An excerpt from Atif Mian and Amir Sufi's book on the Great Recession

- By

- July 01, 2014

- CBR - Economics

An excerpt from Atif Mian and Amir Sufi's book on the Great Recession

All of us face unforeseen threats that can alter our lives: an unexpected illness, a horrible storm, a fire. We understand we need to be protected against such events, and we buy insurance to be compensated when these events happen. This is one of the most common ways we interact with financial markets. It is far better for the financial system as a whole to bear these risks than any one individual.

One of us (Amir) grew up in Topeka, Kansas, where the threat of tornadoes has long been hardwired in people’s minds. From an early age, Kansans go through tornado drills in schools. Kids pour out of classrooms into hallways and are taught to curl up into a ball next to the wall with their hands covering their heads and necks. These drills are done at least twice a year; school administrators know they must be prepared for a tornado striking out of the blue. Similarly, homeowners in Kansas prepare for tornadoes by making sure their homeowner insurance policy will pay them if, God forbid, their home is destroyed in a tornado. Money can’t make up for the loss of one’s home, but it ensures that a family can begin rebuilding their lives during such a desperate time. Insurance protects people—this is one of the primary roles of the financial system.

A collapse in house prices, while presumably not dangerous in terms of injury or death, presents another serious unforeseen risk to homeowners. For many Americans, home equity is their only source of wealth. They may be counting on it for retirement, or even to help pay for a child’s college education. A dramatic decline in house prices is just as unexpected as a tornado barreling down on a small town in Kansas. But when it comes to the risk associated with house prices, the financial system’s reliance on mortgage debt does the exact opposite of insurance: it concentrates the risk on the homeowner. While insurance protects the homeowner, debt puts the homeowner at risk.

Debt plays such a common role in the economy that we often forget how harsh it is. The fundamental feature of debt is that the borrower must bear the first losses associated with a decline in asset prices. For example, if a homeowner buys a home worth $100,000 using an $80,000 mortgage, then the homeowner’s equity in the home is $20,000. If house prices drop 20%, the homeowner loses $20,000—his full investment—while the mortgage lender escapes unscathed. If the homeowner sells the home for the new price of $80,000, he must use the full proceeds to pay off the mortgage. He walks away with nothing. In the jargon of finance, the mortgage lender has the senior claim on the home and is therefore protected if house prices decline. The homeowner has the junior claim and experiences huge losses if house prices decline.

But we shouldn’t think of the mortgage lender in this example as an independent entity. The mortgage lender uses money from savers in the economy. Savers give money to the bank either as deposits, debt, or equity, and are therefore the ultimate owners of the mortgage bank. When we say that the mortgage lender has the senior claim on the home, what we really mean is that savers in the economy have the senior claim on the home. Savers, who have high net worth, are protected against house-price declines much more than borrowers.

Now let’s take a step back and consider the entire economy of borrowers and savers. When house prices in the aggregate collapse by 20%, the losses are concentrated on the borrowers in the economy. Given that borrowers already had low net worth before the crash (which is why they needed to borrow), the concentration of losses on them devastates their financial condition. They already had very little net worth—now they have even less. In contrast, the savers, who typically have a lot of financial assets and little mortgage debt, experience a much less severe decline in their net worth when house prices fall. This is because they ultimately own—through their deposits, bonds, and equity holdings—the senior claims on houses in the economy. House prices may fall so far that even the senior claims take losses, but they are much less severe than the devastation wrought on the borrowers.

Hence, the concentration of losses on debtors is inextricably linked to wealth inequality. When house prices collapse in an economy with high debt levels, the collapse amplifies wealth inequality because low-net-worth households bear the lion’s share of the losses. While savers are also negatively impacted, their relative position actually improves. In the example above, before the crash, savers owned 80% of the home whereas the homeowner owned 20%. After the crash, the homeowner is completely wiped out, and the saver owned 100% of the home.

During the Great Recession, house values fell $5.5 trillion—this was enormous, especially considering the annual economic output of the US economy is roughly $14 trillion. Given such a massive hit, the net worth of homeowners obviously suffered. But what was the distribution of those losses: How worse off were the borrowers, actually?

Let’s start with an examination of the net-worth distribution in the United States in 2007. A household’s net worth is composed of two main types of assets: financial assets and housing assets. Financial assets include stocks, bonds, checking and savings deposits, and other business interests a household owns. Net worth is defined to be financial assets plus housing assets, minus any debt. Mortgages and home-equity debt are by far the most important components of household debt, making up 80% of all household debt as of 2006.

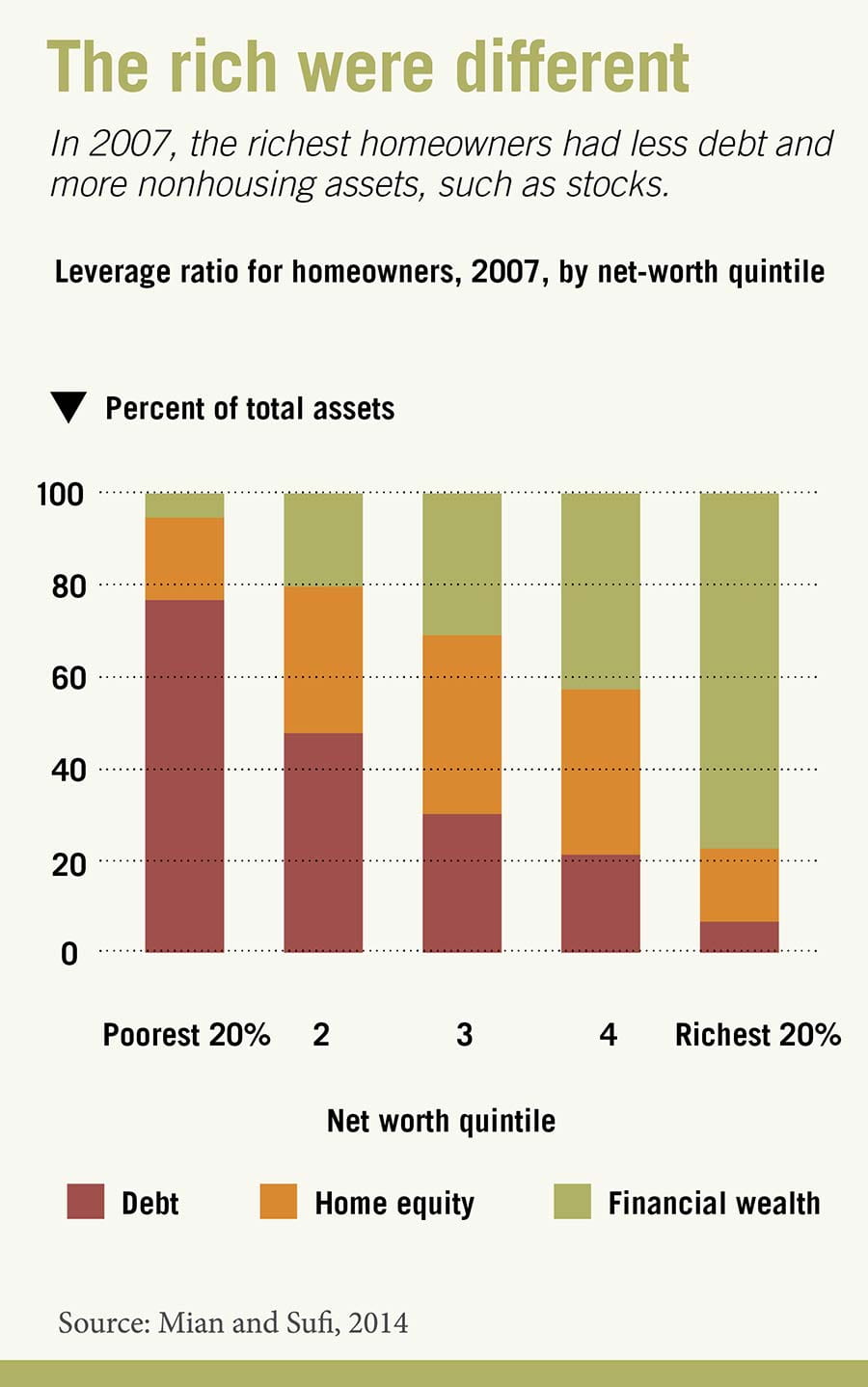

In 2007, there were dramatic differences across US households in both the composition of net worth and leverage (amount of debt). Homeowners in the bottom 20% of the net-worth distribution—the poorest homeowners—were highly levered. Their leverage ratio, or the ratio of total debt to total assets, was near 80% (as in the example above with a house worth $100,000). Moreover, the poorest homeowners relied almost exclusively on home equity in their net worth. About $4 out of every $5 of net worth was in home equity, so poor homeowners had almost no financial assets going into the recession. They had only home equity, and it was highly levered.

The rich were different in two important ways. First, they had a lot less debt going into the recession. The richest 20% of homeowners had a leverage ratio of only 7%, compared to the 80% leverage ratio of the poorest homeowners. Second, their net worth was overwhelmingly concentrated in nonhousing assets. While the poor had $4 of home equity for every $1 of other assets, the rich were exactly the opposite, with $1 of home equity for every $4 of other assets, like money-market funds, stocks, and bonds. The figure on the previous page shows these facts graphically. It splits homeowners in the US in 2007 into five quintiles based on net worth, with the poorest households on the left side of the graph and the richest on the right. The figure illustrates the fraction of total assets each of the five quintiles had in debt, home equity, and financial wealth. As we move to the right of the graph, we can see how leverage declines and financial wealth increases.

This isn’t surprising. A poor man’s debt is a rich man’s asset. Since it is ultimately the rich who are lending to the poor through the financial system, as we move from poor homeowners to rich homeowners, debt declines and financial assets rise. As we mentioned above, the use of debt and wealth inequality are closely linked. There is nothing sinister about the rich financing the poor. But it is crucial to remember that this lending takes the form of debt financing. When the rich own the stocks and bonds of a bank, they in turn own the mortgages the bank has made, and interest payments from homeowners flow through the financial system to the rich.

The figure summarizes key facts that are important to keep in mind as we enter the discussion of the recession. The poorest homeowners were the most levered and the most exposed to the housing sector, and they owned almost no financial assets. The combination of high leverage, high exposure to housing, and little financial wealth would prove disastrous for exactly the households who were the weakest.

From 2006 to 2009, house prices for the nation as a whole fell 30%. And they stayed low, only barely recovering toward the end of 2012. The S&P 500, a measure of stock prices, fell dramatically during 2008 and early 2009, but rebounded strongly afterward. Bond prices, as measured by the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index, experienced a strong rally throughout the recession as market interest rates plummeted—from 2007 to 2012, bond prices rose by more than 30%. Any household that held bonds coming into the Great Recession had a fantastic hedge against the economic collapse. But, as we have shown above, only the richest households in the economy owned bonds.

The collapse in house prices hit low-net-worth households the hardest because their wealth was tied exclusively to home equity. But this tells only part of the story. The fact that low-net-worth households had very high debt burdens amplified the destruction of their net worth. This is the leverage multiplier. The leverage multiplier describes mathematically how a decline in house prices leads to a larger decline in net worth for a household with leverage.

To see it at work, let’s return to the example we’ve been using, where a homeowner has 20% equity in a home worth $100,000, and therefore a loan-to-value ratio of 80% (and therefore an $80,000 mortgage). If house prices fall 20%, what is the percent decline in the homeowner’s equity in the home? Here’s a hint: it’s much larger than 20%! The homeowner had $20,000 in equity before the drop in house prices. When the prices drop, the house is only worth $80,000. But the mortgage is still $80,000, which means the homeowner’s equity has been completely wiped out—a 100% decline. In this example, the leverage multiplier was five. A 20% decline in house prices led to a decline in the homeowner’s equity of 100%, five times larger.

From 2006 to 2009, house prices across the country fell by 30%. But since poor homeowners were levered, their net worth fell by much more. In fact, because low-net-worth homeowners had a leverage ratio of 80%, a 30% decline in house prices completely wiped out their entire net worth. This is a fact often overlooked: when we say house prices fell by 30%, the decline in net worth for indebted homeowners was much larger because of the leverage multiplier.

Taken together, these facts tell us exactly which homeowners were hit hardest by the Great Recession. Poor homeowners had almost no financial assets; their wealth consisted almost entirely of home equity. Further, their home equity was the junior claim. So the decline in house prices was multiplied by a significant leverage multiplier. While financial assets recovered, poor households saw nothing from these gains.

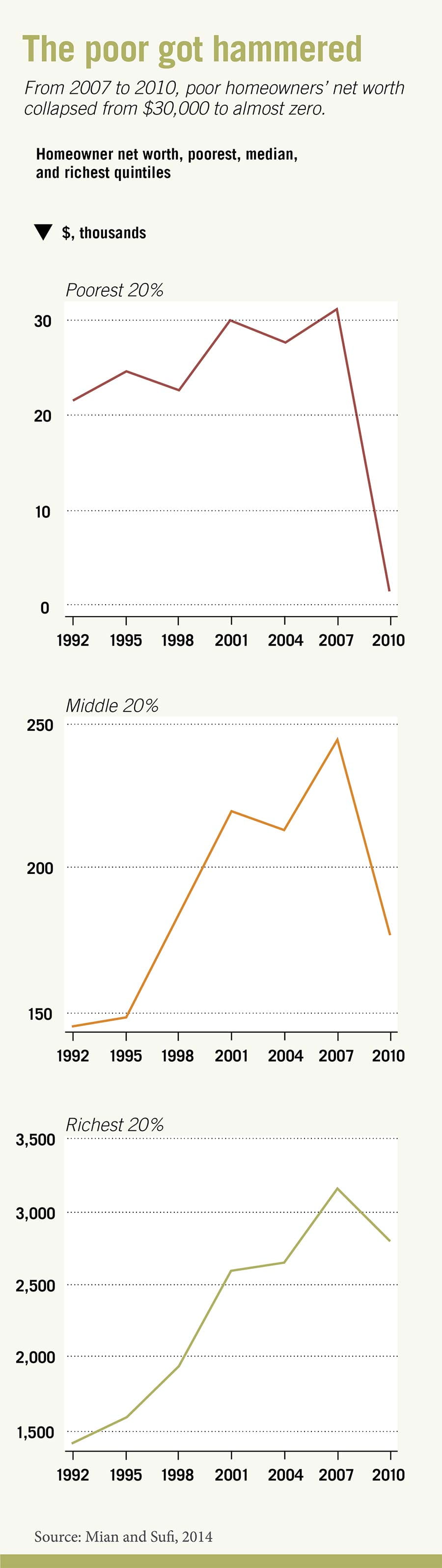

The graphs on the next page put these facts together and show one of the most important patterns of the Great Recession. They illustrate the evolution of household net worth for the bottom quintile, the middle quintile, and the highest quintile of the homeowner-wealth distribution.

The net worth of poor homeowners was absolutely hammered during the Great Recession. From 2007 to 2010, poor homeowners’ net worth collapsed from $30,000 to almost zero. This is the leverage multiplier at work. The decline in net worth during the Great Recession completely erased all of the gains from 1992 to 2007. This is exactly what we would predict given the reliance on home equity and their large amount of debt.

The average net worth of rich homeowners declined from $3.2 million to $2.9 million. While the dollar amount of losses was considerable, the percentage decline was negligible—they were hardly touched. The decline wasn’t even large enough to offset any of the gains from 1992 to 2004. The rich made out well because they held financial assets that performed much better during the recession than housing. And many of the financial assets were senior claims on houses.

High debt in combination with the dramatic decline in house prices increased the already large gap between the rich and poor in the US. Yes, the poor were poor to begin with, but they lost everything because debt concentrated overall house-price declines directly on their net worth. This is a fundamental feature of debt: it imposes enormous losses on exactly the households that have the least. Those with the most are left in a much better relative position because of their senior claim on the assets in the economy. Inequality was already severe in the US before the recession. In 2007, the top 10% of the net-worth distribution had 71% of the wealth in the economy. This was up from 66% in 1992. In 2010, the share of the top 10% jumped to 74%, which is consistent with the patterns shown above. The rich stayed rich while the poor got poorer.

Many have discussed trends in income and wealth inequality, but they usually overlook the role of debt. A financial system that relies excessively on debt amplifies wealth inequality. While there is much to learn about the causes of inequality by looking into the role of debt, our focus is on how the uneven distribution of losses affects the entire economy.

Reprinted with permission from House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright 2014 by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi. All rights reserved.

Newly digitized data gave Chicago Booth’s Richard Hornbeck and his coauthors new insight into women-owned manufacturing companies and their proprietors.

Line of Inquiry: Richard Hornbeck on the Virtuous Cycle of Women’s Participation in 19th-Century Manufacturing

The demand curve isn’t simple when lives are on the line.

Healthcare and the Moral Hazard Problem

A study of demolitions in Chicago finds they raised housing costs, hurting renters.

Infographic: How Demolishing Public Housing Increased Inequality

Booth alumni reflect on how the IMPACT Leadership Development Program nurtured their professional growth.

Example Article Swiss

With over four decades of experience in the healthcare industry, Bob Atlas has held influential roles while dedicating himself to mentoring the next generation of professionals.

Example Article Swiss

The Expanding EDE+ program, which aims to diversify the pool of students pursuing degrees and careers in economics, is undergoing an exciting transformation.

Example Article SwissYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.