Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?

To what extent are we accountable for what goes into index funds?

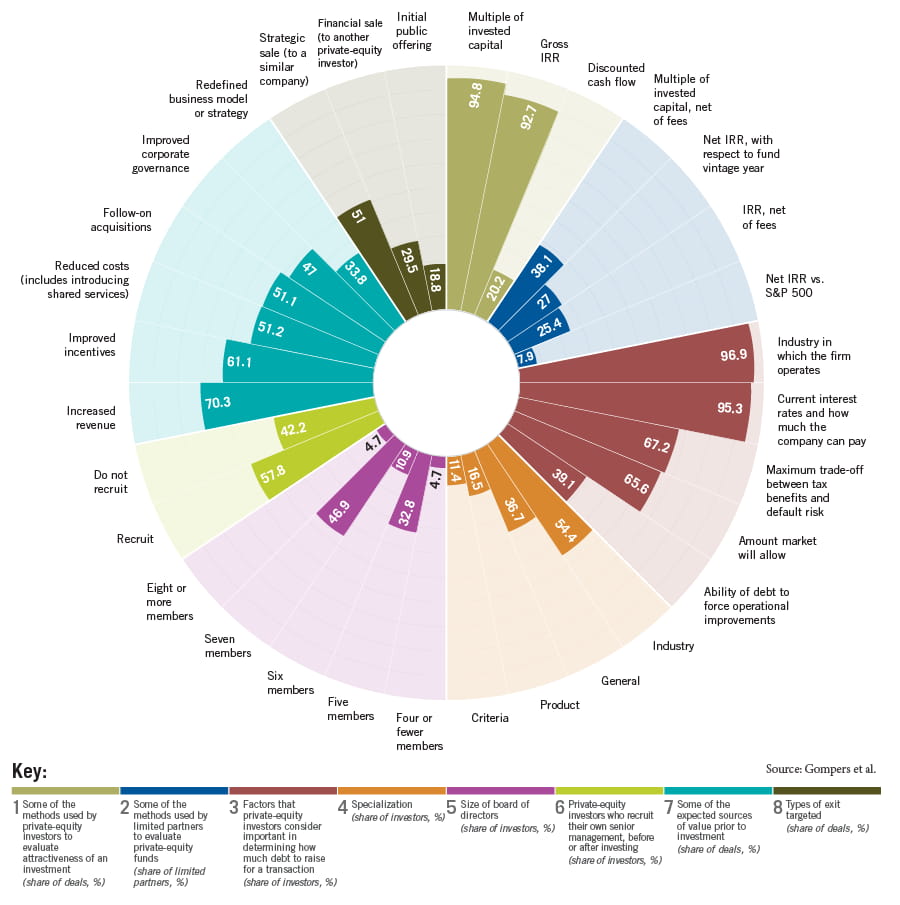

Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?Private-equity funds have established a reputation for strong returns, having outperformed the S&P 500 by roughly 4 percent annually over the past three decades. What they have done to achieve those returns, however, has been less well documented. So Harvard’s Paul Gompers and Vladimir Mukharlyamov, along with Chicago Booth’s Steve Kaplan, went right to the source to ask private-equity-fund managers about their strategies and practices. In analyzing responses from 79 fund managers collectively managing more than $750 billion in assets, the researchers find that real-world private-equity approaches don’t always match the financial-theory best practices taught at leading business schools—or the practices for which private equity is most notorious in the public imagination. Among other things, private-equity investors favor some metrics far more than others when evaluating investments (they rely heavily on internal rate of return, or IRR, and multiples of invested capital in comparison to net present value and discounted cash flow); they use absolute performance targets; and they tend to add value by focusing on growth. Here are a few more snapshots taken from within the black box of private equity.

Paul Gompers, Steve Kaplan, and Vladimir Mukharlyamov, “What Do Private Equity Firms Say They Do?” Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

To what extent are we accountable for what goes into index funds?

Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?

Recognize the stressors inherent in business models.

Four Ways to Avoid the Next Silicon Valley Bank

When negotiations are mediated by third-party brokers, success is tied to getting the deal done as quickly as possible.

Want a Deal? Get It Done FastYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.