How much more economic growth could the US achieve with better policies? The issue has enlivened the presidential campaign.

- By

- February 26, 2016

- CBR - Economics

How much more economic growth could the US achieve with better policies? The issue has enlivened the presidential campaign.

How much more economic growth could the US achieve with better policies? The issue has enlivened the presidential campaign, with governor Jeb Bush arguing for a 4 percent growth goal, and antagonists quickly shooting that down as unachievable. But what is achievable, really?

Monetary and fiscal stimulus programs only boost the economy temporarily. Nothing but “structural” policies that permanently increase the efficiency of the economy can hope to have a lasting impact.

Now, there are many criticisms of the US’s economic inefficiency, especially that taxes and regulation are too onerous and unpredictable. But how much can raising economic efficiency really raise economic growth?

Economics used to make a sharp distinction between policies that can permanently raise the growth rate of output and incomes, and policies that only raise the level of output and incomes, without affecting the long-term growth rate. A lot of free-market policy prescriptions that target inefficiency are often swept into the latter group. After a period of adjustment—you do grow while you move to a higher level—they won’t ultimately speed up the economy’s growth at all. Clearly, it’s better to permanently raise the growth rate. A permanent rise in growth would soon overtake one-shot level increases, and in fact we could soon tolerate and outgrow existing inefficiencies including regulation and taxes.

However, the distinction between level and growth policies is no longer so clear-cut: growth effects are smaller and less permanent than you may have thought, and level effects are bigger and longer lasting than you may have thought.

Consider China.

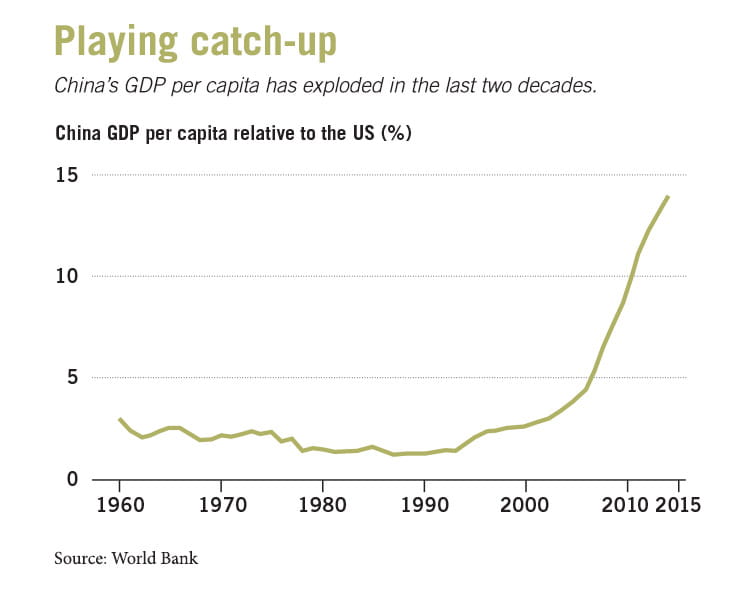

China removed exactly the sort of “level” or “inefficiency” economic distortions that free-market economists such as myself (and Adam Smith) recommend. What happened? Here is a plot of China’s per capita GDP, relative to the US’s (see “Playing catch-up”). In case you’ve been sleeping under a rock somewhere, China took off.

Now, in the “growth” versus “level” dichotomy, China experienced a pure level effect. Its GDP increased by removing barriers to “short-term” efficiency, basically just getting out of the way and letting people start businesses, not by any of the “long-term” growth changes, such as more research and development, basic scientific research, or new productivity-raising ideas, stressed by the first-generation growth theories.

But China reminds us that this “temporary,” “short-term” “level effect” or “catch-up” growth can last for decades. And it can dramatically increase people’s well-being. From 2000 to 2014, China’s GDP per capita grew by a factor of seven, from $955 per person to $7,594 per person, which is a 14.8 percent annual compound growth rate. And it is still just 15 percent of the US level of GDP per person. There is a lot of “growth” left in this “level” effect!

Lots of people use the word “growth” to describe what happened to China and would not belittle policies that could make the same thing happen in the US.

But can liberalization policies have the same effect here? The US is a “technological frontier” country. China can copy what we’re doing. There is nobody for the US to copy. Big increases in levels, which look like growth for a while, are over for us.

But are they? We know how much better China’s economy can be because we see the US. We know how much better North Korea’s could be because we see South Korea. How much better could the US’s be, really, if it removed all distortions to a free market?

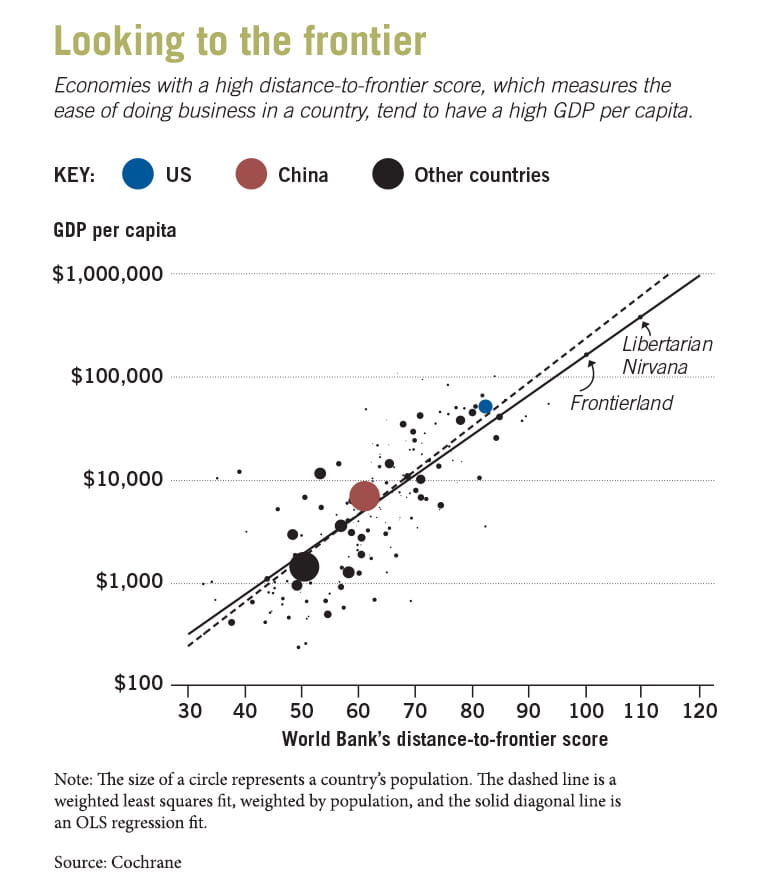

To think about this issue, I made a graph of GDP per capita versus the World Bank’s distance-to-frontier score (see “Looking to the frontier”). The frontier is, according to the website, “the best performance observed on each of the [numerous] indicators across all economies in the Doing Business sample since 2005.” The individual indicators are things such as starting a business, dealing with construction permits, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, and trading across borders.

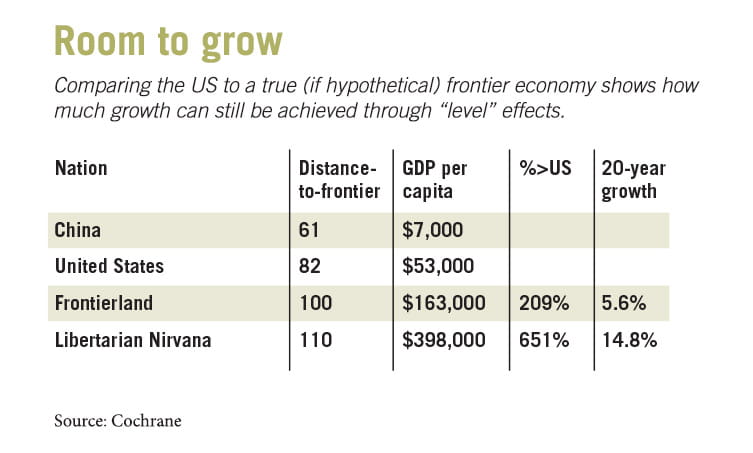

The US has a per capita GDP of $53,000 per year and a distance score of 82. China is at $7,000 GDP per capita, with a distance score of 61.

Evidently, the distance-to-frontier score is highly correlated with GDP per capita. The score tracks enormous variation in performance, from the abject poverty of $1,000 per year, through the US, and beyond.

Too much growth commentary, I think, confounds “frontier” with “perfect.” The US has good institutions, but not perfect ones. It takes forever to get a building permit in Libya. It takes two years or more to get one in Palo Alto, California. It could take 10 minutes. The US is not completely uncorrupt. The tax code is not perfect. Property rights in the US are not ironclad. A lawsuit might take 10 years in Egypt, but it still could take three years here. (Disclaimer: these estimated delays are all made up.) And so forth.

So, the big question is, just how much greater “level”—and how much China-like “growth” on the way—could the US achieve by improving its good but imperfect institutions?

The distance-to-frontier score is relative to the best observed performance on each dimension in the World Bank sample. So a score of 100 is certainly possible. I labeled a 100 score by a hypothetical nation, Frontierland, in the graph.

But perhaps we can do even better. Even the best nations in the world are not perfect. Let’s call a nation with the best possible institutions Libertarian Nirvana. How good could it be? If the US is currently 82, and the union of best current practices 100, let’s consider the implications of a 110 guesstimate.

The table (see “Room to grow,” left) shows China and the US along with my hypothetical new nations. Frontierland generates $163,000 of GDP per capita, 209 percent better than the US. If it takes 20 years to adjust, that means 5.6 percent per year compound growth. Libertarian Nirvana generates $398,000 of GDP per capita, 651 percent better than the US, a level effect that, if achieved in 20 years, generates 14.8 percent compound annual growth along the way.

These numbers seem big, but there are no black boxes here. I’m just fitting the line shown in the graph. And China just did achieve nearly 20 years of 14 percent growth, and a 700 percent improvement. If you had not known the US was there, it would have seemed an unrealistic hope, ex-ante.

It is surprising that bad policies, bad institutions, and bad ease of doing business can do quite so much damage. But the evidence—especially from basically controlled experiments comparing North and South Korea or East and West Germany—is pretty strong.

The logical conclusion is that improvements to institutions and greater ease of doing business must be able to do equivalent amounts of good.

This analysis is admittedly simplistic. Growth theory does distinguish between ideas produced by the frontier country, which are harder to improve, and “misallocation” and the development of more efficiency using existing ideas. As traditional macroeconomics thinks about aggregate demand easily raising GDP until we run into aggregate supply, there is a point of superb efficiency beyond which you can’t go without more ideas. I don’t know where that point is. But uniting the existing best practices around the world in Frontierland is surely a lower bound, and an extra 10 percent doesn’t seem horribly implausible.

So I conclude optimistically. The US is not doomed to a new normal of terribly slow growth, to battle over redistribution of a sclerotic pie. Simple Adam Smith efficiencies, applied to the US, could give the country something like the growth experience of China. And if that’s only a “level” effect, well, it’s still pretty good.

John H. Cochrane is distinguished senior fellow at Chicago Booth and a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Bottlenecks can form when industries innovate at different paces.

Lopsided Innovation Causes Productivity Slowdowns

The decisions of companies, governments, and educators will help to shape the ultimate outcomes of the A.I. revolution.

A.I. Is Going to Disrupt the Labor Market. It Doesn’t Have to Destroy It.

Chicago Booth’s Chang-Tai Hsieh discusses China’s economy with the Capitalisn’t podcast.

Capitalisn’t: The End of China’s Miracle?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.