Financial success is only part of what motivates small-business owners.

- By

- March 04, 2016

- CBR - Economics

Financial success is only part of what motivates small-business owners.

Long before Apple was a corporate behemoth, it was a small venture that had been started in a garage in Los Altos, California. The US government would like to see lots more similar success stories. It offers a variety of incentives to encourage small companies to launch, innovate, and grow.

But research suggests that some of these incentives may be based on a misperception of what small-business owners value and want.

Independent businesses with fewer than 500 employees are a huge part of the US economy. They create almost half of US private-sector jobs, and 64 percent of net new jobs. According to census data, the United States has 6.2 million small businesses with a single physical location, compared with 1.2 million companies with at least 500 employees. Some industries are run almost entirely by small-business owners—including florists, dentists, and plumbers.

The US offers all sorts of incentives for these business owners. The 2010 Affordable Care Act, for example, exempts businesses with fewer than 50 employees from having to provide mandatory health insurance.

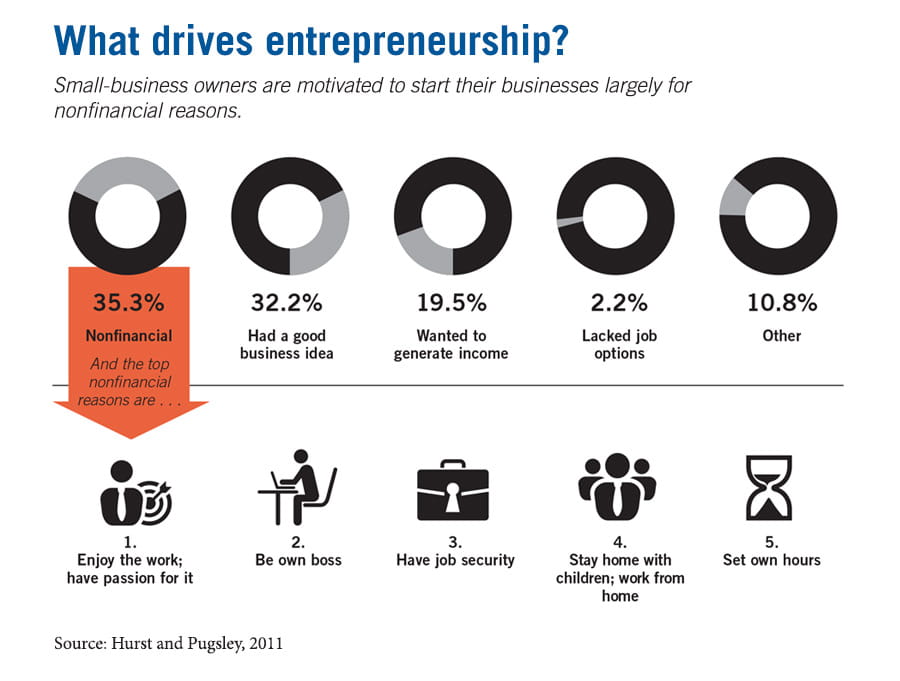

But Chicago Booth’s Erik Hurst and Benjamin W. Pugsley at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York point out that, according to their past research, financial success is only part of what motivates small-business owners, who generally earn less than they could in corporate jobs. As the researchers documented in 2011, almost 50 percent of business owners at the start were influenced by factors other than money, such as wanting to keep flexible hours, be one’s own boss, and pursue a passion.

Moreover, many small businesses remained small, despite incentives that encouraged them to ramp up. “When asked about their ideal firm size, the median response of new business owners is that they desire their business to only have at most a few employees,” the researchers write.

To assess the impact of these nonmonetary benefits, Hurst and Pugsley created a new model of the small-business sector, looking for what causes people to launch companies. Their model predicts that people who value nonmonetary benefits will concentrate in industries where companies don’t naturally scale up, and where being small could even be a competitive advantage.

The model also predicts a correlation between small-business ownership and wealth, suggesting that “owning a business is a relative luxury good,” according to the researchers.

Perhaps most controversially, the researchers find that small-business subsidies are regressive. More small-business owners are wealthy than they are poor, they say, so “the subsidy on small-business ownership just transfers resources to the wealthy from the poor.”

Hurst and Pugsley also don’t agree with the widespread notion that small businesses would all generally grow faster if they weren’t cash strapped and burdened by government regulations. “This is likely true for some small businesses,” they write, but not for those whose owners are motivated by nonmonetary factors.

Policymakers need to understand better what small-business owners value, the researchers conclude. Many mistakenly believe that small businesses are the engines of economic growth—and they write policies that may not actually further economic growth. Hurst and Pugsley suggest that subsidies may be less distortionary, and more effective, “if they were targeted at growth and innovation as opposed to being mostly linked to firm size.”

The researchers say they don’t know of any empirical research that weighs the costs and benefits of small-business subsidies and concludes there’s a net benefit. “Addressing this question seems like a very important area for future research,” they suggest.

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan describes the task ahead for the US Federal Reserve.

Why a Soft Landing Is So Hard

Research examines two different types of labor-market policy designed to help displaced workers pivot to new jobs.

How Should We Help Workers Exposed to Offshoring?

Is inefficiency inherent in the matching of students and colleges?

How Colleges Can Make the Admissions Process Easier for Students, and ThemselvesYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.