A Good Boss Can Boost Team Productivity

A study of two multibillion-dollar retail chains homes in on managers.

A Good Boss Can Boost Team Productivity

Associated Press

Modern cancer treatments are growing increasingly successful—and unaffordable. “We face a future where life-saving treatments are effectively unavailable for a large segment of the population,” write Chicago Booth’s Ralph S.J. Koijen and Columbia’s Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh.

Cancer, among the leading cause of death worldwide, kills millions of people each year. Researchers are discovering new treatments: MD Anderson Cancer Center’s James P. Allison and Kyoto University’s Tasuku Honjo shared a 2018 Nobel Prize for their pioneering work in immunotherapy.

However, the treatments they made possible are expensive to the point of being beyond reach for many patients. Koijen and Van Nieuwerburgh observe that a standard 12-week treatment for melanoma costs more than $159,000 in the United States, and the price of cell therapy treatment for blood cancers can approach $500,000. While health insurance may cover much of the cost, out-of-pocket expenses including deductibles, co-pays, and insurance premiums can still be ruinous. Cancer patients with private insurance under the Affordable Care Act today may pay $20,000–$33,000 out of pocket, the researchers calculate.

Meanwhile, as cancer patients live longer, life insurers reap a “large windfall” of $7 billion annually, the researchers find. This represents a sizeable chunk of the industry’s profits: the life- and health-insurance industries reported combined 2017 net income of $39 billion.

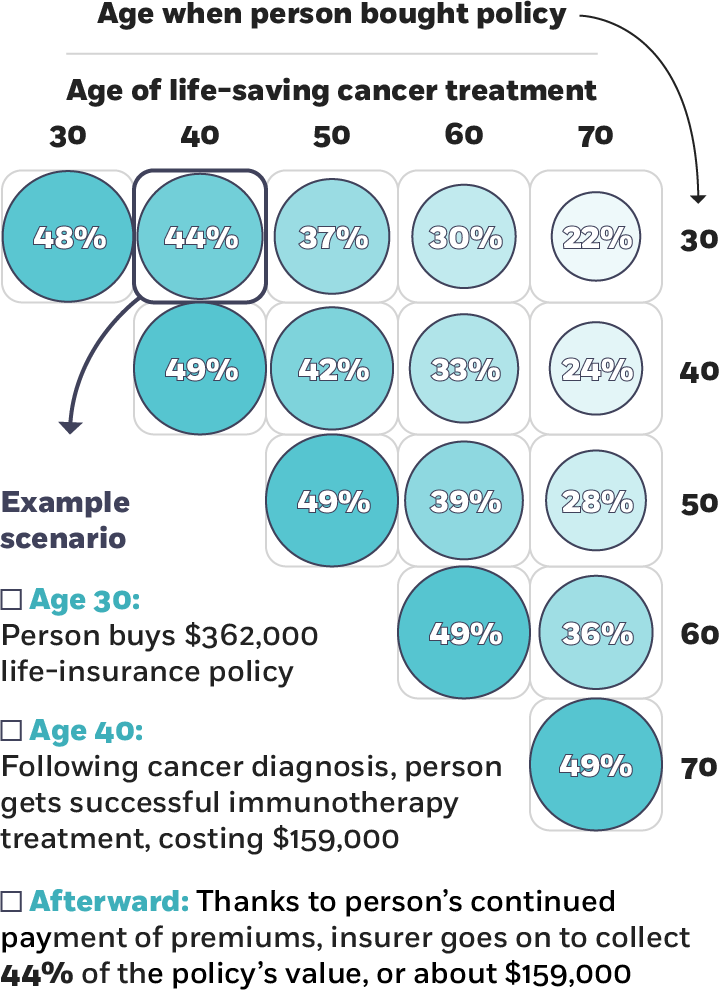

The benefit to insurance companies when customers beat a cancer diagnosis

Percentage of life insurance policy’s death benefit collected from customers’ continued payment of premiums

Koijen and Van Nieuwerburgh, 2018

The researchers offer two proposals, depending on the bargaining power of life insurers relative to consumers. If consumers have most of the bargaining power, life-insurance companies can share some of their windfall to contribute to patients’ out-of-pocket costs. This, the researchers write, would help patients access treatment and maintain financial stability, and would also make life insurance a more valuable product.

Koijen and Van Nieuwerburgh used data from clinical studies of people with metastatic melanoma. They find that a life-insurance policy with a death benefit of $362,000 would more than cover the $159,000 cost of a 12-week melanoma treatment. Even a policy with a face value as little as $45,000 would be enough to cover a patient’s out-of-pocket costs of $20,000, according to the researchers.

They broadened the analysis to 17 other cancers based on FDA-approved immunotherapies to calculate the aggregate $7 billion benefit to life-insurance companies from cancer patients’ extended life expectancy. The total cost of immunotherapy for life-insurance policyholders would amount to about $10 billion, and their out-of-pocket expenses would come to $4 billion, the researchers calculate. Even if life insurers covered all of cancer patients’ out-of-pocket costs, they would still benefit from the new therapies by about $3 billion, the researchers find.

Alternatively, if insurers have most of the bargaining power, the researchers suggest that insurance companies could allow policyholders to borrow against their death benefits to pay for therapy, or to reduce the death benefit by the cost of the treatment. Insurers could also offer a loan to cover treatment that would need to be repaid only if the therapy succeeded.

In contrast to various other credit-based proposals out there, allowing patients to borrow against their death benefits is analogous to allowing households to borrow against their home equity in the mortgage market, Koijen and Van Nieuwerburgh argue. The problems they foresee with other credit-based solutions are that “households cannot pledge their future labor income and may default on [traditional] loans received for medical treatment,” and that the risk of lower earnings after treatment reduces borrowing capacity. They believe it makes better sense to unlock the financial potential of life-insurance policies, based on their findings of high rates of policy ownership and average face values well into six figures.

The study suggests that there may be some benefit to integrating life- and health-insurance products, and that in any case, life insurers would gain in reputation from saving lives while increasing life expectancy, lowering the cost of life insurance.

“A virtuous cycle of more life insurance premium revenue, higher life insurance participation rates and coverage, and more payments for treatment would result. A larger drug market would stimulate further development of immunotherapies, accelerating the virtuous cycle,” the researchers conclude.

A study of two multibillion-dollar retail chains homes in on managers.

A Good Boss Can Boost Team Productivity

Economists consider how the technology will affect job prospects, higher education, and inequality.

How Will A.I. Change the Labor Market?

The growth of privately held businesses has some regulators and policy makers pondering whether to push for more financial transparency.

Is the US Economy ‘Going Dark’?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.