. Tennant and Christopher K. Hsee, “Hedonic Non-durability Revisited: A Case for Two Types,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, December 2017.

Upgrades have their limits

The researchers find that people liked switching from a smaller e-reader to a larger one, but that happiness faded.

One curiosity experiment had two set-ups. In the first set-up, researchers told study participants that only humans and certain whales experience menopause. In the second, the researchers asked which animals the participants thought were affected by menopause, prompting the participants to think before receiving the answer. The people in the latter situation reported higher levels of satisfaction, apparently happiest when curiosity was stoked and soon resolved.

Hsee says he applies this finding in his teaching by asking students questions and giving them time to ponder before supplying answers. Children also benefit from learning to appreciate the power of curiosity, he says, suggesting individuals can put this finding to work for them, for example by reading questions about art before visiting a museum, or by reading questions about a new city before heading there. In this way, hedonomics teaches, tourists can extract happiness from a vacation to, say, Paris without having to visit more cities.

According to traditional economic theory, more choices are always preferable to less. A person faced with too many choices can always turn down the ones she doesn’t want. But this is a hot topic in decision-making research, as behavioral scientists have established that sometimes people prefer fewer choices. And hedonomics indicates that more choices may lower happiness and rev up the hedonic treadmill.

London Business School’s Simona Botti and Hsee ran a series of experi-ments in which they offered a number of people in a group more choices, some fewer, and some the chance to state which option they’d prefer. For example, in one experiment, they had people imagine having $10,000 to invest in a certificate of deposit and asked them to find the best CD available to them, any of which would pay between 3.01 percent and 4 percent. One group paid $7 for one set of three randomly generated options. A second group did the same, but was also given the option of spending another $7 for three more options, and so on, in a bid to find the best interest rate. A third group heard about both options, and then said which they’d prefer and predicted which would generate the best return.

The group told of both options preferred the freedom to have more choices, which they predicted would generate a better return. But in fact, people with more choices oversearched and ultimately earned less than people whose choices were restricted. There was a clear cost for more choice, $7, but people undervalued it. And the researchers find the same pattern in other experiments.

The amount of time people spend making purchasing decisions may lead to “faulty decisions and undesirable outcomes,” Botti and Hsee conclude. More choices led to worse outcomes, and by extension, to lower happiness. When it comes to choice—as industrial designer Peter Behrens said, and his protégé architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe often repeated—less is more.

The findings from hedonomics will have increasing importance as countries around the globe get richer. In many developing countries, the middle class is growing, which means millions more people will find themselves choosing between different types of televisions and countertops—and wines, purses, and jewelry—and looking for happiness in this newly acquired stuff.

In the US and other developed countries, where the middle class is shrinking, the lessons of hedonomics could be helpful for policy makers planning for demographic and workforce changes, Hsee says. The baby boom generation is aging out of the workforce, and up to half of today’s jobs may be automated in coming decades, according to a 2016 White House study. This transformation could leave a lot of people searching for work that might not exist, making potentially millions of people idle. Some economists, as well as business leaders, have expressed support for the idea of giving people a universal basic income—guaranteeing income of a certain amount to people who may find themselves unemployed and unemployable.

In a strict sense, this may not seem like a problem that can be addressed by hedonomics, which is about extracting the most happiness from a set amount of resources. A universal basic income could make people happier by making sure they can meet their basic needs.

But Hsee sees large numbers of idle people as a problem with political and social consequences—and essentially another problem that involves getting more happiness from one set of blocks. “You can make idle people happy by giving them a reason to ‘play with the existing blocks’ without accumulating more blocks,” he says, proposing the government consider programs that give people tasks to do, not unlike the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal era, which put people who were unemployed after the Great Depression back to work. Governments, he says, may need to find ways to engage people with activities.

Whatever the policy implications may be, and whatever form they could take, the research confirms the homespun wisdom that more money doesn’t necessarily buy more happiness. Instead, Hsee says, cherish what you have and make the best use of it.

Researchers put a twist on a classic experimental design.

How Some Experiments Use Emails to Control for Systemic Bias

The answer affects financial planners, caregivers, and many other surrogate decision makers.

Why We’re So Bad at Making Choices for Others

The “endowment effect” influences how people process information.

People Overreact to News about Stocks (and Other Things) They OwnYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.