How to Set a Better Budget

Accounting for atypical costs such as car repairs and medical bills can make consumers’ spending estimates more accurate.

How to Set a Better BudgetIf you’re out in the cold, you might crave being around your closest friends and family; the very thought of being around them may warm you up. Research by National University of Singapore’s Yan Zhang and Chicago Booth’s Jane L. Risen explains why.

As advanced as the brain is, it makes some surprisingly quirky assumptions about the world. For one thing, it assigns physical descriptions to psychological sensations, which is why we can have a “smooth” social interaction or a “weighty” conversation.

Moreover, people’s physical states can influence how they perceive something such as a social interaction. If a person is holding a heavy object, she may perceive a conversation as more “weighty.” If another person is asked to seal his feelings in an envelope, he may enjoy a sense of psychological “closure.” Psychologists call this phenomenon “embodiment.”

Zhang and Risen set out to address another piece of the puzzle: Do people in a particular physical state seek out balance through their psychological state, and vice versa? And if so, why? In a cold environment, do people seek out a warm social interaction to counter the chill? And if you’re about to head into a socially chilly business meeting, do you compensate by grabbing a cup of hot coffee or tea on the way?

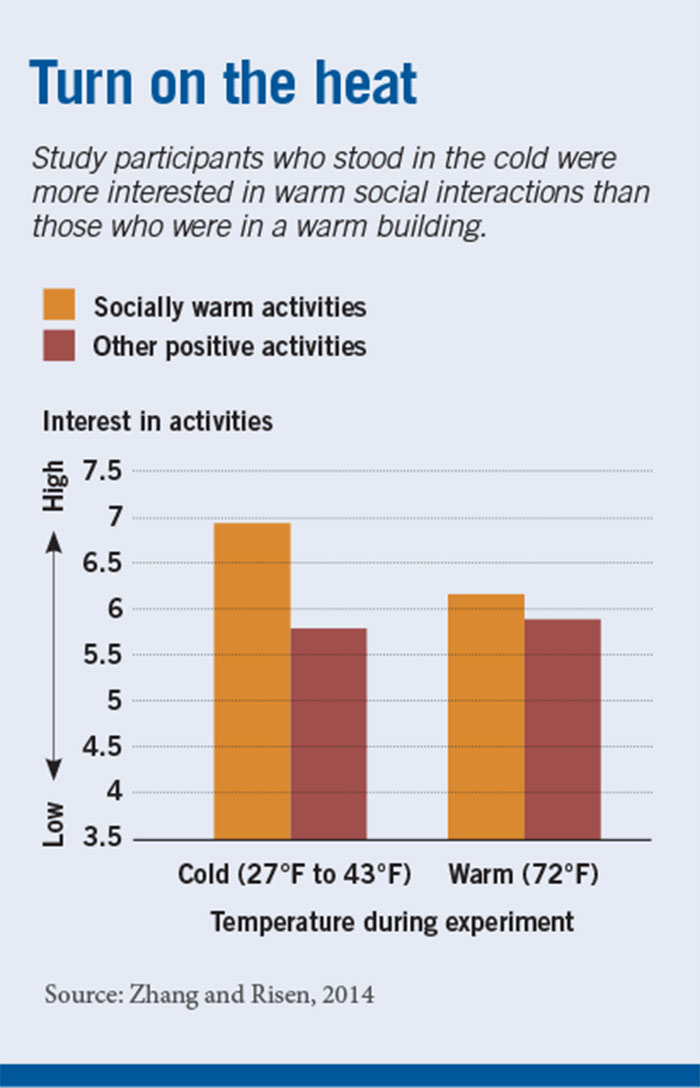

To find out, Zhang and Risen put people in different physical environments—in a warm building, or outside in Chicago’s blustery winter weather—and observed what kinds of social activities were more appealing to them as a result. Participants who were chilled preferred communal activities such as having dinner with a loved one over more solitary activities such as listening to an interesting lecture. “We find that people who stand in the cold are particularly interested in socially warm activities but not in positive activities that are not socially warm,” says Risen.

The team looked into the cognitive mechanism that might explain this and found several patterns: when people are primed with the goal of reducing their physical coldness, they seek out warm social interactions; but when they are simply primed with the concept of cold, they are not particularly interested in those warming activities. This suggests that people desire social warmth when experiencing physical coldness because they have an active goal to feel less cold. If they have a different goal, the desire should go away. Indeed, when given alternate goals such as thinking about what activities would make them happy rather than warm in cold weather, people exhibit much less interest in warm social interactions.

The researchers flipped the phenomenon with similar results: people who were asked to remember a time when they felt socially excluded craved warm items, like a hot cup of coffee. “Again, this preference is reduced when we activate an alternative goal other than reducing social coldness,” says Risen.

Earlier research, by Tristen K. Inagaki and Naomi I. Eisenberger of UCLA, indicates that the same brain mechanisms underlie the feelings of physical warmth and social warmth. Risen and Zhang’s research supports this finding, since it shows that we crave warm social interactions when we’re cold, but not when we’re primed with other, non-temperature-related goals.

Accounting for atypical costs such as car repairs and medical bills can make consumers’ spending estimates more accurate.

How to Set a Better Budget

The number of words in news stories and official accounts can reflect the writers’ stereotypes and biases.

The Length of a Police Report Can Be Revealing

An excerpt from the updated edition of the bestselling book.

Nudge: Preface to the Final EditionYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.