Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?

To what extent are we accountable for what goes into index funds?

Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?In the US, quarterly earnings reports are a responsibility as old as the Securities and Exchange Commission itself: public companies have been required to file them since 1934. Corporate short-termism, in which executives prioritize quarterly successes over long-term goals, has become a bugbear of industry leaders and policy makers alike—leading some to suggest getting rid of quarterly reports altogether. The Initiative on Global Markets at Chicago Booth ran an Economic Experts Panel poll on the idea.

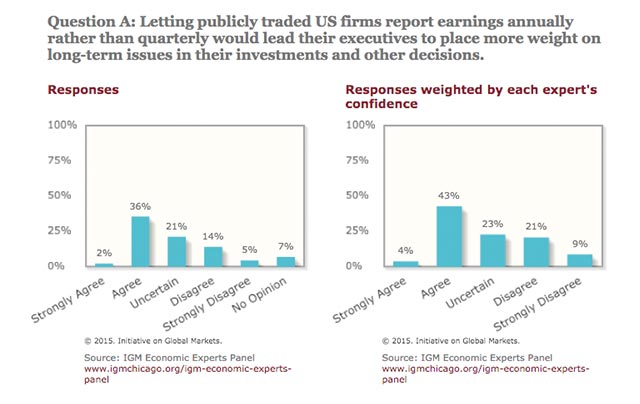

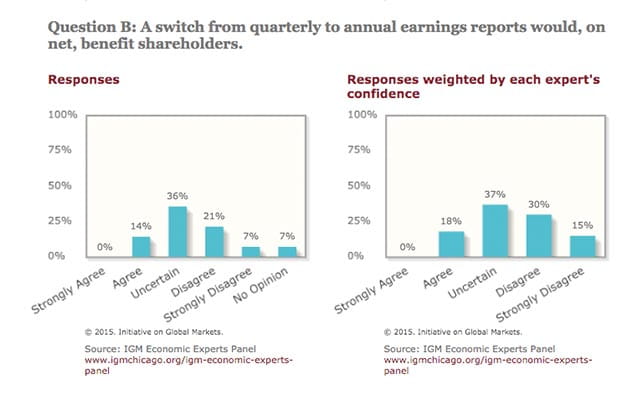

Do leading economists think that filing earnings reports annually, as opposed to quarterly, would induce executives to place a higher priority on long-term issues? Nearly 40 percent agree or strongly agree. Do they think such a switch would present a net benefit to shareholders? That’s another story—nearly 30 percent disagree or strongly disagree.

Oliver Hart of Harvard agreed, with a caveat: “I am in favor of letting firms do this, but only if it is part of their charter or approved by their shareholders. It should not be a blanket rule.”

Kenneth Judd of Stanford, however, strongly disagreed, with a critical eye to accountability: “This would increase the information difference between insiders and outsiders. Management would have more time to hide their mistakes.”

Caroline Hoxby, Judd’s colleague at Stanford, disagreed on different grounds: “Smart investors are perfectly capable of evaluating firms using a combination of multiple quarterly reports.”

Robert Hall of Stanford disagreed: “Public markets need certified disclosure regimes. Businesses that are harmed by disclosure should be private.”

Bengt Holmstrom of MIT strongly disagreed: “One year [is] far too infrequent for well-functioning markets.”

Larry Samuelson of Yale remained uncertain: “The modest push toward better weighting of long-term issues must be balanced against the attendant loss of information and accountability.”

To what extent are we accountable for what goes into index funds?

Are You Responsible for Your ‘Passive’ Investments?

Rising rates have exposed landlords’ significant interest-rate risk.

Why South Korea’s Housing Market Is So Vulnerable

A historical case study sheds light on the effects of bigger financial institutions.

Line of Inquiry: Kilian Huber on Who Benefits When Banks Get BiggerYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.