How Do You Get People to Pay to Use a Mobile App?

Research suggests a lesson for developers who want to convert existing users into paid subscribers.

How Do You Get People to Pay to Use a Mobile App?

Michael Byers

The introduction of the price tag was a big step forward for American retailing, and you can thank John Wanamaker. In the 1870s, Wanamaker purchased a former Philadelphia railroad depot and expanded his men’s clothing business to include women’s clothing and dry goods. Along with Macy’s in New York and other department stores popping up in major cities, Wanamaker’s Grand Depot revolutionized how people shopped, primarily by placing many different items under one roof. But it went a step further and changed not only where people purchased items but how they paid. It adopted the price tag.

Until that point, pricing had involved a dance between clerk and customer. When a customer picked up a shirt and admired it, a clerk had to know how much the product cost the store, the overhead associated with storing it, competitors’ prices, and more. Meanwhile, he had to figure out, was the customer in a hurry and willing to pay more, or had he come prepared to negotiate for a steeper discount?

With more than 100 product counters to staff, Wanamaker didn’t have time to teach employees the fine art of haggling. Instead, he affixed a note to every item in the store with the amount a customer was expected to pay. Other stores soon followed suit, and set prices became the norm for most goods and services.

But almost 150 years later, the system could soon revert back to the method that predated Wanamaker’s innovation, in a sense. With online shopping and data collection, companies are moving closer to being able to once again tailor prices to individual customers. Research suggests personalized pricing could raise businesses’ profits considerably, and companies are exploring the idea—but cautiously, wary of upsetting customers.

Thanks to the internet and mobile devices, companies are already collecting large amounts of data and using those to personalize advertisements they offer customers. Pricing is a next step, says Chicago Booth’s Sanjog Misra. “Personalization of these things is already starting to happen,” he says. And while this raises concern among privacy and consumer advocates, he says people may come around to his view, that “information-based pricing or advertising is the right way to go.”

A seemingly simple price tag hides the complicated process of setting prices. A low price with thin margins might attract more customers, but each sale will produce little profit. A higher price may draw fewer customers, but each sale becomes more profitable. The optimal option is often somewhere in the middle: a price high enough to generate profits but low enough to be enticing to a large segment of the customer base. Even then, there will be sacrifices. The seller will lose profits from customers who would have purchased the product or service in question for slightly less—and will sacrifice profits from those customers who would have paid more.

If a seller could charge all customers the highest amount they are willing to pay, it would maximize profits while providing the customers with the products they want or need. This was an advantage of haggling, as individualized prices theoretically benefited both businesses and customers.

Even in the age of the price tag, businesses have sought to balance profits with supply and demand. Airlines, for example, adjust prices based on variables, and two people sitting side by side on a cross-country flight may have paid very different prices depending in part on when they purchased their tickets. From there, it’s not a big leap to move toward more customization. Airlines may use a rewards program or the days and times a person flies to determine whether she is traveling for business. If she comes back on a Friday rather than staying the weekend, for example, she’s probably flying on business—and an expense account. The airline might charge a little more.

And an airline doesn’t have to know much about a person to do that. Imagine what it could charge if it also factored in location, income, credit score, number of dependents, or other available information. Many of these data points could be used to suss out how much people will pay for given goods and services.

Economists are intrigued by this idea. And one company’s experience hints at the potential that personalized pricing could have for profits.

ZipRecruiter, which calls itself the fastest-growing online employment marketplace in the United States, was, typically, attached to the price tag. The privately held company charges a monthly fee to businesses that want to simplify and accelerate the process of finding and screening candidates for jobs. It posts notices of openings on hundreds of job boards, uses a machine-learning algorithm to identify qualified candidates, and encourages these candidates to apply.

In 2015, the company was still a smallish start-up that had purchased a company where Booth’s Misra had worked. After the acquisition, over coffee, Misra and the company’s COO, Jeff Zwelling, were chatting about prices. At that point, ZipRecruiter charged employers $99 a month, for all levels of services. The amount—which “matched the reach and level of technological sophistication we were offering at the time,” says ZipRecruiter’s CEO Ian Siegel—seemed palatable to customers and earned the company a profit, but Misra’s gut reaction was that $99 a month couldn’t possibly be the best price for all ZipRecruiter customers.

“These companies have incredible human capital for technology, supply chain, and logistics,” says Chicago Booth’s Jean-Pierre Dubé—but they find it difficult to process and internalize opportunity costs when it comes to pricing. Misra sensed that raising prices had a lot of upside potential, and ZipRecruiter was open to experimenting.

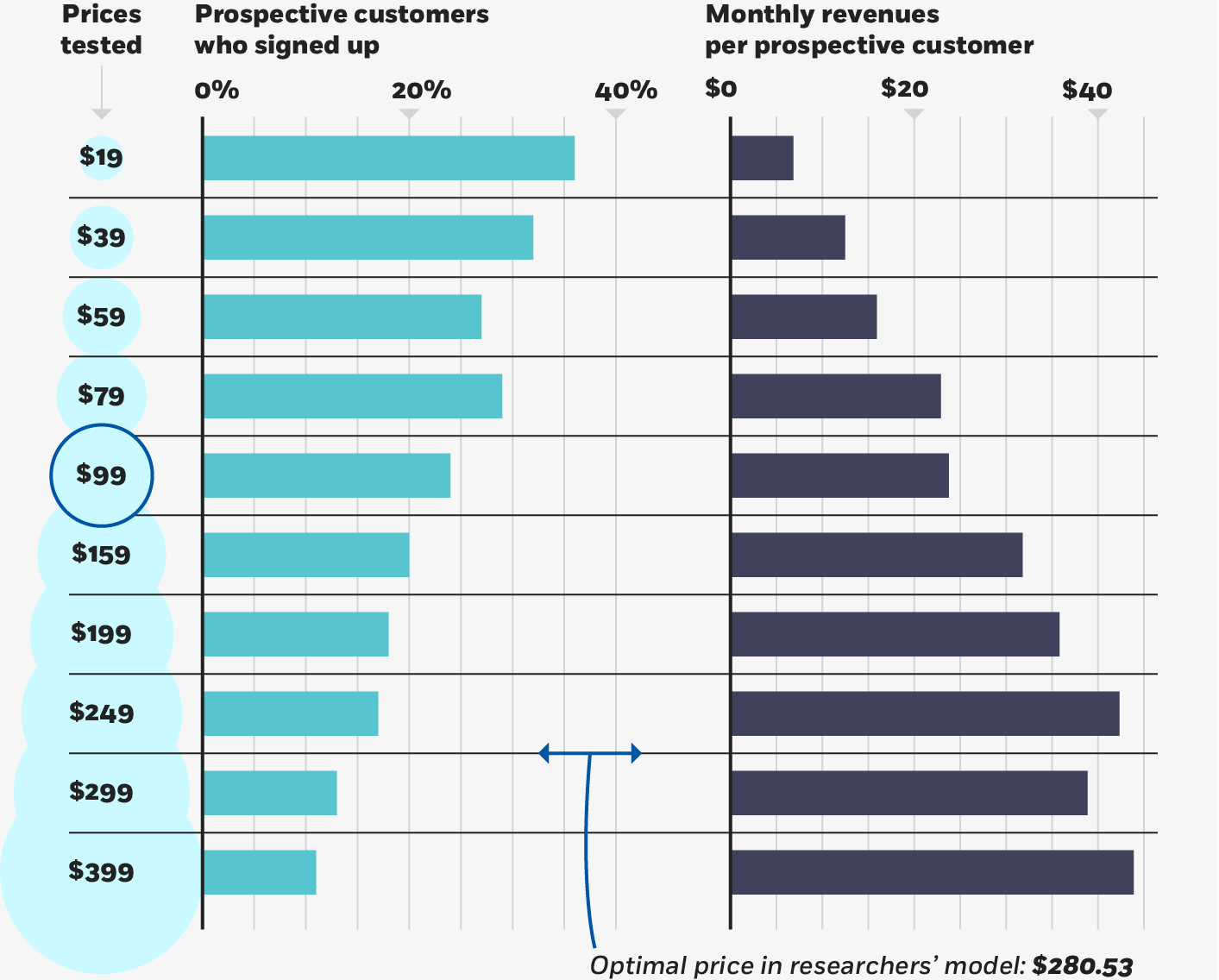

The company agreed to work with Misra and Dubé to run a two-part experiment. For one month, in September 2015, new customers coming to ZipRecruiter’s website weren’t charged the standard $99. Instead, they were randomly assigned monthly prices ranging from $19 to $399.

The company asked new customers for a lot of information about their businesses—including the location, company type, and benefits offered. This was all information that could theoretically be used to figure out how much individual customers would be willing to pay. So in a second month of the experiment, some new customers were assigned monthly prices that an algorithm generated specifically for them, ranging from $142 to $399.

In the first month, the researchers observed, doubling the price from $99 to $199 resulted in some customer loss: a quarter of customers whom the company surmised probably would have paid the $99 price declined to subscribe at the higher price. But because every customer brought in more profits, revenues still increased 14 percent, which suggested to the researchers that ZipRecruiter had been undercharging. The results indicated that ZipRecruiter could increase profits by moving to a higher price, and the researchers calculated that the optimal price was between $249 and $399.

But the results also suggested that ZipRecruiter could refine its pricing even further by using the data it collected to determine a maximum price each customer was willing to pay. In the second month—which compared the standard, optimal, and targeted prices—profits increased 84 percent relative to the $99 price. Following the experiment, Misra became an advisor to ZipRecruiter. Dubé has had no business relationship with the company.

In search of the ideal price

Testing a range of introductory prices for online job board ZipRecruiter, the researchers find that the company could have more than doubled its standard price of $99, increasing revenues despite the smaller number of customers willing to pay more.

Dubé and Misra, 2017

This experiment is as close as any company has likely come to charging personalized prices. David Reiley, principal scientist at Pandora and an adjunct professor in the School of Information at the University of California at Berkeley, says companies often run experiments that seek to confirm their own strategies but fall prey to believing correlation is causation. Take experiments involving advertising, for example. “Advertisers may target groups of customers they think are likely to buy their product. Then when they compare people who got an ad to people who didn’t get an ad, they see that the people who got the ad bought more, and they attribute the entire difference to the ad,” Reiley says. “This despite knowing that they are deliberately targeting people who are likely to buy more even in the absence of the ad.”

The ZipRecruiter experiment, by contrast, utilized a significant amount of customer data—doing what economists have long dreamed of but have not had the opportunity to test. “This is pretty amazing work,” Reiley says. “It’s the kind of thing that I’ve advocated for years, but have never seen it done before.”

Despite the promise of personalized prices, it is likely that many companies will be slow to adopt them, the researchers say. Even ZipRecruiter, having seen the findings, ended up not implementing them—and the reasons help illustrate some of the hurdles.

In general, executives can be reluctant to test new prices, says Reiley. “A lot of decision makers would rather act like they know what’s optimal rather than find out what’s optimal. If you’re making decisions at a firm and you decide to do an experiment, you have to admit that you don’t know the right thing to do.” If a pricing experiment doesn’t work, it’s been a waste of time and has risked upsetting customers. If a pricing experiment does work, it suggests that decisions that led to the original price were wrong. Then “the question becomes: ‘Why were you doing the wrong thing this whole time?’”

Watch: Is personalized pricing the future of shopping?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vestibulum blandit vel justo sed accumsan. Nunc et pharetra nulla, non rutrum orci. Nullam eu risus congue, vestibulum lectus sed, pulvinar metus. Pellentesque at mauris eget neque dignissim sollicitudin a eu metus. Quisque hendrerit diam magna, et ornare mi efficitur et. Aenean non pulvinar neque, id pellentesque urna. Sed vitae sagittis arcu. Nunc malesuada purus eu enim maximus, quis mattis enim ullamcorper.

In ZipRecruiter’s case, its executives were willing to try new things, but other practicalities got in the way, including a shift from offering a single product to multiple products. That changed all the numbers, so the researchers’ calculations were no longer applicable. “The one downside to price testing with the scientific rigor we applied is that it takes months for the results to bake,” says Siegel. “After we completed the test, we had a pricing model that was right for the business as it had been, but enough factors in the business changed that the model was no longer valid.” He adds that the insights continue to inform the company’s pricing decisions, however. ZipRecruiter ended up moving to a tiered pricing system.

Also, ZipRecruiter’s competitive landscape changed as Microsoft acquired LinkedIn and Google entered the market. A competitor can quickly undercut a targeted price, says Chicago Booth’s Lars Stole. “Once you start doing this, you’ll have companies in different markets matching those prices. You don’t have much market power.”

Another consideration is that customers could learn to game a system of targeted prices. Software can already tell companies if an online customer has been shopping for similar products on competitors’ websites. Companies, knowing this, could extend a lower price to inspire the shopper to buy. But customers could also use this to their advantage. “If I have browser cookies that make it known I went to Walmart first, well, everyone goes to Walmart first to get a lower price,” Stole says. “Wherever that might happen, companies will know that [I’m shopping for the best deal] and will find it difficult to price discriminate.” In the case of ZipRecruiter, a business could theoretically enter all its information and get a quote, then go back and change a few variables to see how it affects the price. Did that happen? “Not that we are aware of,” says a company spokesperson.

Customers could also arbitrage prices. A savvy consumer targeted with a low price could purchase far more of a product than he needs and sell the surplus to another customer who is being offered a much higher price.

Perhaps the biggest drawback of individualized prices is that they could offend customers’ sense of fairness. Targeted pricing is a degree of price discrimination. While the word discrimination may sound sinister and prejudicial, both second- and third-degree price discrimination are actually fairly commonplace. Sliding prices based on quantity constitute second-degree price discrimination—for example, a buy-two-get-one-free deal, or a company incrementally charging less for each product as more of the products are purchased. Third-degree price discrimination occurs when customers are segmented and charged different prices, such as when senior citizens receive discounts or when prices differ by location.

“What ZipRecruiter implemented in its experiment was third-degree price discrimination—where any two customers who share the same set of characteristics get the same price,” says Misra. “As the set of characteristics grows, this strategy might approach something more akin to first-degree price discrimination, where every customer gets a unique price.”

When companies ignore price

Research suggests that companies could make more money by giving people individual prices. But in some cases, companies are intentionally lowering or capping prices for everyone.

Hurricane Irma provides an example. When Irma battered Florida last year, Floridians reported price surges on bottled water, ice, and lumber, among other products. Demand for these items rose significantly, but the corresponding rise in prices—even if consumers were willing to pay—angered people.

Some companies, including Home Depot, froze prices to avoid the public backlash. But keeping prices artificially low can be just as problematic, says Booth’s Stole.

“If Home Depot doesn’t raise its prices, it runs out of plywood. But if the price rises and is high enough, it incentivizes people from Georgia to load up a truck and bring more plywood to Florida. That doesn’t happen if the price stays low because it won’t be worth the expense to bring that plywood in from another state.”

This may be undisputed in economics, but there are psychological barriers to getting the average consumer to come around to this position.

“Gouging reflects the economic principles of supply and demand but doesn’t meet consumers’ perceptions of fairness,” says Booth’s Fishbach. This perception of fairness “suggests that prices should never go up as a result of increased demand. Prices should go up only if the product is more expensive for the seller, and because products have their ‘true’ price, prices should be similar for different people across different markets.”

Some airlines seemed to defer to this fairness principle as Hurricane Irma approached. American Airlines capped the price of many of its seats at $99 for one-way flights leaving Florida. Others instituted similar caps even though rising demand for their flights could have led to much higher prices.

“These airlines expected their algorithm-based pricing scheme to sell tickets for thousands of dollars because of increased demand,” Fishbach says. But in such situations, “they know they can make a lot of money in the short run but get bad press, and so they choose not to charge what people are willing to pay. Not even close.”

Technically speaking, first-degree price discrimination can’t be implemented. “This requires that we be able to measure exactly what an individual is willing to pay,” which is impossible, Misra explains. But anything approaching first-degree price discrimination can still make consumers feel uneasy.

“Consumers believe there’s an objective and fixed price for any good on the market and it’s not OK to charge anyone, any time, above that fair price,” says Chicago Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach.

That can lead to a public-relations challenge, or nightmare. In 2000, an Amazon customer noticed that when he deleted his cookies, he could buy a DVD he wanted for $4 less. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos said the price difference was part of a company test offering random prices to determine an optimal price for products. He said that no customer demographic information had been used to determine the prices served up. Still, Amazon gave thousands of customers refunds, and Bezos apologized.

This was four years before Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook and six years before Twitter launched. A similar pricing situation today could go viral and lead to hashtag boycotts.

“In markets where prices are transparent and customers can easily figure out what other people are paying, that’s where you run the risk of a backlash,” says Dubé.

A related fairness issue is that people feel uncomfortable about targeting if it’s done in a way that takes advantage of customers. In the days of haggling, buyers and sellers were equally matched, using skill and information to help derive the price. But as data collection has become faster and cheaper, targeted prices derived from thousands of data points put decisions in the sellers’ hands, seemingly tipping the balance of power.

“In general, consumers respond better to differentiated pricing if they feel in control of the process, and if they revisited the purchase they wouldn’t change what they bought,” says MIT’s Catherine Tucker.

And there’s a risk that price discrimination could stray into not just unfair but illegal territory. Say that the parameters used to set prices mean a company ends up charging certain groups more for the same service. Banks are expressly prohibited from discriminating based on race. But what if zip-code data fed into an algorithm served as a proxy for race? The same thing could happen in other industries and algorithms.

“If you don’t put race but you put in zip code, the places where minorities dominate may be treated differently,” Dubé says. If the algorithm finds that companies in zip codes dominated by African American–run companies have a harder time recruiting people than companies elsewhere, it could end up ultimately charging more to African Americans.

Misra argues that the best way to counter this would be for companies to analyze the data to see if they are accidentally discriminating based on race. When he has approached some companies to do this in a research context, he says, the companies have turned him down.

About fairness, Misra and Dubé argue that policy makers, customers, and companies should think more about this. In their view, a single price tag is actually less fair because it restricts the size of the market.

Think of a supermarket owner working to set a single, optimal price for a carton of orange juice. The grocer may know that customers are willing to pay between $2 and $5 for a carton and may choose to charge $4, a point at which a lot of people buy the juice, and close to the maximum amount people might pay. But the price will exclude people who don’t have $4 to spare. There might be people who can only afford $3, and who won’t be able to buy the juice.

The researchers argue that price discrimination expands the size of the market and avoids limiting the people who can access a product or service. Under targeted pricing, they argue, the majority of customers benefit even if a minority of people have to pay more. “No consumer likes to know they paid more than anyone else. But that’s not the only way to look at the fairness debate,” Dubé says.

“The targeting of prices broadens the scope of who is able to pay and brings more people into the marketplace,” says Misra. From the perspective of an economist, this expanded market is good for everyone.

If the price tag represents what’s fair, it is already being compromised. No one expects to pay the sticker price for a car at a dealership, or the same amount as their fellow passengers for an airplane ticket. At colleges and universities, students with means are expected to pay the full cost while others receive what amounts to a discount for the same education. Financial-aid packages are essentially price discrimination. “If we had uniform prices, you could imagine that a lot of poor people would never go to college,” Reiley says.

According to a 2015 report from the National Center for Health Statistics, 8 percent of Americans don’t take medicines as prescribed because of high costs. Some of the most expensive prescription drugs on the market can cost patients more than $70,000 per year. Some customers with financial need can apply for aid or receive discounts on high-priced drugs. But many people are unaware of such discounts, or are unable to secure them. Targeted prices could theoretically bring down the cost of a drug for people who might otherwise be forced to choose between their medication and, say, food.

Tesla, the premium electric-vehicle maker, in 2016 quietly charged varying prices for its Model S sedan. One version of the vehicle had a 75 kWh battery that would allow it to go 250 miles. But for $9,000 less, Tesla could change some code in the car’s computer to restrict the battery to 60 kWh and a range of 210 miles. It also offered 70 kWh options. People who bought one of the cheaper versions could pay for an upgrade later that unlocked the battery’s full potential. With the cheaper prices, Tesla hoped to capture more potential buyers and accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles.

Uber, the ride-sharing giant, has tried out premium pricing. The company is using machine learning to determine what a customer might be willing to pay for certain routes at particular times of the day, Daniel Graf, the company’s head of product, told Bloomberg this past May. Two customers leaving the same place at the same time and going the same distance might pay different prices based on their destinations. (And the customers and company can run into trouble, such as when a rider in December was charged $18,000 to go 11 miles.)

“It’s a technology, but it’s one that is the Holy Grail of its business model: Uber would love to charge everyone a price that’s individualized,” says Harvard’s Scott Kominers, who has written about the company for Bloomberg View. The strategy has some risk, as Uber has competition, but Kominers sees Uber as a company that could potentially walk the tightrope.

“If Uber introduces some new innovation that suddenly raises the prices for half of its customers, and if those customers are savvy, they might all switch to Lyft,” Kominers says. However, “Uber could use prior data to estimate how much you might pay and how likely you might be to respond to slight price increases. They could then, for example, try to price discriminate only to people who won’t switch over to Lyft.”

Facebook can already tell if you’ve started but failed to complete a purchase, say of a pair of shoes, on another site. A rival company can then run ads in your Facebook feed offering the same shoes, but maybe even cheaper. The digital data can follow shoppers into physical stores, as companies are using social media and emails to target chosen shoppers with coupons that shave a few dollars off the price of a product that those customers have come close to purchasing. In the future, says Misra, companies could be more discriminating about what they offer—and perhaps decide not to offer a discount if they know the customer purchases the product on a predictable schedule.

All this might have offended Wanamaker, who reportedly stated that “if everyone was equal before God, everyone should be equal before price.” But Wanamaker’s flagship store in Philadelphia is now a Macy’s, and department stores are struggling. His fortune was built on retail innovation, and if presented with a pricing scheme that could have nearly doubled his profits, it makes you wonder if he would have dismissed it—or given it a chance.

Jean-Pierre Dubé and Sanjog Misra, “Scalable Price Targeting,” Working paper, September 2017.

Research suggests a lesson for developers who want to convert existing users into paid subscribers.

How Do You Get People to Pay to Use a Mobile App?

Companies’ different strategies affect how prices change in a recession.

Will COVID-19 Lead to Lower Prices?

Research suggests the nutrition gap may be more a problem of demand than supply.

The Hole in the Food-Desert HypothesisYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.