In cricket, technology has helped challenge and correctly reverse umpire calls.

- By

- December 01, 2015

- CBR - Economics

In cricket, technology has helped challenge and correctly reverse umpire calls.

How often are umpires wrong? When they’re wrong, what kinds of errors do they make? And do they show favoritism to the home team?

In many competitive settings—say, a financial trading floor—professionals don’t typically get the chance to review their decisions and reverse them without cost, even when they’re later found out to be mistaken.

But in cricket, the Decision Review System (DRS), introduced in November 2009, allows teams to challenge umpire rulings and have them analyzed by a third, off-field umpire with access to audiovisual technology, introducing a new level of precision to decisions.

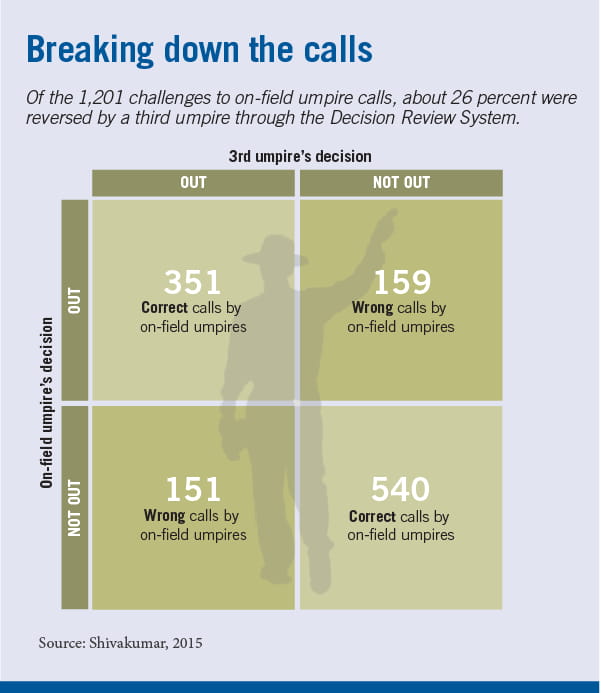

Combined with ESPN’s extensive cricket stats, the DRS has given researchers an exceptional opportunity to learn about how well umpires make decisions, and how technology is changing the game. Chicago Booth’s Ram Shivakumar uses the data to create detailed analyses of 126 cricket matches held between 2009 and 2014, focusing on 1,201 challenges to on-field umpire decisions. He finds that about 26 percent of on-field umpire calls that get challenged are reversed upon review—making the conditional error rate, in which only challenged decisions are counted, much higher than the unconditional 8 percent touted by the International Cricket Council.

These reversals are not evenly distributed among all call types, however. Shivakumar uses logistic regressions to determine that among challenges to leg-before-wicket (LBW) decisions—which make up three-quarters of all challenges—outs called by the on-field umpire are 75 percent to 182 percent more likely to be reversed than not-outs. “Simply stated, when it comes to LBWs, on-field umpiring errors have been biased against [the] batsman,” Shivakumar writes, noting that prior to the DRS, it was customary for umpires to give batsmen the benefit of the doubt. By contrast, among challenges to decisions that involve catches, not-out calls are as likely to be reversed as outs.

Is there any evidence of bias by the third umpire in favor of the home team? There’s some prior evidence for umpires’ home-team bias, but it does not appear to extend to the third, off-field umpire, who has the benefit of more time and resources to make calls, according to Shivakumar. It’s equally likely for a home team or an away team to successfully challenge a decision.

The DRS, despite having demonstrably improved the quality of decision making in cricket, has not been met with universal approval within the sport. If only there were an equivalent technology for the workplace.

Ram Shivakumar, “What Technology Says about Decision-Making: Evidence from Cricket’s Decision Review System (DRS),” Working paper, August 2015.

Turkey’s experience suggests ‘place-based policies’ can have unintended effects.

Does Targeting Aid Help Poorer Regions?

Three experts discuss the sources of income inequality.

Why Are the Very Rich Getting Even Richer?

When prices are rising in the 3–4 percent range, savvy shoppers can exploit the power of competition among retailers.

Bargain-Hunting Households Can Beat InflationYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.