To Keep Students Focused, Try Paying Their Parents

A study of subsidized training programs and incentives explored who should be included.

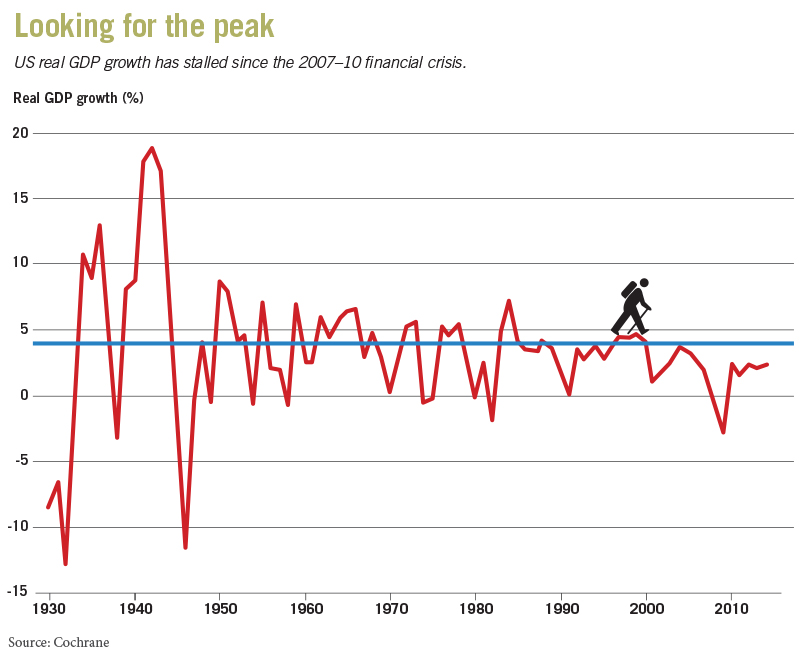

To Keep Students Focused, Try Paying Their ParentsTimothy Noah from Politico called to ask if I thought 4 percent US economic growth for a decade is possible. In particular, he asked me if I agreed with other economists, later identified in the story, who commented that it has never happened in the United States, so presumably it is impossible.

Noah writes:

While 4 percent growth can last for years at the state level, it has never been anything approaching the norm in US economic history, even during the boom years that followed World War II. “I can go back 200 years,” said Claudia Goldin, an economic historian at Harvard, “and not get anything like this in a sustained manner.” These comments by Goldin and other economists prompted me to look up the facts, presented in the accompanying chart. Judge for yourself how far out of historical norms 4 percent growth is.

By my eye, avoiding a recession and returning to pre-2000 norms gets you pretty close. A strong pro-growth policy tilt—cleaning up the obvious tax, legal, and regulatory constraints drowning our Republic of Paperwork (as Mark Steyn put it at National Review)—only needs to add less than a percent on top of that. Four percent might be too low a target!

Note that the question asks about real GDP, not per-capita GDP. The latter is a better measure, but the question is whether we can get 4 percent real GDP. Adding capitas counts. Regularizing the 11 million people who are here and letting in people who want to come and work and pay taxes counts toward total GDP growth, even if it did not improve per-capita growth.

You may argue with the wisdom of a freer immigration policy, but the point here is about numbers.

This is not a serious, nor a scientific, answer to the question of whether 4 percent growth is possible. The serious answer looks hard at demographics and productivity, estimates how far below the free-market-nirvana level of GDP we are, and estimates how much faster free-market nirvana GDP could grow. If you think that sand in the gears or inadequate infrastructure or not enough stimulus means we’re 20 percent below potential, and potential can grow 2 percent per year, 4 percent growth for a decade follows.

An optimist might look beyond 4 percent. If the past did not often grow that fast, this is largely irrelevant, since the US has never experienced free-market nirvana.

Historical trends can be misleading. If you were to look in 1990 at historical Chinese GDP plots to assess whether it is possible for China to grow as it has for the last 25 years, you’d say such growth is outlandishly impossible. Conversely, if you were to look at US data until 1999, you’d say our lost decade of 2 percent growth could never happen.

But, having asked the question of whether 4 percent is outside of all US historical experience, at least it’s interesting to know the answer. No.

A few people have asked me, “Why do so many of your colleagues disagree?” It’s a question I hate. It’s hard enough to understand the economy; I don’t pretend to understand how others respond to media inquiries. And I don’t like the invitation to squabble in public. It has taken me some time to reflect on it, though, and I think I have a useful answer. I think we actually agree.

As I read through the many economists’ quotes in the media, I don’t think there is in fact substantial disagreement on the economic question—Is it economically possible for the US to grow at 4 percent for a decade or more? Their caution is political. They don’t think that any of the announced presidential candidates (at least with a prayer of being elected) will advocate, let alone get enacted, a set of policies sufficiently radical to raise growth that much.

This is a sensible position. When I address the question “Is 4 percent growth for a decade economically possible?” I do not impose my amateur reading of political constraints. My answer considers whether the most extreme pro-growth policies would yield at least that result. A short list of growth-raising policies:

And so on. Essentially, every single action and policy is reoriented toward growth.

More people return to work, i.e., labor-force participation increases. We get a spurt of productivity growth from greater efficiency without needing big innovations and investments. And then innovation and new businesses, investment, and technology kick in.

There would be a lot of lawyer, accountant, lobbyist, compliance officer, and regulator unemployment. Well, Uber needs drivers.

I think my fellow economists might agree that 4 percent growth for a decade is possible with such a program. In fact, we can likely get to 4 percent with much less than all of these policies. They might complain about inequality or other objectives. But most of all, they might say it’s unlikely that the new president and US Congress will enact such a program.

That’s a reasonable view. But, dear colleagues, they asked us about economic possibility, not our guess about political probability. It would be better to say: “Sure, 4 percent growth is economically possible. But I don’t think any politician will advocate the policies necessary to produce it.” If we were to say that more often, we just might get such policies and politicians.

You never know what’s “politically feasible.” In 1955, civil rights were “politically infeasible.” In 2005, gay marriage was “politically infeasible.” Politics sticks in the mud for 100 years and then changes faster than we can imagine.

I think there actually are quite a few politicians who would do some of the radical things that need to be done. They need to hear from us that it could work, as a matter of economics. Let them handle the politics.

We will soon see a first test: can any candidate show up in Iowa and say, “Ladies and gentlemen, government-subsidized corn ethanol is a rotten idea”? The campaign season is young. Let’s not prejudge them.

Growth is just too important to give up on so easily. Sclerotic growth is the economic issue of our time, and economists should be cheering any policy agenda focused on growth. If you think the policies needed to give us growth are hard, and out of the current political mainstream, that’s ever more reason to keep reminding people that growth is possible and needs big changes—not to confuse, “It’s unlikely they’ll do it,” with, “It’s economically impossible.”

John H. Cochrane is distinguished senior fellow at Chicago Booth.

A study of subsidized training programs and incentives explored who should be included.

To Keep Students Focused, Try Paying Their Parents

Two economists with very different views on inequality discuss the magnitude of the problem.

Is Wealth Inequality Overstated?

Research is examining how forces outside the workplace affect inequalities in professional outcomes.

Does the Gender Gap Begin at Home?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.