How to Keep Your New Year’s Resolutions

How can you make 2024 that exceptional year when you actually keep your New Year’s resolutions? In this episode, we get advice from Chicago Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach.

How to Keep Your New Year’s ResolutionsIf you’ve ever pondered the seeming randomness of some of the superstitions we humans use to ward off bad luck—knocking on wood or throwing salt over one’s shoulder—new research suggests that these actions may not be so random after all. It turns out that there’s an underlying similarity to our superstitious rituals, at least when it comes to “undoing” a jinx. And humans seem to feel protected by this power even if they are not especially superstitious to begin with.

Associate Professor Jane L. Risen, Yan Zhang of the National University of Singapore, and Booth PhD student Christine Hosey set out to determine whether motions like knocking on wood, throwing salt, or spitting make people feel protected from a perceived jinx because they all involve gestures that push away from the body—also known as avoidant actions.

Because pushing something away from the self is associated with avoiding undesired stimuli, and because engaging in a bodily movement leads people to simulate the thoughts and feelings associated with the movement, the researchers hypothesized that exerting force away from the self may lead people to simulate the experience of having avoided bad fortune.

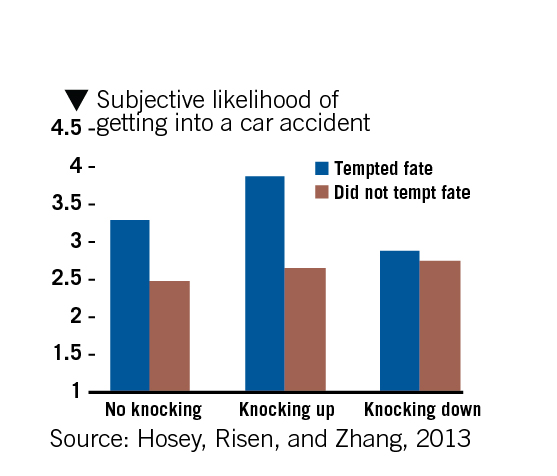

And this is exactly what they find in a series of five experiments. In one of the experiments, the researchers had participants envision a frightening scenario, such as a car accident on a snowy road, and then asked them what they thought the odds were of something like that happening to them. Some of the participants were prompted to “tempt fate” by reading a script stating something along the lines of, “No way. Nobody I know would get into a bad car accident. It’s just not possible.” Then they were told either to knock down on the top of the table at which they were sitting, or knock up on its underside (a control group didn’t knock at all). Tellingly, the people who knocked down—thereby motioning away from their bodies—rated the likelihood of getting into a car crash as much less likely than people who had knocked up or who hadn’t knocked at all.

People who knocked downwards were less likely to think an accident would occur.

This result suggests that when it comes to superstitious beliefs, there may well be something intrinsic about pushing away from versus pulling towards the self, a notion that was supported in subsequent experiments, including one in which the researchers test the hypothesis that any action that involves outwardly directed movement, however random, will have a similar “unjinxing” effect. After participants tempted fate (in the same way mentioned earlier), the researchers had them either throw a tennis ball or just hold it. As expected, throwing a ball had a similar effect on participants’ perception of bad luck as knocking down did: the unwanted event seemed less likely to occur. The last experiment revealed that even pretending to throw a ball made people feel protected from the jinx.

The string of experiments points to a human predisposition to connect the abstract to the physical. Embodied cognition theory suggests that it is important to understand the mind within the context of the physical body, highlighting the importance of bodily and sensory experiences in influencing cognition and behavior. Earlier studies have borne this out, finding that people are more likely to agree with arguments when they’re asked to nod their heads while listening. Others have shown that people experience more positive feelings toward neutral objects when they are pulling them close rather than pushing them away.

Why we’re superstitious at all is somewhat of a question mark, but one theory has it that it’s part of our basic tendency to “impose order and create meaning, even out of randomness,” says Risen. Many superstitious beliefs arise from “a shared set of heuristics, or ‘rules of thumb’, for converting complex judgments into simpler mental assessments.”

If you’ve tempted your own fate, you may just want to try knocking on wood or throwing a ball—even if you don’t believe it will work, you may convince your brain otherwise.

Yan Zhang, Jane L. Risen, and Christina Hosey, "Reversing One's Fortune by Pushing Away Bad Luck," Journal of Experimental Psychology, August 2013.

How can you make 2024 that exceptional year when you actually keep your New Year’s resolutions? In this episode, we get advice from Chicago Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach.

How to Keep Your New Year’s Resolutions

Researchers will be able to generate synthetic but photorealistic faces that can be tuned along sets of perceived attributes.

Looking for a Trustworthy Face? There’s a Photo Database for That

Making the process of self-correction too explicit can make it less effective.

The Hazards of Second-GuessingYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.