Spiritual Guidance Is Hard to Automate

Human religious leaders benefit from their perceived authenticity.

Spiritual Guidance Is Hard to AutomateSay you’re at the doctor’s office and need a shot in the buttocks. To distance yourself from the awkward situation, you may take steps—such as avoiding eye contact or small talk, or smiling less—to offset the intimacy involved.

This seemingly unfriendly behavior toward a service provider is a reaction to intimate services, according to research by University of California at Berkeley’s Juliana Schroeder, Chicago Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Kurt Gray and Chelsea Schein, a PhD candidate.

The reason has to do with what Schroeder and her coresearchers dub “functional intimacy.” Behavioral scientists have previously studied and established two other kinds of intimacy: “relationship intimacy,” experienced intentionally with people we’re close to, and “imposed intimacy,” the unwitting closeness that people might experience, say, on an overcrowded subway car.

But in this third type, people have a purpose that needs fulfilling that also brings with it an undesired intimacy. This can create some cognitive dissonance, at a doctor’s office, say, or at the airport when receiving a security pat-down. The researchers find that in situations of functional intimacy, people become socially awkward in a bid to distance themselves psychologically.

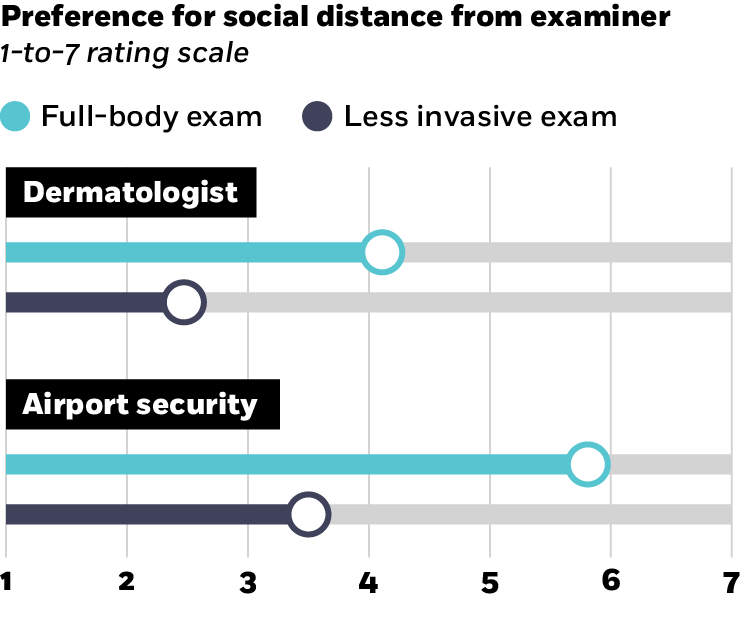

In one experiment, the researchers had people imagine one of several scenarios, which included receiving a vaccine in the buttocks and being patted down by an airport security officer. Study participants said they preferred less social interaction when the exchange was more intimate.

The researchers also tested the phenomenon in real, rather than imagined, settings. In a flu clinic at the University of Chicago, people who were primed to expect a more-intimate exchange said they planned to have less social interaction with the nurse.

When asked to hold hands with a stranger, people in both a lab setting and a museum minimized their physical interaction with the other person more so than they did when asked to simply shake hands with someone they didn’t know. The hand-holders made less eye contact and “turn[ed] their body away from that person so they’re literally minimizing social interaction,” Fishbach says. “People psychologically distance themselves from functionally intimate interaction partners.”

This kind of behavior can lead nurses, security agents, and other service providers to feel isolated, dehumanized, and stressed—but understanding the psychological impulse behind such distancing attempts could help them not to take the reactions personally, says Fishbach, who adds it’s also important for those who manage these service providers to offer social support.

Juliana Schroeder, Ayelet Fishbach, Chelsea Schein, and Kurt Gray, “Functional Intimacy: Needing—But Not Wanting—the Touch of a Stranger,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, in press.

Human religious leaders benefit from their perceived authenticity.

Spiritual Guidance Is Hard to Automate

Most people agree that deception is ethical in these situations.

Eight Ways in Which Lying Is Seen as Moral

We put greater value on things other people want but can’t have—just because they can’t have them.

What Drives Our Desire for ExclusivityYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.