The Power of Your Pivot Point

To survive opening stumbles, entrepreneurs need an objective measurement around which their business-plan numbers revolve.

The Power of Your Pivot Point

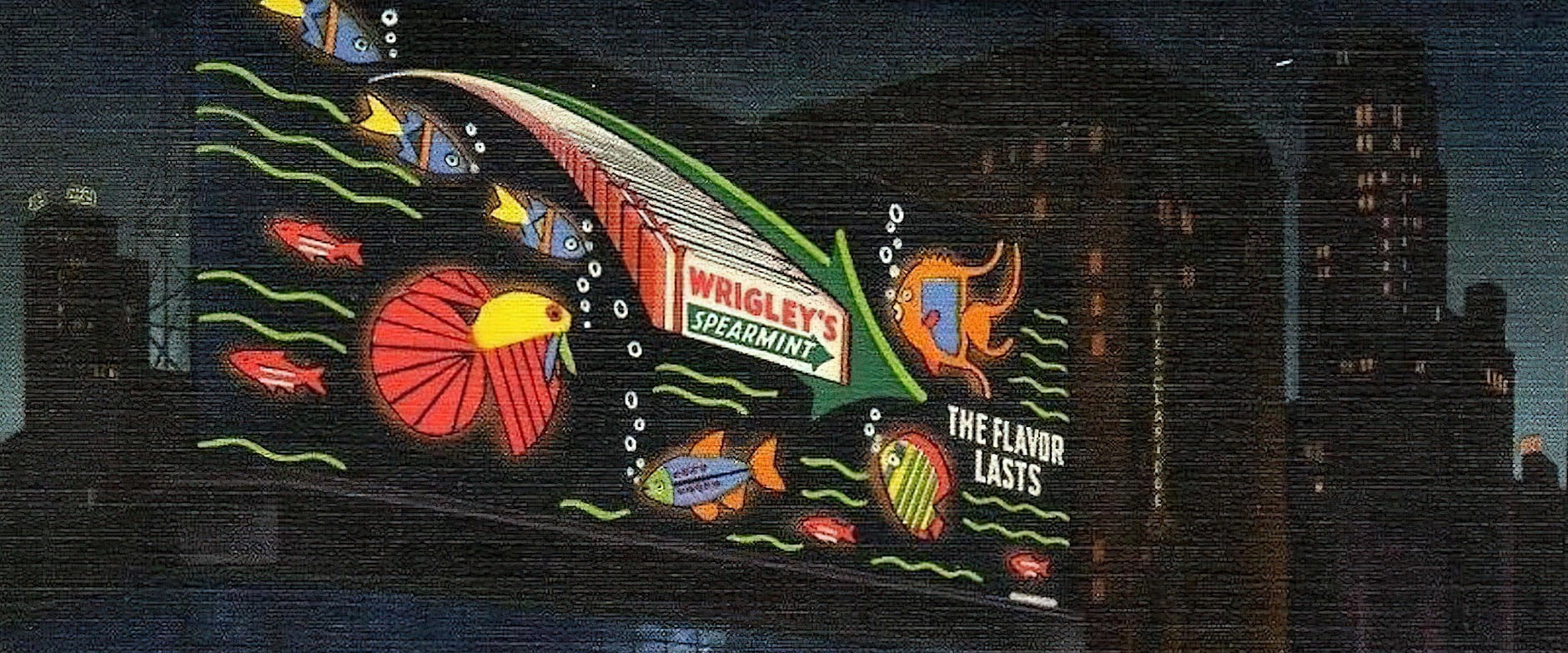

Alamy

William Wrigley Jr. spent many of his childhood years selling his father’s Wrigley’s Scouring Soap on the streets of Philadelphia. So when he set out for Chicago in the 1890s, Wrigley did what he knew and brought the soap trade with him.

Had Wrigley stuck to his original plan, it’s unlikely his name would stand today as one of the most iconic in Chicago business history. Instead, he took some calculated risks and pivoted his business twice.

Wrigley had been tossing in packages of baking powder as an incentive for purchasing his soap. When the baking powder proved more popular with customers than his soap, he made it his main product. Soon he realized that his new bonus product, chewing gum, was an even bigger draw, and he changed his focus again. The rest is history.

Despite evidence that pivots can improve productivity and competitiveness, businesses aren’t always eager to make changes. It’s difficult to consider experimenting with a business model that has worked in the past, and many small-business entrepreneurs may not feel as though they have the time and resources to do so.

I along with colleagues from Stanford and the London School of Economics and Political Science wanted to see if we could not only induce pivots, but show how well they could work. We connected more than 500 business owners in Uganda with remote business coaches, who talked for an hour every two weeks through Skype. We compared them with a similar number of entrepreneurs who did not receive coaching.

Conversations during the coaching sessions tended to focus on product economics and competition, or how materials or equipment could be repurposed. The coaches encouraged business owners to assess the preferences of customers to see if their needs still aligned with the business’s products or services.

To survive opening stumbles, entrepreneurs need an objective measurement around which their business-plan numbers revolve.

The Power of Your Pivot Point

It’s possible to grow that fast, but wildly optimistic to bet on it.

The Elusive Hockey-Stick Sales CurveA woman who ran a clothing store stands out as a prime example of how the coaching worked. Her business was successful, but in talking with customers, she realized they were far more interested in the fashion advice that she gave than the products she sold. It turns out that fashion consulting was the woman’s passion, and her resulting pivot not only made her much happier and her business more profitable, but also met a need she didn’t realize her customers had.

Those who received coaching were 63 percent more likely to have pivoted or shifted their marketing strategies than business owners who didn’t participate. The coached entrepreneurs also increased monthly sales by more than 27 percent.

The study was done in Uganda, but the findings are fairly universal. Coaching offered a market context from an outsider with a different perspective. That can benefit businesses anywhere.

It doesn’t have to be formal or expensive. Small-business owners can get guidance by surveying their own customers, talking with business-minded friends, or reaching out to peers in industry-specific organizations.

And remember: before Wrigley stamped his name on Chicago history, he had to be willing to tweak his business model and switch from baking powder to gum.

Pradeep K. Chintagunta is the Joseph T. and Bernice S. Lewis Distinguished Service Professor of Marketing at Chicago Booth.

This column is part of the Chicago Booth Insights series, a partnership with Crain’s Chicago Business, in which Booth faculty offer advice for small businesses and entrepreneurs on the basis of their research.

The VC industry continues to pay lip service to diversity.

Women and Minority Investors Are Taking Matters into Their Own Hands

Successful business pitches still need to focus on a few things.

COVID-19 Isn’t Changing What Investors Want

Science sheds light on the importance of familiarity.

What Venture Capitalists Can Learn from ‘Racist’ RatsYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.