One of data analysis’s most poetic features is that it often involves the aggregation of many individual observations to offer a broad view of some of the world’s biggest issues. And among the charts and graphics featured in the Chicago Booth ReviewSpring 2019 issue of , a few stand out from this perspective:

- An analysis of world governments’ programs to address climate change lets economists study the significance of one nation’s carbon tax—or measure the relative effectiveness of every known carbon tax across the world.

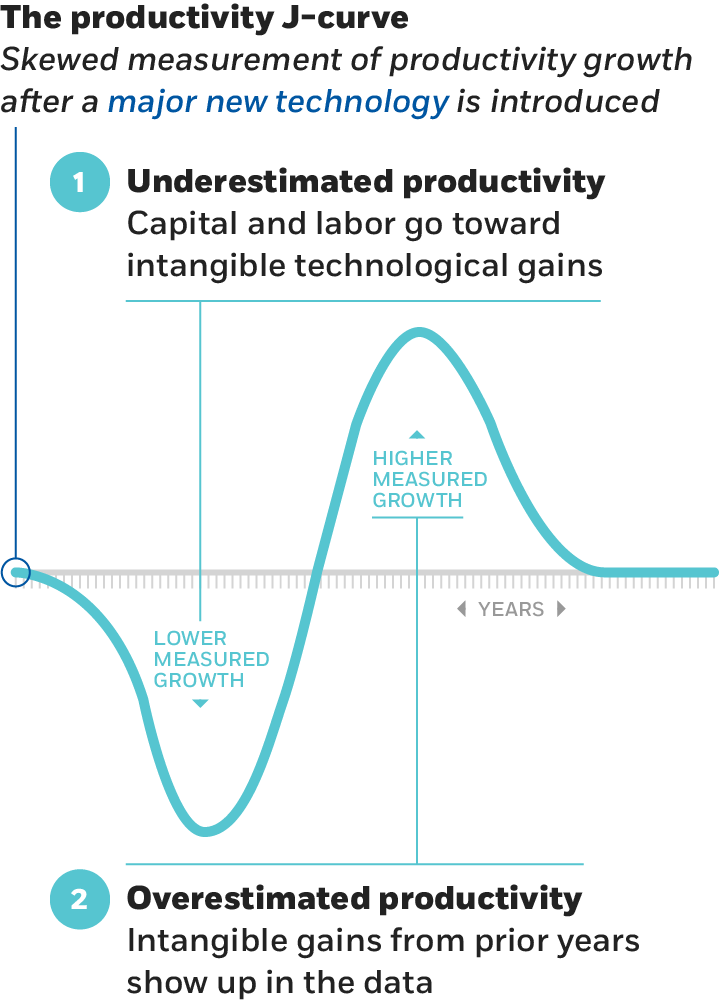

- An exploration of productivity data allows researchers not only to observe changes within local cities’ economies but also to zoom out and see economic ripples spread across the United States.

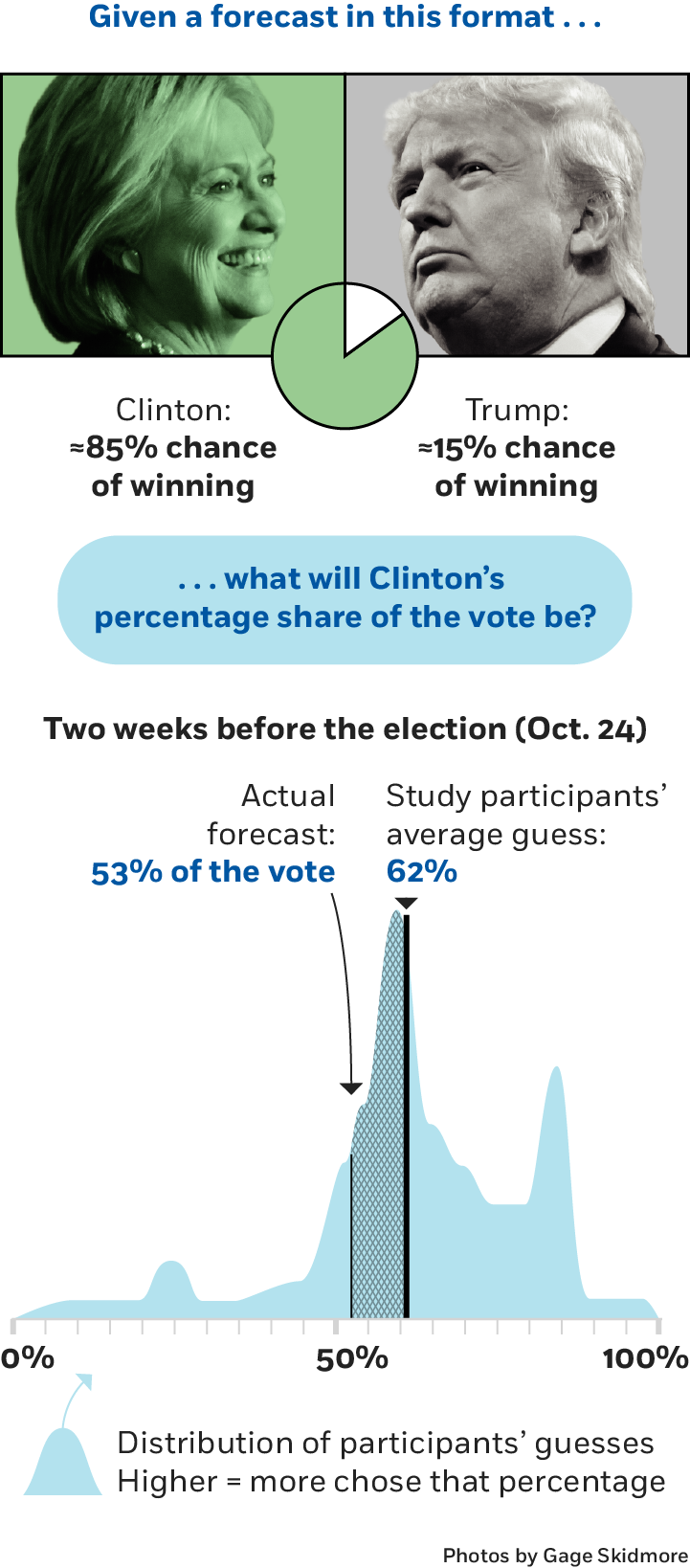

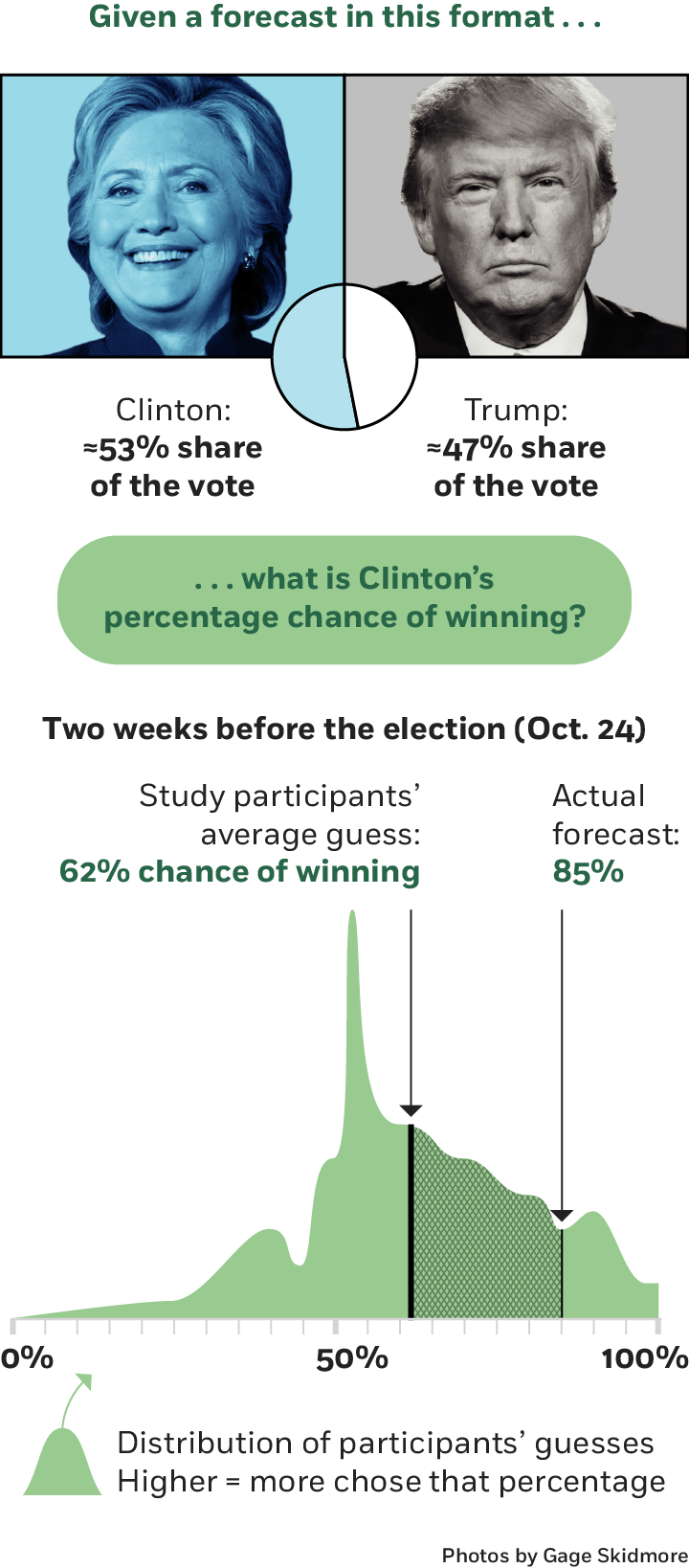

- A study of election forecasting tests individuals’ working knowledge of statistics—and provides insight into how pollsters might be influencing voters’ perceptions of political races nationwide.

Check out visualizations of these and other data below—and peruse CBR’s spring issue for more research on topics of global, national, and local importance to business leaders and policy makers.

According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, carbon stored in the Earth’s atmosphere is at its highest level in 800,000 years. The effects of the warming atmosphere will be felt more quickly than anticipated, a United Nations scientific panel concluded last October, saying that without a global carbon tax to nudge individuals and companies into action, any temperature target will be exponentially harder to meet. Twenty-six countries and provinces have implemented some form of carbon tax, according to the World Bank, and there are another 25 emissions-trading systems. But these efforts address only a small fraction of global carbon emissions.