Why a Soft Landing Is So Hard

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan describes the task ahead for the US Federal Reserve.

Why a Soft Landing Is So Hard

Chris Gash

Donald Trump supporters became significantly more optimistic about the economy after he was elected president, playing out a partisan split over economic perceptions that has become commonplace among the US electorate. As decades of political-science research have demonstrated, supporters of the party in the White House typically think the economy is in better shape than supporters of the opposition party do.

But though each presidential election is accompanied by a jolt of economic optimism from voters in the victorious party, neither the Trump supporters nor the supporters of winners in the four previous US presidential elections have let their newfound confidence affect their spending habits, according to research by Princeton’s Atif Mian, Chicago Booth’s Amir Sufi, and Nasim Khoshkhou of Argus Information and Advisory Services. Although economists generally predict that consumers with optimistic economic expectations will boost their spending, Trump voters didn’t display such behavior in the aftermath of the election, according to the findings.

The research is an extension of work Mian, Sufi, and Khoshkhou started before Trump’s election, in which they uncover that optimism inspired by political elections doesn’t necessarily translate into spending. (For more, see “Relax, US elections don’t drive consumer spending,” Winter 2015.) Analyzing county-by-county results for presidential elections between 2000 and 2012, they find that election-driven consumer sentiment and spending didn’t necessarily match up. After Obama’s 2008 election, voters in areas that generally opposed him said they planned to purchase less, but their actual spending didn’t change.

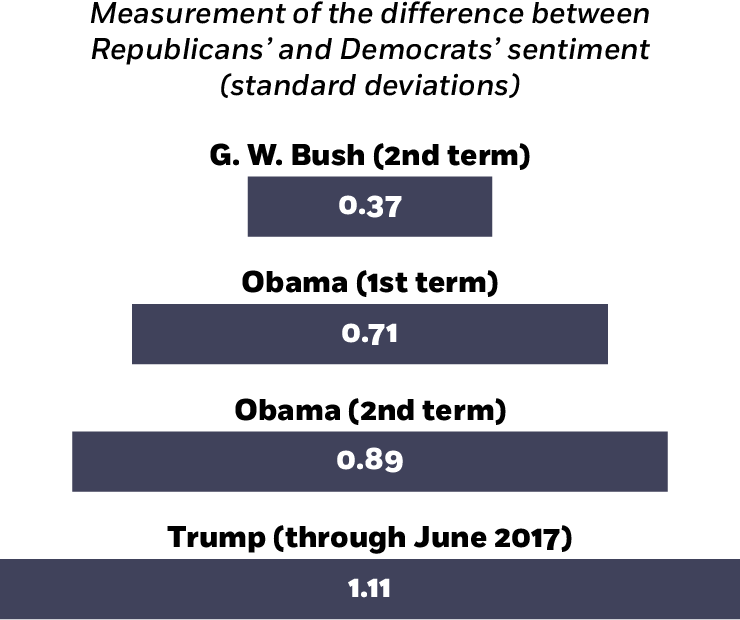

Growing divide between Republicans and Democrats

The gap between the parties has widened over the last four terms.

Mian et al., 2017

After Trump’s election, the researchers looked again at the opinions and consumer habits of voters, analyzing optimism and spending patterns on a countywide level. They looked at data sources including surveys and polls of individual voters, as well as county-level data reflective of sales such as new-car registrations and credit-card spending. They find little evidence of a spending bump.

The cumulative results indicate that over the past 20 years, the partisan effect has grown increasingly strong, widening the gap in economic expectations between the winning and losing camps. Trump’s election led to an unprecedented relative increase in optimism, eight to nine times larger than the election of George W. Bush in 2000, and three to four times larger than the effect following Barack Obama’s elections in 2008 and 2012.

The researchers find support for the notion that the expectations gap created by electoral results is the product of partisanship rather than other factors, such as policies that benefit one party’s voters more than the other’s. Looking at state- and county-level data, the authors find there’s little to suggest that “economic circumstances change to the benefit of areas supporting the new president after elections.” In fact, even Democrats and Republicans within the same zip code have profoundly different outlooks on the future of the economy.

Economic sentiment doesn't translate into spending

Looking at Republicans' spending over the last five US presidential election cycles, the researchers find that spending habits changed little.

Mian et al., 2017

Despite Trump supporters’ upbeat expectations, as was the case following earlier elections, optimism doesn’t appear to have translated into spending. Though Republican respondents to a Gallup survey question did report a 6 percent increase in spending after the election, Republicans polled by the University of Michigan didn’t feel it’s a better time to buy durable goods, such as appliances, electronics, or furniture. Data on actual (as opposed to reported) spending also don’t reflect an increase: as of June 2017, the counties that voted heavily in favor of Trump had seen no increase in car buying. This extends the pattern the researchers identified before the election, but “the evidence for the 2016 election is most striking,” they write.

For economists, the findings call into question the practical interpretations of economic expectations. When researchers ask a consumer how healthy she expects the economy to be five years out, they typically treat the answer as a reflection of the individual’s expectations about her own potential income, and therefore spending power. But this study suggests postelection optimism doesn’t necessarily lead to economy-boosting spending.

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan describes the task ahead for the US Federal Reserve.

Why a Soft Landing Is So Hard

UCLA’s Sebastian Edwards joins Bethany McLean and Luigi Zingales to discuss the implementation of market-oriented policies in Chile.

Capitalisn’t: Key Lessons from the ‘Chicago Boys’ Chile Experiment

Experts in finance and economics consider the costs and benefits of the US’s contentious cap on borrowing.

Does the Debt Ceiling Do More Harm than Good?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.