The Equation: Are Supply Chains Holding Back Productivity Growth?

If some suppliers are innovating at a much faster pace than others, it can hinder an industry’s growth.

The Equation: Are Supply Chains Holding Back Productivity Growth?

Ryan Todd

At a conference held by the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics, University of Chicago’s Alessandra Voena moderated a discussion with Harvard’s Claudia Goldin and Chicago Booth’s Veronica Guerrieri about the challenges faced and progress made by women in economics, a field where women are one-third of undergraduate students yet only 14 percent of full professors in PhD-granting departments. This excerpt from their discussion has been edited for space.

Goldin: I call this the demography of economics: how male and female economists are “born” when they are undergrads, and then become graduate students, and persist in one field or another in economics. I want to replace the pipeline metaphor because by thinking of this as a process of survival, we can better think about treatments and interventions. And by thinking about it as this process, as a real life cycle, we can also consider other aspects of our own life cycles, such as family formation.

The largest relative “mortality” of women economists occurs at the very start of the process—as undergraduates. Among the top 100 US universities that train most of our graduate students from US institutions, there are more than two undergraduate men majoring in economics for every one woman. But the ratio of males to females who earn bachelor’s degrees from these institutions is actually below 1:1, so we lose a lot of women at the start; when they are undergraduates, they don’t major in economics to the same degree males do.

There are two males for every female PhD, three males for every female assistant professor and associate professor, and six males for every female full professor. The fraction female doesn’t change much from economics undergraduate degrees until the tenure ranks. The fraction female among full professors has more than doubled, from 6 percent to 14 percent, across a 20-year period. But for undergraduates, the ratio of males to females really hasn’t budged much.

What about treatments or interventions to reduce this mortality rate? The issues will vary by demographic stage in economics—that is, by the phase in the academic life cycle. And treatments and interventions that we can think about will also vary.

Encouraging undergraduate women to major in economics is about making economics about real issues for them before they enter their universities and colleges—before they have decided that they don’t want to major in economics to the same degree as men do, before they really know anything about the subject. We are losing them because they don’t understand what economics is.

Among graduate students, there are issues concerning mentoring and advising. There are issues concerning the seminar culture. Among assistant professors, there are issues concerning tenure and publishing, credit for coauthorship, perhaps problems in refereeing and bias in the tenure process. And at all ranks, there’s the problem of the competing clocks, tenure and biological.

Why does any of this matter? One reason is that male and female economists actually appear to have different interests, as shown in their fields of specialty. Using National Bureau of Economic Research information about program groups, I coded up the fraction female among research associates and faculty research fellows, who are a bit younger. I also coded up all of the Harvard PhDs who have been on the market for the past couple of years. Relative to men, these women have gravitated to fields such as labor, education, health, and industrial organization, and less so to macro, econometrics, and finance. Thus, knowledge creation and the world of ideas with too few women will be very different. We really don’t know that much about how the world of ideas differs by gender within these fields.

Guerrieri: On the productivity side, we may just miss some talent because there are talented women who do not have an environment where they feel comfortable and can reach their potential.

Voena: The debate on the subject of female representation is now at the forefront of many discussions in this profession. So progress is being made. I think it’s important to know that our profession is improving, but challenges remain. What have you observed over the course of your career in terms of what the experience for representation and equal treatment of women in the profession has been?

Guerrieri: I did my undergrad in Italy, so my experience in the economics profession in the United States goes back to my PhD, which I started doing at MIT in 2001. At the time, women were around a third of the class. It looks like this was pretty representative of the average in the top US institutions. And it looks like participation in the economics profession at the PhD level is still something that we have not made much progress on.

Where it looks like we are making some progress, from the numbers, is in how far women are going in their professional careers. These numbers have been improving over time. I’ve seen that in my experience as well. There are more women now than when I started in the profession, but we’re still lagging behind.

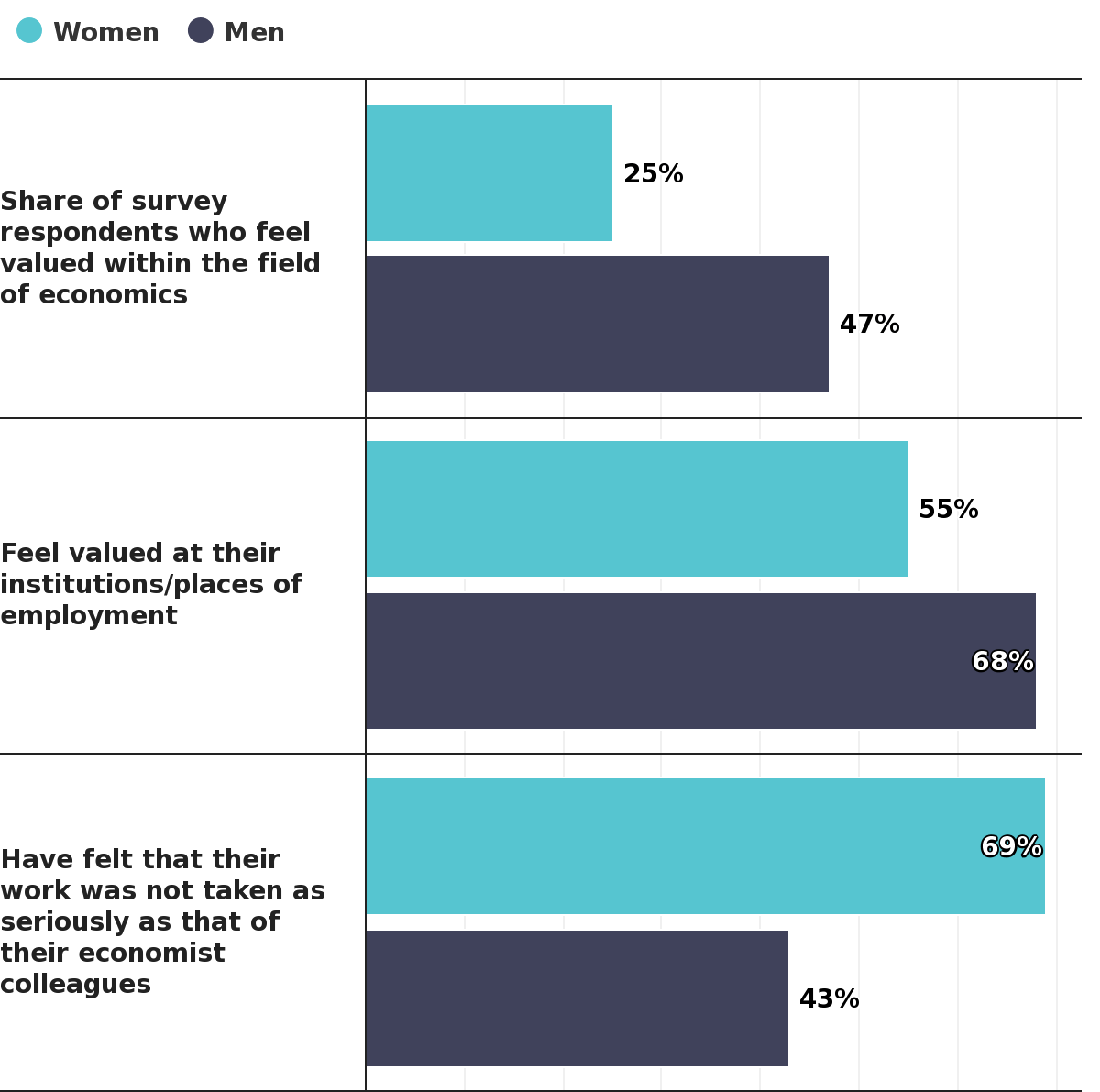

An American Economic Association survey, which drew 9,000 responses from current and former members, indicates there is widespread discrimination in the profession. Read more

A lot of junior colleagues have raised the issue of lack of mentorship or role models in macroeconomics, so we decided—Alessandra Fogli, who is at the Minneapolis Fed; Marina Azzimonti, who is at Stony Brook; and myself—to organize a conference last year for women in macro. This year, we are going to replicate that here in Chicago. At the beginning, I was a little suspicious because you don’t want to seclude or segregate women even more. But it was a great opportunity for generations of women to interact and network, and for younger women to ask advice about how to succeed in the field and to feel less alone in the profession.

The culture in the seminar was pretty different from a typical macro seminar. It wasn’t less aggressive in content, because people were criticizing the work and there were discussions, but the style was different. I believe the profession would benefit from having a larger share of women and a change in the culture overall.

Goldin: When I first began, there weren’t many women in the field, even fewer in my own field of economic history, which lagged tremendously in attracting women, for reasons that I don’t know.

Also, for the longest time, economist women didn’t have a lot of kids. You would never see a pregnant assistant professor. Now there are babies all over the place, and it’s a wonderful thing.

Voena: Many features of modern academia were shaped during times in which women were unlikely to work. Do you think that this historical heritage has created structural features in academia that might affect female representation and equal treatment? And might this affect economics in some practical way as opposed to other disciplines?

Goldin: Almost all professions are up-or-out. If you don’t go up, you sort of know you’re out. But we then get these competing clocks, which are even worse in academia now, particularly in economics. When I was a graduate student, you went to graduate school straight out of being an undergraduate. Now people get their bachelor’s degree somewhat later. They take a couple of years out to be a research assistant for someone. They then go and get their PhD, which no longer takes four years. So these tenure and biological clocks are competing even more now than ever.

And we inherit the social norms of our society. Many women who are on the same track as the person they love and who want to have a family will often step back. And when they step back in academia, they become adjuncts.

Guerrieri: Clearly, the dual clock is one of the main issues for women. Not the only one, but definitely one. Ideally, our objective is to arrive at a situation where, in all professions, there is total equality between men and women, and everybody takes some of the burden of family work. I don’t think we are there yet.

This raises an issue about how we treat paternity and maternity leave. In order to aim to arrive at this ideal where everybody does the same amount, in both the family and the work, there needs to be equality in the treatment of paternity and maternity leave. But this often, unfortunately, means that colleagues who have their wives at home with the kids are disproportionately advantaged relative to the female colleagues who need to care for their babies as well as write papers. You don’t want to give the wrong incentive to men, not to take care of the kids. But there is a tension there, and it’s not easy to resolve.

These issues may also be a little worse in economics. In many disciplines, all the more so in the sciences, people have one or two postdocs, maybe even three. By the time they become an assistant professor, they will probably have kids. The tenure comes much later. Whereas in economics, there are postdocs, but they’re typically just one year.

Voena: What type of research might be needed? What are the natural, safe sources of funding for this type of research?

Guerrieri: I have seen a proliferation of research on the issue. I see some advantage to more work being put into policy proposals that try to improve the situation. All university departments are much more sensitive to the topic. I think that funding should not be a problem, and there should be a lot of attention to this type of research.

Goldin: I’ve been running a randomized controlled trial concerning how to get more women to major in economics as undergraduates. How can we convey what economics is? There is some problem in how what we do is being conveyed to the populace.

What we’ve discovered is that women as undergraduates observe the grade that they get in their principles [of economics] course. If they get below an A-, women are less likely to pursue economics, and the fraction who eventually major in economics drops. The guys, you could hit them over the head with a baseball bat, and they would still stay in economics. So a treatment that we’ve tried in our trial is when undergraduate women get below an A- in economics and they’re really interested in it, you support them and tell them that they will do better and that we will help them. This is working at various institutions.

Claudia Goldin is the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard. Veronica Guerrieri is the Ronald E. Tarrson Professor of Economics at Chicago Booth. Alessandra Voena is associate professor in economics and the College at the University of Chicago.

If some suppliers are innovating at a much faster pace than others, it can hinder an industry’s growth.

The Equation: Are Supply Chains Holding Back Productivity Growth?

A Chinese pandemic-era program involving targeted digital coupons generated almost three times as much buying as the coupons cost.

For Economic Stimulus, Try Giving People Coupons, Not Cash

The growth of privately held businesses has some regulators and policy makers pondering whether to push for more financial transparency.

Is the US Economy ‘Going Dark’?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.