Your Spending Habits Are All in Your Head

Consumers do some complicated mental accounting when allocating money, and researchers are mapping it.

Your Spending Habits Are All in Your HeadThe voice-over says quietly, “You know when you feel the weight of sadness,” as a threatening cloud dumps rain on a character crawling across the bottom of the television screen. As cartoonish as this advertisement (for Pfizer’s Zoloft) may seem, research suggests that TV drug advertising increases sales—not only for the promoted drug, but for its competitors as well.

In the United States, drug manufacturers rely heavily on ads to expand their customer base. Research by Chicago Booth’s Bradley Shapiro finds that when a pharmaceutical company increases its advertising for a drug, firms that sell rival medications advertise less, acting like free riders. That’s because drug ads boost demand for the entire category of medications for the same condition. A viewer often identifies with the general health issue but is apt to forget the name of the specific drug advertised, Shapiro explains, leaving the person’s doctor to choose what to prescribe.

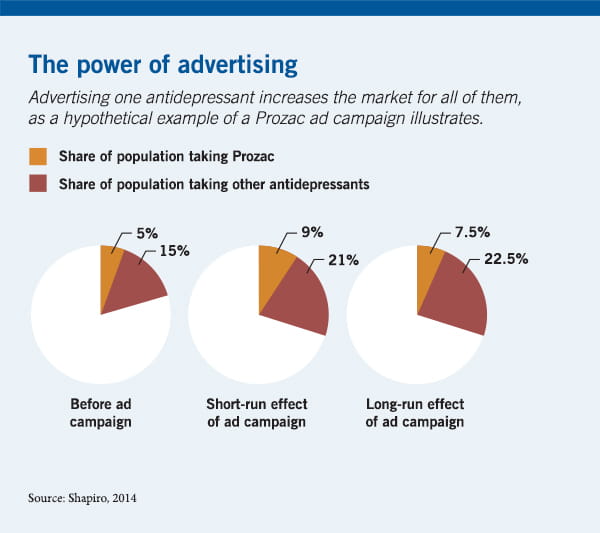

Imagine that 20 percent of people take antidepressants, and that Eli Lilly’s branded drug Prozac has 25 percent of the market, so 5 percent of the population takes Prozac. Lilly runs an ad campaign for Prozac, which increases sales of both Prozac and of antidepressants in general, leading to 30 percent of people taking either Prozac or a competitor.

In the short run, Prozac’s share of the antidepressant market rises to 30 percent. Now, 9 percent of people take Prozac. But that effect dissipates quickly, Shapiro explains. In the long run, Prozac’s market share may fall back to 25 percent. But thanks to the advertising, the overall market for antidepressants has expanded—with Prozac’s share translating to 7.5 percent of the population. “There is a sustained effect on Prozac, but it is only coming through the effect on the category as a whole,” Shapiro says.

In his study, Shapiro examines prescription sales and advertising data, focusing on the borders of local advertising markets, where one household is likely to see different drug commercials from those seen by other nearby households that happen to be in another market.

If rising sales of Pfizer’s Zoloft cause category growth in the long run, why should rival Lilly expand its ad budget? Why not simply free ride on Pfizer’s antidepressant advertising?

Shapiro finds that, up to a point, Lilly can justify its ad budget. Although Pfizer’s ads help sales of both Zoloft and Lilly’s rival drug, Prozac, they help Zoloft sales more. However, his research suggests that there is a point of diminishing returns, beyond which rivals’ advertising makes one’s own incremental advertising less effective.

What if US drug companies were allowed to work together on advertising in a cooperative? This model would eliminate free-rider effects. Companies might produce ads that raise awareness about the symptoms of depression without pitching a particular branded drug, Shapiro says.

He estimates that the companies would advertise four times as much in a cooperative as they do under current conditions, and a co-op could increase the total number of antidepressant prescriptions by 18 percent and profits by 14 percent.

Bradley Shapiro, “Positive Spillovers and Free Riding in Advertising of Prescription Pharmaceuticals: The Case of Antidepressants,” Working paper, October 2014.

Consumers do some complicated mental accounting when allocating money, and researchers are mapping it.

Your Spending Habits Are All in Your Head

Faux journalism can change people's beliefs about a product and affect their spending decisions.

Fake Product News, Posing as Journalism, Draws in Unsuspecting Consumers

Understanding how shoppers search for a product can help businesses more effectively promote their brands.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.