Networking Differently Could Increase Your Salary

It’s fine to accumulate contacts, but notice how you network.

Networking Differently Could Increase Your Salary

Sebastien Thibault

In Zhejiang, a province just south of Shanghai on China’s east coast, two brothers launched a textile business, hoping to take advantage of the region’s affordable, well-trained labor pool. They used their family savings to start their business. But neither brother had industry experience, and sales were slow.

Then one of the brothers sent a son to the Middle East, on a trip that they hoped would help them spot trends and better understand the competition. While there, the son met with an old friend who specialized in marketing and offered some recommendations for how to expand sales channels. Spurred by the friend’s advice, the textile business set up subsidiaries across the Middle East—and prospered.

Given the brothers’ lack of experience and the company’s sluggish start, the reversal of fortune may appear to be an aberration. But its success fits a pattern emerging from entrepreneurship research.

For those who make their living recognizing winning start-ups—such as the venture-capital firms of Silicon Valley—the perpetual search for the next big thing may include considering a start-up’s business model and management, its market, any referrals, and quantitative analysis, among other things. But anyone trying to spot a successful start-up, or to build one, can glean some tips from a long-term study that includes the Zhejiang textile company and hundreds of other ventures in China’s Yangtze River Delta. The findings from this and other studies highlight how entrepreneurial networks in China share important traits with those in other countries—and how the Chinese networks could hold some lessons for entrepreneurs the world over.

Networks are a topic well known in start-up circles, and in sociology. For the past four decades, researchers have been studying social networks to figure out, among other things, what in a network gives some people an advantage over others. They have looked at the importance of strong versus weak contacts, and at who is connected and what is to be gained by bridging gaps between different clusters of people. Most of these studies have been conducted in the United States and Europe.

China’s history of formal entrepreneurship is relatively short, making the country an unlikely place to study start-ups. Though Chinese citizens have long tried to accumulate extra income, for many years there was a gray area when it came to launching private enterprise in the country. But in 2004, China adopted a constitutional amendment that said private enterprise was as important as state enterprise. Two years later, Lund University’s Sonja Opper and Cornell University’s Victor Nee began gathering data about 700 entrepreneurs from in and around Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Nanjing, areas that collectively make up a fifth of the country’s GDP. The researchers interviewed company founders every three years to learn about their key contacts and family members. They tracked changes in social ties as the new businesses grew and experienced significant events.

It’s fine to accumulate contacts, but notice how you network.

Networking Differently Could Increase Your Salary

Two researchers craft a more detailed picture, not simply of female entrepreneurs, but of a variety of women who move in and out of the labor market at various points in their careers.

Breaking Stereotypes about Female EntrepreneursThe original focus of the data collection was on CEO and company data. Because 80 percent of the company founders interviewed are still with their companies, a higher percentage than is typically seen in the US or Europe, the Chinese data provide particular insight into what it takes to get a venture off the ground, says Opper.

But in addition, the data lent themselves to the study of networks, which attracted Chicago Booth’s Ronald S. Burt, a sociologist who provided the network instrument and analysis for the 2012 survey. Because the Chinese companies don’t have much external support from banks, the government, or venture capitalists, researchers can more clearly decipher initial business decisions and ties. “We looked at how these entrepreneurs built up their support system,” Burt says. By applying social frameworks devised from his earlier US and European research, he and his coresearchers make several findings that would seem to apply globally.

Most entrepreneurs see value in having a wide range of contacts they can call on when building a business. Chinese entrepreneurs, just like their Western counterparts, can avidly collect business cards and LinkedIn contacts. But some connections and contacts are particularly helpful, and according to the Chinese data, business owners obtain significant value from their most-trusted ties, especially from people they’ve known for a long time and those who are somehow unbound from other people in the owners’ networks.

Guanxi, a traditional Chinese concept, refers to longtime acquaintances who have a relationship defined by intimacy, obligation, and a high level of trust. In a business context, the guanxi are a family-like, deeply trusted circle of people who can help grow a business—as opposed to a larger, more professional network where trust and longstanding relationships are not necessarily always present. A guanxi network, says Burt, shares some similarities to what in the US is called the “old boys’ club.”

Early on, trusted contacts matter

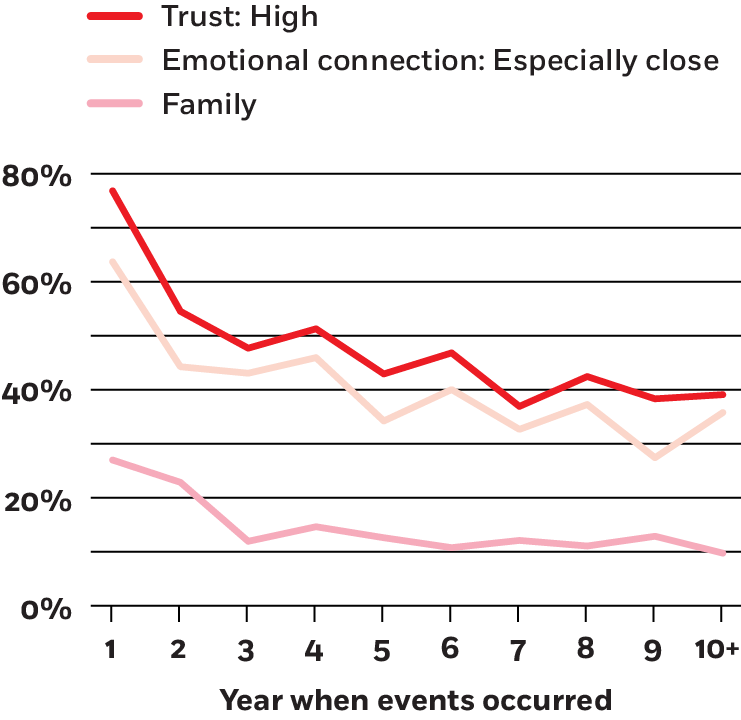

Chinese entrepreneurs’ reflections on milestone events in their business’s history suggest that establishing a loose network of highly trusted contacts is important for success.

Length of entrepreneurs’ relationship with key contacts who helped at significant moments in business’s history

Number of years

Entrepreneurs’ relationship with key contacts who helped at significant moments in business’s history

Share of contacts cited with each characterization

Burt and Opper, 2017; International Association for Chinese Management Research

The networks are alike in that when one member of the network is in trouble, other people in that network can lose face. And while guanxi is a neutral term, it too can be characterized by negative or unethical behaviors, just like the old boys’ club, which for many people carries negative connotations associated with excluding people who don’t fit a particular description.

In China, intricate guanxi networks play an important role in business, providing the kind of support that formal institutions offer elsewhere. In a study by Burt and Katarzyna Burzynska of Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands, two-thirds of participants’ most-important contacts qualified as guanxi, as the researchers defined it.

These relationships can help give entrepreneurs an edge during critical moments, by forming a bridge to other networks, according to the research. Say a businesswoman turns to guanxi to get an electronics business off the ground. She may turn to a computer wholesaler she knows, who may provide support in the form of product supply, but also, crucially, information. Tapping a family-like contact at a key point could help the entrepreneur form ties to and acquire valuable knowledge from other networks, through a behavior sociologists call “brokerage.”

“Much of an entrepreneur’s brokerage potential lies beyond his or her current network—in strong, trusting connections with people who helped the entrepreneur through a significant business event,” they write.

One guanxi contact is not enough. Say the founder of the electronics business turns first to a longtime contact to be a supplier, but then to another guanxi contact to provide the first international contract. In the process, she creates a core network of trusted individuals who can help the business succeed.

Entrepreneurs who turned to two loosely connected people rather than just one contact to successfully deal with their first two significant events were more likely to succeed, the researchers find. In the case of the Zhejiang textile company, the founder’s son’s friend provided access to information, and then funding for expansion came from another guanxi contact, a former neighbor who ran a bank.

People who were the most helpful were often the people the entrepreneurs had known the longest—but were usually not family.

Moreover, these individuals can help the founder tackle challenges that could sink a business, particularly early on. The researchers were surprised by the importance of early milestones and the way founders used their networks to, for example, secure equipment or tax advice. Researchers call these associates “event contacts,” as they help steer founders through events rather than day-to-day operations.

Disparate-yet-trusted contacts allow company founders to create weak ties across their business networks, which increases the chances of success when these contacts are deployed during these early milestones, according to Burt and Opper. “Those entrepreneurs had two or more mutually supportive contacts in their core network, one helpful at founding and the other helpful with the first significant event.”

People who helped a company early on acquired lasting importance. When Chinese entrepreneurs were interviewed in 2012, they identified people who had been valuable to their business dealings. A person who helped an entrepreneur jump-start a business, perhaps by securing her first overseas contract, typically appeared on her list of contacts in every interview.

People who were the most helpful were often the people the entrepreneurs had known the longest—but were usually not family. That’s an important distinction, as many scholars say that family is the origin of many Chinese ventures. Although family is often one source of early help, longstanding relations beyond the family are the more usual source. Ultimately, “entrepreneurs see all of their relations with event contacts as guanxi ties,” the researchers write.

How applicable are lessons learned in China to entrepreneurs outside of the country? Very, say the researchers, who observe in Chinese entrepreneurs some of the same trends and behaviors they’ve documented elsewhere.

For example, some entrepreneurs face what sociologists call “character assassination,” where a person is disparaged by his business contacts. Burt’s previous research—which studied European and American managers—suggests that people who limit themselves to close-knit groups are more likely to badmouth colleagues. In that research, entrepreneurs who made a connection with a key contact in a close-knit group, but who themselves were outside of that group, were most prone to being treated as a source of difficulty, which was attributed to the entrepreneur’s character rather than competence. Additionally, people who complained about others in the confines of a close-knit group also found validation through a type of supportive gossip that sometimes encouraged even more badmouthing. More recently, Burt and Tsinghua University’s Jar-Der Luo find identical behaviors in Chinese networks.

There’s also evidence of guanxi in countries other than China. As part of their study, Burt and Burzynska reanalyzed some research Burt had previously conducted at a large US-based financial organization and say there were elements of guanxi among analysts and bankers. Banking can be a tumultuous field, and few relationships in that study lasted two years or longer, but those that did met the researchers’ criteria for guanxi. Although just 10 percent of the bankers’ relationships—versus two-thirds in China—qualified as guanxi, analysts and bankers in the financial organization turned to guanxi-type connections during critical times of growing a business.

Opper is now comparing Chinese entrepreneurs to Swedish ones. Shanghai and southern Sweden are roughly 7,700 kilometers away from each other, and look in many ways like very different places. But according to Opper, both regions were late adopters of entrepreneurship. While Shanghai is a major financial center, many people there were long focused on state-owned rather than private enterprise. And until the mid-2000s, Swedish entrepreneurship was centered in Stockholm rather than the country’s industrial south. Ventures in both countries are used to a significant amount of government support. To dig more deeply into how early networks affect later success, Burt and Opper have a more-detailed China survey going into the field this fall.

The VC industry continues to pay lip service to diversity.

Women and Minority Investors Are Taking Matters into Their Own Hands

Successful business pitches still need to focus on a few things.

COVID-19 Isn’t Changing What Investors Want

Four insights from Chicago Booth’s Waverly Deutsch for entrepreneurs hoping to cultivate scalable success.

How to Start-UpYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.