Stereotypes Skew How Much We Say about Misfortune

The implications of ‘surprised elaboration’ can be profoundly consequential.

Stereotypes Skew How Much We Say about Misfortune

Edmon De Haro

Hard-thinking people have spent millennia trying to articulate what distinguishes us from all other creatures. Is it having opposable thumbs? Walking upright? Using tools? Thinking analytically? This question finally got a fairly clear answer several years ago thanks to researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Germany, who brought in 105 human two-year-olds in order to compare their intellectual performance on essentially two different measures of IQ with that of 106 chimpanzees and, just for good measure, another 36 orangutans.

In tests that required reasoning about physical objects—things such as being able to track where a reward is placed under a cup, or being able to use a tool to solve a problem—the toddlers were basically neck and neck with the other primates in their performance. But in tasks where some social intelligence was involved, where subjects had to be able to track what was going on in someone else’s mind and respond accordingly—such as following the path of someone’s gaze, or understanding what someone was intending (but failed) to do—the human toddlers crushed the competition.

It makes sense that we’re good at this sort of social thinking: we are literally built for it. Our human brain stands out in the animal kingdom for its relatively gigantic neocortex—the fat part just above your eyes. What’s all that neural capacity good for? Lots and lots of things, but what it really seems to be designated for is social stuff.

If you look across primate species, what you see is that the size of the neocortex relative to the rest of the brain is positively correlated with the size of the social group that primate species inhabits. The larger the social group, the larger the neocortex relative to the rest of the brain. Human beings are the most social of all primates, and we also have the largest neocortex relative to the rest of the brain. Living in large social groups requires having a tremendous amount of neural capacity to keep track of who knows what, who believes what, who likes what, who should be trusted and who should be avoided, and so on. Living in large social groups is also easier if you have some capacity to anticipate others’ actions before they make them, meaning that the ability to interpret somebody’s behavior in terms of an underlying mental state or goal is also invaluable. It’s our social intellect, not our thumbs, or our posture, or anything else, that makes human beings so special.

But while we are good at reading the mental states of others—relative to other animals—we are not perfect at it. Such states are, after all, invisible. For 2,500 years, the branch of philosophy known as solipsism has been teaching that one can’t really be sure that another’s mind (or anything else outside of one’s own mind) even exists. But assuming you can get past that question, as nearly everyone can, the intangible nature of mental activity still presents a real challenge in making accurate inferences about what’s going on in other people’s minds.

Two phenomena lead us to make a lot of mistakes in this regard. The first is anthropomorphism, or the humanization of a nonhuman agent. When psychologists ask people what separates humans from nonhumans, most do not start talking about their neocortexes; instead, most people will describe capacities of the mind, particularly those related to thinking and feeling. When we anthropomorphize a nonhuman entity—whether it’s a pet, a car, or a consumer product in a marketing campaign—we attribute human thought and feeling to it, often in a subtle way.

The opposite also happens: cases of dehumanization. These are cases where we regard other people who presumably do have typical human capacities to think or to feel as though they don’t. Dehumanization typically involves treating other people as if they’re idiots, and so not capable of thinking, or as if they’re animals, unable to experience compassion, or empathy, or other sophisticated emotions that humans feel.

You don’t have access to the mind of another person, so sometimes you may question whether another person actually has anything going on in his mind at all.

You can see both phenomena in the world. Modern technology is pushing the boundaries of anthropomorphism. We now have devices that talk to us, that answer questions for us, that perform tasks for us. I don’t think it’s an accident that these tools are called smart technology, as if they can think and possess actual intelligence. Anthropomorphism is rampant in marketing and product design because it works. People who referred to their cars by name, in one series of studies, held onto them for longer than those who did not. Trading in a heap of mindless steel is one thing, but trading in your named family car is quite another.

We can find plenty of examples of the inverse as well. In the United States, when the National Football League was considering expanding its season from 16 games to 18, Ray Lewis—a linebacker many consider among the fiercest competitors the league has ever had—and other players were concerned about the toll that two extra games would take on their bodies. Lewis objected that players had essentially been dehumanized, treated as consumer products for other people’s enjoyment, and had thereby been made to be seen as unfeeling objects. He said, “I know the things that you have to go through just to keep your body functioning. We’re not automobiles. We’re not machines. We’re humans.” It’s nothing to send objects out onto the field for a couple more games of extreme violence, but it’s quite another thing to send out men already suffering through a grueling season.

But perhaps the most obvious context for dehumanization is politics. When one person sees the world one way and another person sees the world in a different way, rather than acknowledging that the other person has a different belief or attitude or thought, a natural tendency for many people is to question whether she is capable of thinking at all. We see it when the Left looks at the Right, and when the Right looks at the Left. When you use words such as monster, crazy, idiot, or madman, these are inherently concepts that suggest you’re not just questioning another person’s thoughts; you’re questioning another person’s capacity to think.

The general explanation for this goes back to the opacity of other people’s mental processes. After all, there’s only one mind you have access to, and that’s your own. You know all the thoughts and feelings that you have going on between your ears. You know how much you agonized over the last election, for instance, or what your own experience of pride or shame or embarrassment or guilt is like. You can’t feel that in other people. You don’t have access to the mind of another person, so sometimes you may question whether another person actually has anything going on in his mind at all.

So how do we actually go about solving this problem of other minds? The solipsists are right that you can’t see the mind of another person, but my research suggests you can hear it. Hearing somebody talk is the closest you’re ever going to get to their ongoing mental experience, and it’s not just the content of the words that provides this. Paralinguistic cues of all sorts provide honest signals for the presence of thinking and feeling.

In research that University of California at Berkeley’s Juliana Schroeder (a Booth PhD graduate) and I did, we had 20 participants come into our lab and tell us two stories, which we recorded on video. One was a story about something that happened that was really emotionally positive for them, and the other was a story about something really emotionally negative that happened to them.

For each story, this left us with three basic components: the text of their story, stripped of all other information; the audio, which combined the information of the text with whatever information was conveyed by the storyteller’s voice; and the video, which combined the semantic and auditory information with the visual cues of body language and facial expressions. We had a couple hundred evaluators either watch, hear, or read one of these stories and then report their impressions of the person.

The findings were intriguing to us. For evaluators who saw only text, their perception of the storytellers’ capacity to think was dramatically lower than for those evaluators who received the story through audio or video. But it turned out that being able to see the storytellers, as opposed to just hearing them, didn’t substantially change participants’ impressions of the speakers. It appears that many cues that indicate capacity for thought—tone, volume, pace—come through the voice.

These data suggest that the voice may be doing a lot more work than you might think. In many contexts of daily life, the cues people pick up on can be confounded, because they often see others when they’re hearing them. We find, though, that people tend to think they’re getting a lot of information from body language, when in fact, much of the information they’re using is actually coming from the voice.

We then conducted a similar study, but instead of instructing them to discuss an emotional situation, we asked the storytellers to describe a mental situation—a thought, a decision they had—that turned out well or poorly. And again, we found a consistent effect of the text-only condition in which the storytellers seemed more mindless and less thoughtful than when evaluators heard them or watched them tell the story. Again, seeing the person tell the story didn’t make much difference for the evaluators’ impressions.

Study participants generally regarded people more highly when they heard them speak, even when they disagreed with what they were saying.

Schroeder et al., 2017

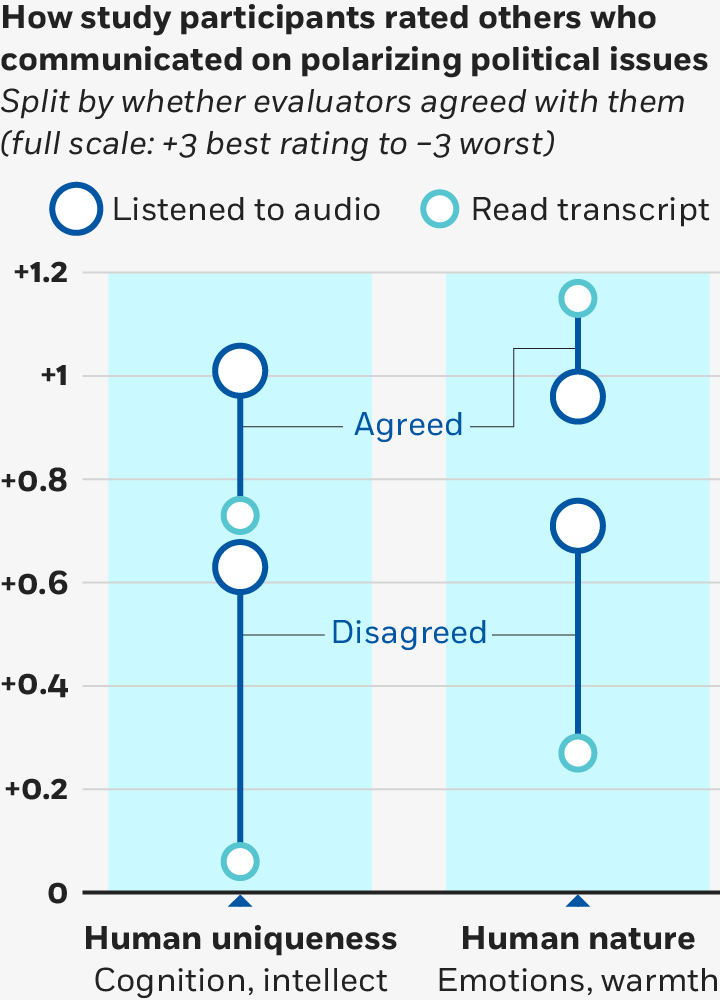

As I’ve noted, however, one of the easiest ways to observe dehumanization of this kind is to get people thinking about politics. So Juliana Schroeder, Chicago Booth PhD candidate Michael Kardas, and I ran an experiment in our lab here in downtown Chicago in which we had six participants come in and explain their beliefs about one of three polarizing topics: abortion rights, support for the Afghan War (this was around 2013), and preference for rap or country music. They were then evaluated by several hundred other participants—whose own opinions represented both sides of these topics—who then reported their impressions of the speakers after watching, hearing, or reading them explain their positions.

As you might expect, it was the cases in which evaluators disagreed with the speakers that they tended to dehumanize them. But we found, again, that people seemed less refined, cultured, rational, logical, and sophisticated—all capacities having to do with thinking—when evaluators read what they had to say, but there was no statistically significant difference between hearing them and watching them. We didn’t see the same pattern of results for evaluators who agreed with the person. People tend to be egocentric and assume that if they agree, the other person is thinking in a way that’s similar to them, so the medium through which they’re communicating does not matter as much.

To test the robustness of this pattern of results, we ran similar experiments during the primaries for the 2016 US presidential election and on the weekend before the general election itself. Groups of people, representing support for different candidates, each explained whom they were voting for and why. Other people, across the political spectrum, watched, listened to, or read those explanations and reported their impressions. We again found the same pattern of results: spectators dehumanized respondents they disagreed with, but this tendency was dramatically reduced when they could hear the respondents’ voices.

Most people aren’t mindless idiots. But when we read what someone has said, the cues that reveal the presence of a thoughtful and intelligent human being are stripped out of the interaction. And when it happens to be somebody we disagree with, people do not seem to readily put those cues back in.

Fortune 500 recruiters preferred audio recordings of job pitches over written pitches specifically composed to be read.

Schroeder and Epley, 2015

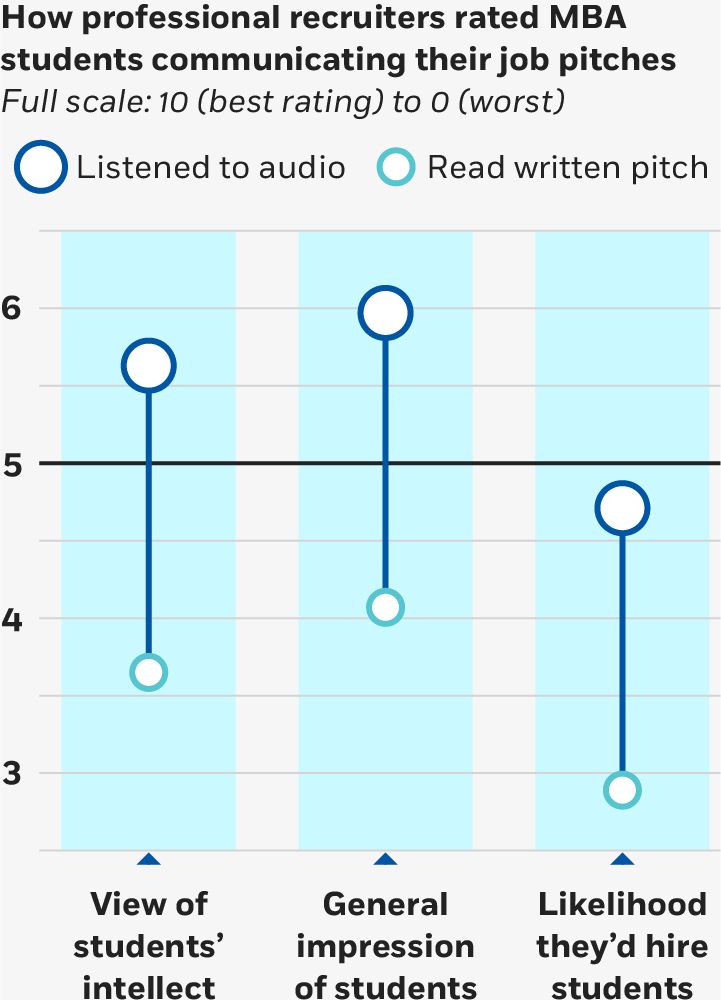

Our tendency to dehumanize more or less according to the medium we’re using matters not just when we’re evaluating other people, but also when other people are evaluating us. All MBA students know how to give an elevator pitch, and most have rehearsed their personal pitch to recruiters—I suspect if you called one at 3 a.m. and asked for her pitch, she could recite it without lifting her head from the pillow—so Juliana Schroeder and I asked some Booth students to come in and give us theirs. Specifically, we asked for the pitch they’d give to their ideal employer, and then we again created video, audio, and written versions of each pitch. We also asked each student to write a pitch, because there could be meaningful differences between a pitch specifically composed to be read and one composed to be heard or watched.

We then asked evaluators to imagine that they were employers and report their impressions of how confident the person seemed, and how thoughtful, intelligent, and competent. They gave us their general impression, assessed how likable the person was, and indicated their interest in hiring the person.

It may not surprise you to learn that when the evaluators heard the students, as opposed to reading either their written pitch or a transcript of their spoken pitch, they described them as seeming more thoughtful, intelligent, and rational. They had a more favorable general impression of the participants, and they were more interested in hiring them. Again, adding video didn’t make much of a difference. What’s more, we got similar results when we repeated this experiment using actual Fortune 500 recruiters as evaluators instead of participants acting as employers.

Human history is long. Homo sapiens emerged on the planet somewhere around 300,000 years ago, but it took us about 295,000 years to start writing to each other. In all the intervening time, our brains evolved to communicate with each other in a particular way: face-to-face. We had physical interactions laced with voice or visual cues. As a species, we learned to communicate, to convey our states of mind, under those conditions.

And if writing is a recent innovation on the timeline of human history, electronic media are virtually brand new. It’s not surprising that we might find some gaps in our ability to use these tools especially effectively.

For instance, if I wanted to create a maximally dehumanizing medium for communicating with other people, I couldn’t do better than Twitter. Twitter is not only a largely text-based medium, but it is also a psychologically distancing medium. Other users are often identified by “handles” rather than by their own names, and the people you write to are “out there” on the internet somewhere rather than “right here” having a direct conversation with you. Add to that a character limit that makes it impossible even in text to communicate sophisticated or nuanced thought and you have the perfect platform for making other people seem like unthinking objects or unfeeling animals.

Facebook is a little more complicated. It was intended to connect people with each other. But it turns out that social connection is to Facebook what sugar is to Diet Coke: it seems like it’s there, but research again suggests not. My collaborators and I have found in experiments time and again that talking to others in person makes people feel better than they expect it will. It doesn’t even matter what they talk about—shallow stuff, deep stuff, whatever—they tend to love it more than they expect. But research on Facebook users finds that the more people use Facebook, the worse it seems to make them feel.

You might imagine that we’ll get better at using this technology over time. We’ll get better at using Twitter and Facebook and text-based media interaction in general over time. I don’t think so. Our data suggest that there’s something inherently dehumanizing about the cues that are present in text-only information. And you can’t artificially add cues, such as a person’s voice, into a text-based medium of communication that doesn’t include them to begin with. The only way you can do that is to use a voice-based medium instead.

Perhaps the most important question to ask is whether we are sufficiently media savvy to have a sense of these kinds of effects. Again, I think the answer is no. For one thing, avoiding the specific phenomenon I’ve been describing, the tendency to dehumanize in text-based communication, appears not to be intuitive for many people. We asked about a thousand participants in an online survey: If you were making an elevator pitch and wanted to be perceived as most intelligent, how would you choose to express your thoughts to someone? Would you choose to write or would you choose to speak? Seventy percent said they’d opt for writing.

Moreover, the medium through which we communicate with other people is often overlooked; the idea that we could be interacting with somebody through a different medium often doesn’t occur to us when we are in the midst of an interaction. I did a study some years ago with Justin Kruger, Jason Parker, and Zhi-Wen Ng, all then at the University of Illinois, in which we compared voice recordings to email, with participants sending messages via each that were either sincere or sarcastic. Not surprisingly, email recipients were not great at detecting sarcasm: their accuracy rate was 56 percent, not significantly better than random guessing. When they heard the message spoken aloud, of course, they were much more accurate. But just as important, both senders and receivers overestimated how easily sarcasm would be detected over email. They had no sensitivity at all to how the medium was affecting the message being conveyed.

This is particularly important because people’s preferred mode of communication is not necessarily the most effective one. University of Texas at Austin’s Amit Kumar and I have found in recent experiments that people tend to prefer email over a phone call, at least when it comes to reaching out to an old friend. Specifically, they expect a phone call to be more awkward, but when we put these two modes of communication to the test, we find that it’s not. Again, I think this suggests a misunderstanding of how media affect interactions.

The primacy of voice in communicating state of mind may not be completely intuitive when you communicate with all of your senses intact. But Hellen Keller, who lacked both hearing and sight, understood the importance of voice powerfully through her lived experience. Keller was once asked to speak at a conference advocating for kids who were also deaf and blind. In a letter to the organizer explaining why she was unable to attend, she wrote,

I’m just as deaf as I am blind. The problems of deafness are deeper and more complex, if not more important than those of blindness. Deafness is a much worse misfortune, for it means the loss of the most vital stimulus—the sound of the voice that brings language, sets thought astir, and keeps us in the intellectual company of man. . . . I’ve received letters from the parents of children who are either deaf or feebleminded. The parents could not say which. The doctor did not know or else he did not tell them the truth.

We don’t speak of other people being feebleminded anymore, but I think the tendency to infer that someone who lacks a voice, whom we don’t hear from directly, might be less mentally capable than other people still shows up in all of the data that we’ve been collecting. Technology can continue to develop new and more innovative modes of text-based communication, but it may never recreate the cues to another’s mind contained in the human voice.

Nicholas Epley is the John Templeton Keller Professor of Behavioral Science and the Neubauer Family Faculty Fellow at Chicago Booth. This essay is adapted from a presentation delivered at the Kilts Center’s Marketing Summit 2019.

The implications of ‘surprised elaboration’ can be profoundly consequential.

Stereotypes Skew How Much We Say about Misfortune

You can’t fix all the world’s problems, so pick your battles.

What a Hot Dog Taught Me about Ethical Priorities

Four lessons in supply and demand to help combat global pandemics

How to Vaccinate the World (Next Time)Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.