Banks don’t always request financial statements from a borrower—whether they do depends on their relationship with a borrower and a borrower’s credit risk.

- By

- June 20, 2014

- CBR - Accounting

Banks don’t always request financial statements from a borrower—whether they do depends on their relationship with a borrower and a borrower’s credit risk.

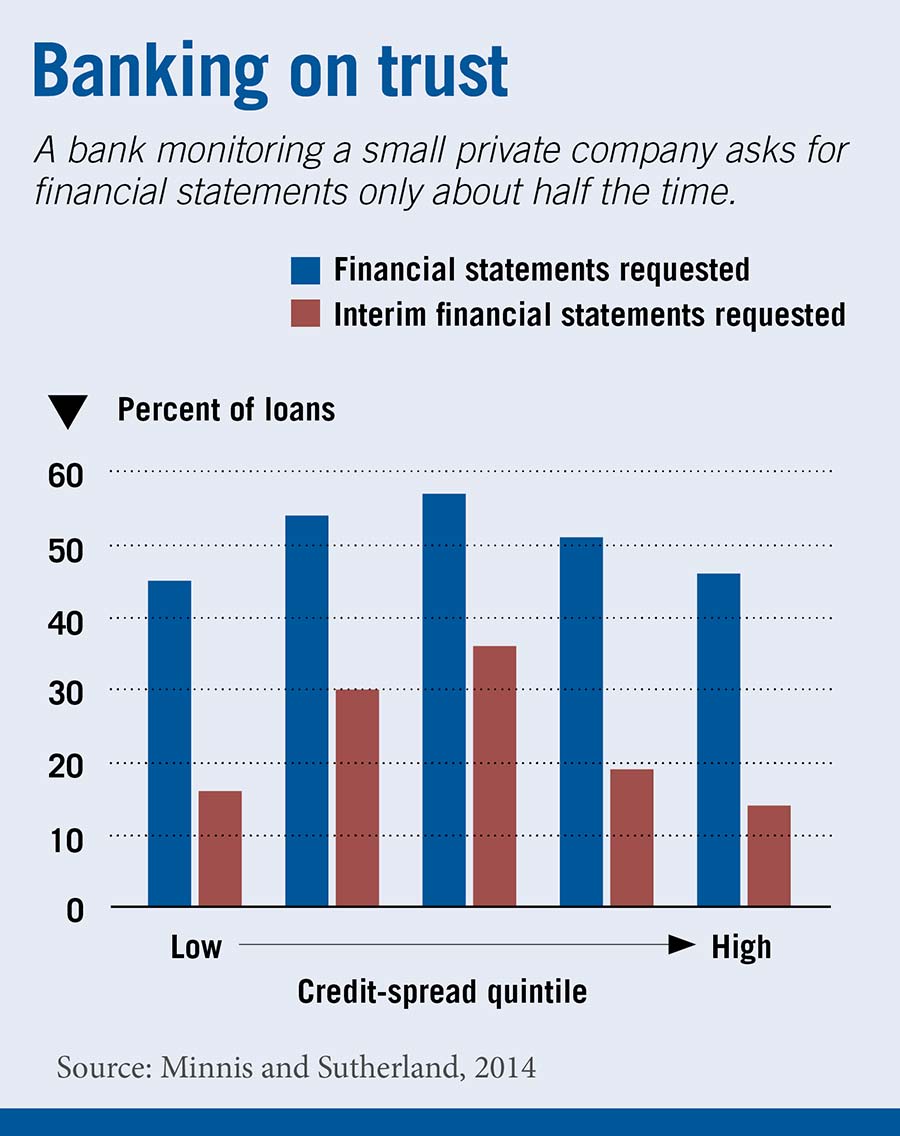

After a bank loans money to a private company, one that isn't required by regulation to produce financial statements, how does the bank keep tabs on the company's finances? About half the time, a bank monitors a small private company by requesting financial statements, and in other cases it asks for tax returns or proof of creditworthiness. But often the bank doesn't require any financial reporting—faith and collateral are sufficient.

The best reporting system would combine rules-based and principles-based approaches.

A Guide for More Accurate, Transparent Financial Reporting

Compensation regulations for bankers' in the UK and EU have helped curb risk, but they've come with some unintended consequences.

Does Limiting Bankers’ Pay Work?

Researchers find that financial reporting incentives influence accounting quality, despite the many potential benefits from international accounting harmonization under IFRS.

Why It Doesn’t Make Sense to Force Financial Reporting ReformUS regulations require financial reporting, but only for publicly traded companies. Private companies have an incentive to eliminate costly reporting that they believe is unnecessary—and the cost burden is particularly high for small companies. Chicago Booth Assistant Professor Michael Minnis and Booth PhD candidate Andrew Sutherland wanted to know how banks and borrowers interact when financial reporting is not mandated by regulation, and monitoring is based on a cost-benefit negotiation between bank and borrower.

It's difficult to find out because financial data is not publicly available for private firms the way it is for companies listed on a stock exchange. Most private firms do not have extensively public reporting requirements. Therefore, they are not required to follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), produce audited financial statements, or report their results publicly. As a result, researchers are often unable to readily obtain financial data for private companies of all sizes, including pre-IPO companies, the new "emerging growth company" category created by the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, and companies owned by private-equity firms.

If firms don't have to produce financial statements, many choose not to because of the associated cost. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF), and National Association of State Boards of Accountancy created the Blue-Ribbon Panel on Standard Setting for Private Companies, driven by concerns over the complexity of GAAP. The Private Company Council, formed under the auspices of FAF, is also recommending exceptions to GAAP for private firms. The Financial Accounting Standards Board recently endorsed two such exceptions and plans to propose more.

Minnis and Sutherland overcome the usual dearth of verifiable private-company data by mining a proprietary database called Monitor, developed by Sageworks, Inc. The software helps banks monitor loans in their portfolio. Banks use Monitor to schedule future document-request dates, and Monitor includes a description of the document requested and its frequency (e.g., annually, quarterly, monthly). The US Department of the Treasury's Office of the Comptroller of the Currency requires nationally chartered banks to create policies, procedures, and data that form "the foundation for credit risk measurement, monitoring, and reporting" and support decision-making. Because of this regulatory requirement, bankers routinely enter all the monitoring items in loan agreements.

The researchers find that a bank's decision about whether to request a borrower's financial statements depends on five things: the bank-borrower relationship, the loan's credit spread (the difference between the interest rate on the loan and the prime rate), the presence of collateral, the availability of alternative information sources, and other loan contract terms.

Reputation and relationship play a unique role in this decision. As a bank's relationship with a borrower grows longer, bankers request financial statements less often. However, when that same relationship grows deeper—meaning the borrower takes out more loans—bankers begin to request financial statements more often.

Banks monitor borrowers after making loans in order to protect their rights to collateral and cash flow in the event of borrower default. Loan terms must use metrics that are easy to get and verify, and financial-statement data includes such metrics. This information can help borrowers obtain loans on better terms relative to not reporting anything back to their bank, which supports the borrowers' ongoing creditworthiness and the value of their collateral.

When collateral is involved, financial statements are particularly useful when shared frequently. Collateral gives a lender good reason to closely monitor financial statements to make sure that collateral is intact, and hasn't been transferred to an executive or related party.

Borrowers may prefer providing tax returns instead of financial statements, given that tax returns provide data that can overlap with that provided by financial statements. Plus firms have tax returns already available since they are required to produce tax returns by the IRS annually. That potentially makes tax returns cost-beneficial to provide.

Some lenders may find that tax returns may not be as informative as financial statements, as they provide similar, but not identical, financial information. But other lenders may consider tax returns fine substitutes, or perhaps even complements, to financial statements.

Banks, therefore, sometimes ask for both. That happens "when the relationship is shorter or more complex, when the amount of non-financial information collected by the bank is higher, or when the borrower has a middle-tier credit risk," the researchers write. And while tax returns are readily available and prepared in a consistent manner enforced by the IRS, they're prepared according to tax rules that differ from accounting rules. When banks are concerned about information asymmetry—when the borrower has information relevant to the lending decision and the bank does not—tax returns level the playing field.

Minnis and Sutherland cite a 1991 paper by Chicago Booth Professor Douglas W. Diamond, which predicts that banks monitor companies with middle-tier credit risk more intensively than those with either high or low credit risk. Low-risk borrowers worry about their reputations, so they stop themselves from engaging in risky financial behavior such as overleverage or excessive capital expenditures, Diamond argues. Since these borrowers self-monitor, the benefit of bank monitoring is reduced. High-risk borrowers, on the other hand, have little reputation to lose and may take more chances. As monitoring doesn't change these borrowers' behavior, lenders rely on credit rationing and higher interest rates to limit default exposure.

Minnis and Sutherland, in their empirical study, confirm Diamond's hypothesis: they find that banks tend to request financial statements equally often for companies whose credit risk is in the top and bottom quintiles, as measured by credit spread. However, their propensity to request financial statements is about 25% higher for companies whose risk is in the middle quintile. The chart highlights this "inverse U-shape" relation.

A few caveats: the researchers' dataset represents loans made to small private businesses, and the average loan size in the sample is $242,835. Information supplied by the Monitor software vendor suggests that the sample covers banks of all size, operating in wide-ranging geographic locations and product markets. The researchers had limited information about the individual banks or borrowers.

The financial data, whether found in financial statements, tax returns, or other sources, are used to monitor loans already made, not to make credit decisions. The researchers don't examine which sources of monitoring data lead to fewer or smaller loan losses. Finally, the time period of the study is largely limited to loans that originated between 2009 and 2012, and the findings may not apply to other time periods.

Investment manager Jim Chanos discusses short selling’s role in financial markets.

Capitalisn’t: Is Short Selling Dead?

The growth of privately held businesses has some regulators and policy makers pondering whether to push for more financial transparency.

Is the US Economy ‘Going Dark’?

Big funds lead to big asset managers—and big has performance issues.

In Active Mutual Funds, Bigger Still Isn’t BetterYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.