Who Does Raghuram Rajan Blame for Inflation?

The former governor of the Reserve Bank of India discusses the Fed’s role in the US economy and analyzes its response to the pandemic.

Who Does Raghuram Rajan Blame for Inflation?As the coronavirus pandemic brings the US economy to a halt, the housing market shows every sign of freezing up too. And if house prices drop, retail prices will follow, according to NYU’s Johannes Stroebel and Chicago Booth’s Joseph S. Vavra.

For every $1 that home values fall in an area, prices of everyday products in neighborhood grocery and drug stores could decline by 15–20 cents as property owners feel less wealthy and devote more energy to penny-pinching, the research suggests. This is likely to compound the effects of soaring unemployment and plunging business activity, adding to policy makers’ concerns about deflationary pressures.

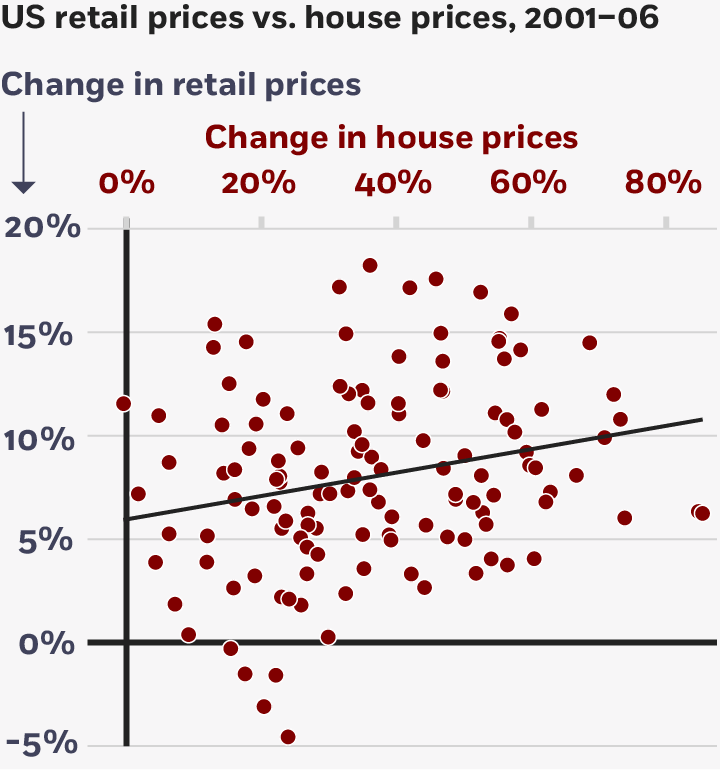

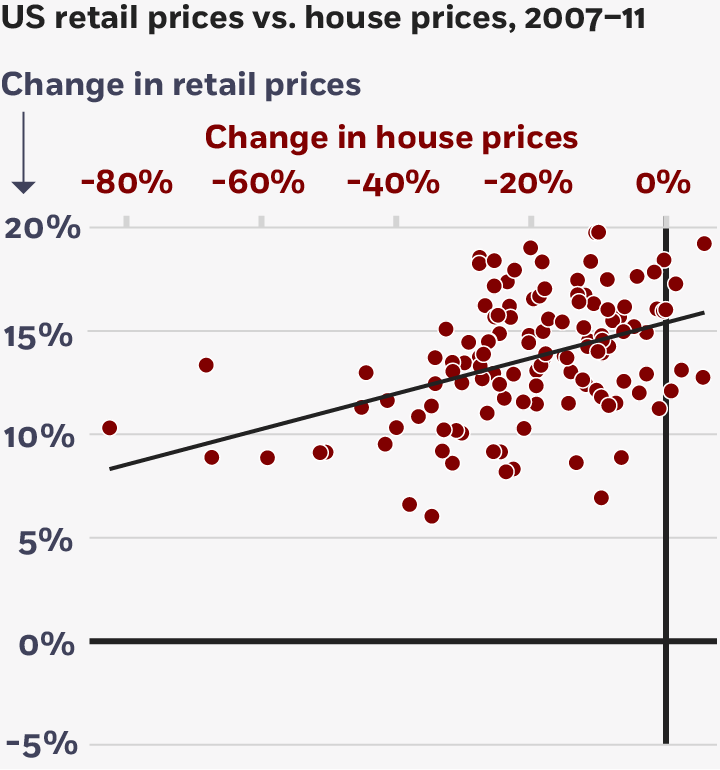

Research finds that retail prices trended upward during the boom years of 2001–06 in areas where housing prices surged. And retail-price increases were more pronounced during 2007–11 in areas where the housing bust was not as bad.

Stroebel and Vavra, 2019

Stroebel and Vavra studied movements of local housing prices and local retail prices from 2001 through 2011, covering the period before, during, and right after the Great Recession. Tapping the Nielsen Datasets at Booth’s Kilts Center for Marketing, they used bar-code-level price data from 2,400 US zip codes on a variety of products in 31 categories, mostly items found in grocery and drug stores. They lined up the findings with housing-market data by zip code.

The researchers find that through boom and bust, retailers adjusted their markups on wholesale costs upward and downward on the basis of consumer shopping behavior. Consumers’ focus on what they paid for goods waned as they felt wealthier in a booming real-estate market, and grew more intense as housing values crashed.

The 15–20 percent impact on retail prices “is highly significant,” the researchers write. “Its magnitude implies that house price–induced local demand shocks account for roughly two-thirds of the substantial inflation differences across regions.”

Stroebel and Vavra caution that this effect appeared only in areas with high rates of homeownership. Rising or falling property values didn’t have the same effect on renters.

“Our research has direct implications for understanding the consequences of housing booms and busts,” Vavra says. “We’ve shown that in addition to the well-documented effects of house prices on spending, there are also important effects on local prices.”

Johannes Stroebel and Joseph S. Vavra, “House Prices, Local Demand, and Retail Prices,” Journal of Political Economy, June 2019.

The former governor of the Reserve Bank of India discusses the Fed’s role in the US economy and analyzes its response to the pandemic.

Who Does Raghuram Rajan Blame for Inflation?

A study of demolitions in Chicago finds they raised housing costs, hurting renters.

Infographic: How Demolishing Public Housing Increased Inequality

Luigi Zingales and Tyler Cowen debate the price of tech giants’ dominance.

Should We Care If Google Is a Monopoly?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.