Syverson, 2017

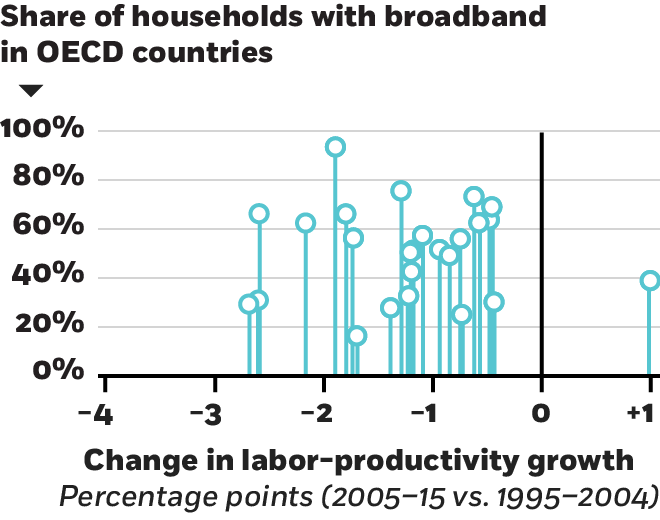

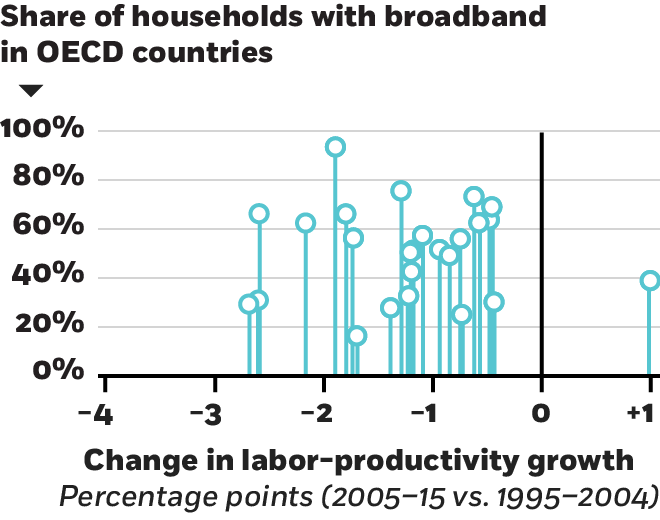

Similarly, if you compare each country’s productivity-growth slowdown to the fraction of households in that country with broadband access, the relationship is again zero.

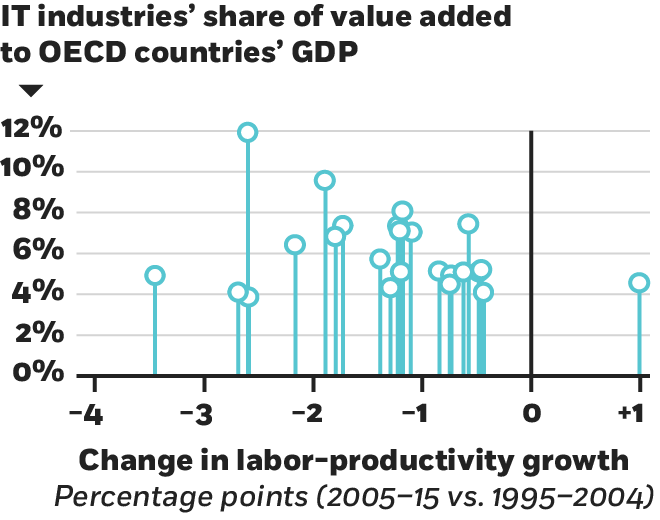

There just does not seem to be any systematic relationship between the size of the slowdown of productivity growth and the importance of IT products in a country’s economy, which is a strike against the mismeasurement hypothesis.

Pricing IT

Next, let’s look at the work of other researchers who have said, “Well, we’ve got a way to get at, through the side door, what the value of these technological goods are.” We can take their methods, put in new data, and see whether we can get a feel for what the value of these IT-related goods might be. There are about a dozen or so carefully done studies that attempt to put a value on technological goods, so do any of them arrive at a value anywhere near $3 trillion?

In short, no. These studies typically produce figures in the neighborhood of $100 billion–$200 billion in the US. That’s not pocket change, but it’s nothing compared to the $3 trillion of output that is missing because productivity growth has slowed. The highest estimate comes from Chicago Booth’s Austan D. Goolsbee and Stanford’s Peter J. Klenow, who calculate that the total consumer valuation for these products might be in the neighborhood of $850 billion. That’s twice as large as the second-largest estimate, but still not even a third of the way to our missing $3 trillion. What’s more, the studies to which I’m referring are estimating the total surplus created by these products—this includes revenues, which are used to calculate GDP, but also consumer surplus, which isn’t.

Implications of mismeasurement

As a third analysis, let’s take the missing $3 trillion at face value and say, “OK, let’s suppose that $3 trillion really does exist, and we just missed it in our statistics.” What would that imply about what’s happened if we did measure it? Let’s wave our magic wand, say we’re not missing that $3 trillion anymore, and then ask ourselves whether we believe those numbers once we’ve added that $3 trillion back in.

According to what we can measure, IT-related industries in the US produced $1.4 trillion in total value added in 2015, the latest year for which data are available. That’s up from $800 billion (adjusted for inflation) in 2004, so we’ve had measured growth in the production of IT-related products in the neighborhood of $600 billion. Now, if we accept that these are the sectors from which this missing $3 trillion is coming, what we’re really saying is that $600 billion is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s another $3 trillion that was being produced but that we missed in our statistics, so the real number isn’t $600 billion, but rather $3.6 trillion.

So we can ask, “All right, do we find it plausible that we have basically captured one-sixth of the output that was actually created in these sectors?” Is our ability to measure output so poor that we actually only capture about 17 percent of the activity in these sectors? That’s the implication of the mismeasurement hypothesis.

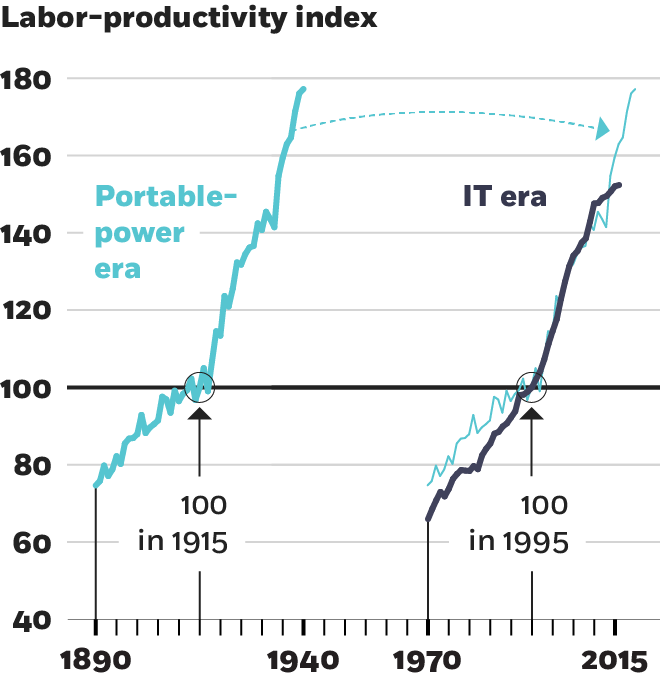

Another implication is that productivity growth in these sectors was really astronomical. As measured, these industries experienced 80 percent labor-productivity growth. In 2015, a worker hour in these IT-related sectors created 80 percent more output than it did in 2004. That’s very rapid growth. But according to the mismeasurement hypothesis, it was actually much faster: 415 percent growth over that 10-year period. Is it plausible that these sectors really experienced this sort of growth, which would be an order of magnitude beyond anything we’ve ever seen in any sector over an extended period of time?

Another way to look at it is that $800 billion was about 8 percent of GDP when the productivity slowdown started. Three trillion dollars is 17 percent of GDP right now. So are we missing 17 percent of GDP from a sector that accounted for 8 percent of GDP when the slowdown started?

I don’t have empirical answers to any of these plausibility questions. But if nothing else, we can say that accepting the mismeasurement hypothesis would require us to swallow some striking figures.

The evidence of income

Finally, let’s look at income versus output. GDP is the total value of all expenditures in the economy. Gross domestic income is the income flip side of that. It’s the total amount of income in the economy. These two things, when you add everything up, should be equal to one another, because one person’s expenditure is another person’s income. But they never do in practice, because they’re measured using different data. The Bureau of Economic Analysis adds both measures up, and they’re close, but they’re never the same.

If you look at the gap between them, there’s actually a pattern to it. Since 2004, gross domestic income has been higher on average than GDP by about 0.5 percent per year. If you add up all those differences across the decade, the decade covering the productivity slowdown, it adds up to almost $1 trillion. In some sense we’re saying there’s $1 trillion of income that has been earned over the last decade that isn’t showing up in expenditures.