Why Hasn’t Technology Sped Up Productivity?

Slow productivity growth is costly. There’s cause for hope.

Why Hasn’t Technology Sped Up Productivity?Even as artificial intelligence crosses unlikely thresholds and spurs stock prices, it isn’t having a discernible effect on the economy. Measured productivity has been declining for more than a decade in the United States and abroad. It calls to mind Solow’s paradox, a 1987 observation by the Nobel laureate economist Robert Solow, who noted that one “can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the same thing is happening with artificial intelligence, or AI, according to MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson, MIT PhD candidate Daniel Rock, and Chicago Booth’s Chad Syverson. AI is a once-in-a-lifetime, general-purpose technology that promises to provide an “engine of growth,” they write. This was also true of the steam engine, electricity, and the internal combustion engine.

And yet, the researchers point out, the steam technologies that drove the US industrial revolution took nearly 50 years to show up in rising productivity statistics. And the first 25 years after the development of the electric motor and internal combustion engine were associated with a productivity slump, with growth of less than 1.5 percent a year. Then in 1915, the pace of economic expansion doubled for 10 years.

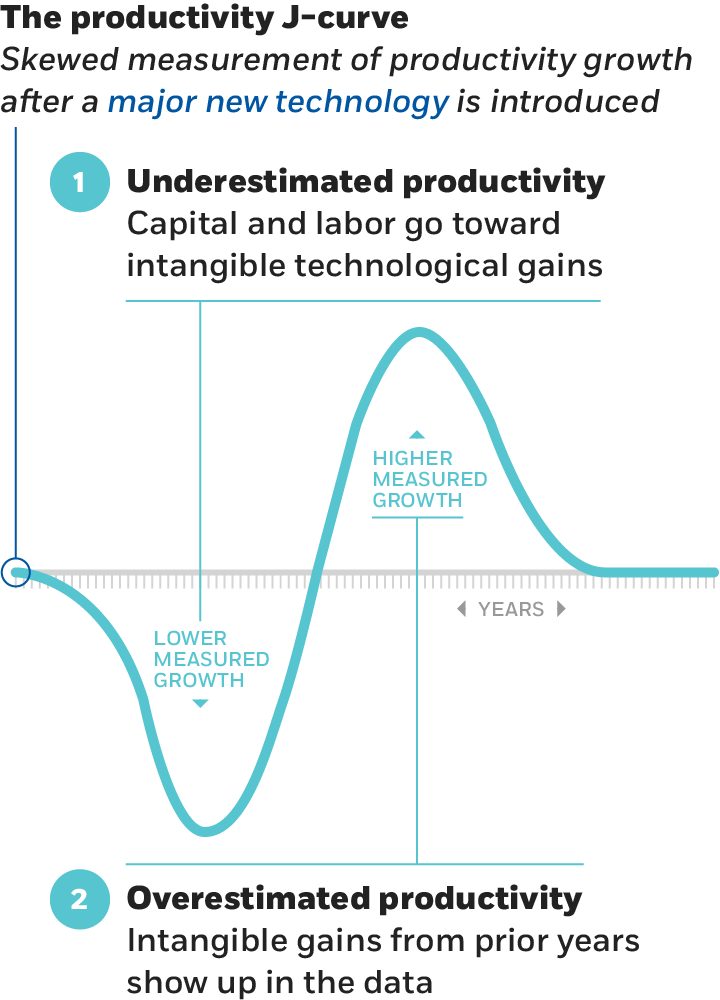

In these cases, the researchers find signs of what they call “the productivity J-curve,” a period in economic data when productivity growth is underestimated, followed by a period when it’s overestimated. This dynamic may have also applied to the computer-powered information-technology era, with 25 years of slow productivity growth followed by a decadelong acceleration, from 1995 through 2005.

The shape of a measurement error

The researchers suggest that some investments in AI will take time to appear in measured productivity statistics.

Brynjolfsson et al., 2018

Why does this happen? It takes a while for businesses and workers to figure out how to harness innovative new technologies. It also requires investments in intangible developments, including “a fundamental rethinking of the organization of production itself,” the researchers find.

“Along with installing more easily measured items like physical equipment and structures capital, firms must create new business processes, develop managerial experience, train workers, patch software and build other intangibles,” the researchers write. The intangible investments associated with bringing out the potential of AI thus aren’t yet showing up in economic growth data, they argue.

The productivity J-curve is really an error in measuring total factor productivity, one of the main elements of GDP, the researchers write. The error results in an initial dip in measured productivity “while the investment rate in unmeasured capital is larger than the investment rate in other types of capital,” they find. Measured productivity then rises “as growing intangible stocks begin to affect measured production.”

Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson developed a model, based on stock-market valuations that capture the magnitude of intangible investment value, to account for this measurement error. They used the model to estimate the value of intangible capital investments and demonstrate how their estimates can be used to infer more-accurate, timelier measures of total-factor-productivity growth.

Slow productivity growth is costly. There’s cause for hope.

Why Hasn’t Technology Sped Up Productivity?The economy is early in the AI adoption wave, with start-up funding for AI having increased from $500 million in 2010 to $4 billion in 2016. According to the researchers, this implies intangible investments in AI may have accounted for 0.55 percent of “lost” output—or output that national productivity statistics didn’t measure—in 2017.

Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson suggest that investments in AI are likely to grow rapidly and that the US economy may be entering a period when AI will have significant effects on estimates of productivity growth. An arrival of the benefits of intangible investments in AI over the coming decades would expectedly cause a productivity surge, the researchers find.

If some suppliers are innovating at a much faster pace than others, it can hinder an industry’s growth.

The Equation: Are Supply Chains Holding Back Productivity Growth?

In Denmark, those who picked education benefits over disability payments got back to work within seven years, and with a 25 percent raise.

College Bests Benefits for Injured Workers

The problem is larger than previously calculated.

Savvy Refinancers Reinforce Mortgage-Market InequalityYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.