Why the New Federal GMO Food Labels Are Unlikely to Affect Sales

Most consumers adjusted their buying patterns long before the national mandate.

Why the New Federal GMO Food Labels Are Unlikely to Affect SalesThe COVID-19 pandemic brought out people’s hoarding instinct. Since social distancing and sheltering in place became the norm, stores have been sold out of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and food staples as Americans worried about potential shortages buy ahead—and thereby create actual shortages.

Governments often worry that shortages will lead to price gouging. In fact, big retailers fear being accused of unfairly hiking prices, but their delay in increasing prices in response to demand spikes may actually contribute to hoarding, according to Imperial College London’s Christopher Hansman, Columbia’s Harrison Hong, University College London’s Aureo de Paula, and New York University’s Vishal Singh.

Humans have probably always engaged in hoarding, the researchers argue, but the role of modern marketplaces has been poorly understood, they write. To help rectify this, they studied consumer behavior in the United States during a 300 percent surge in global rice prices in 2008.

One of the challenges in studying hoarding has been a lack of granular, store-shelf-level data. Hansman, Hong, de Paula, and Singh mined the Nielsen Datasets at Chicago Booth’s Kilts Center for Marketing, drawing on a panel of more than 100,000 households that used handheld scanners to record every grocery-store purchase. The researchers extracted a sample covering 9,000 stores for 2007–09, with 1.1 million monthly observations of 42,000 households. This provided a window into US consumers’ behavior during the global rice crisis.

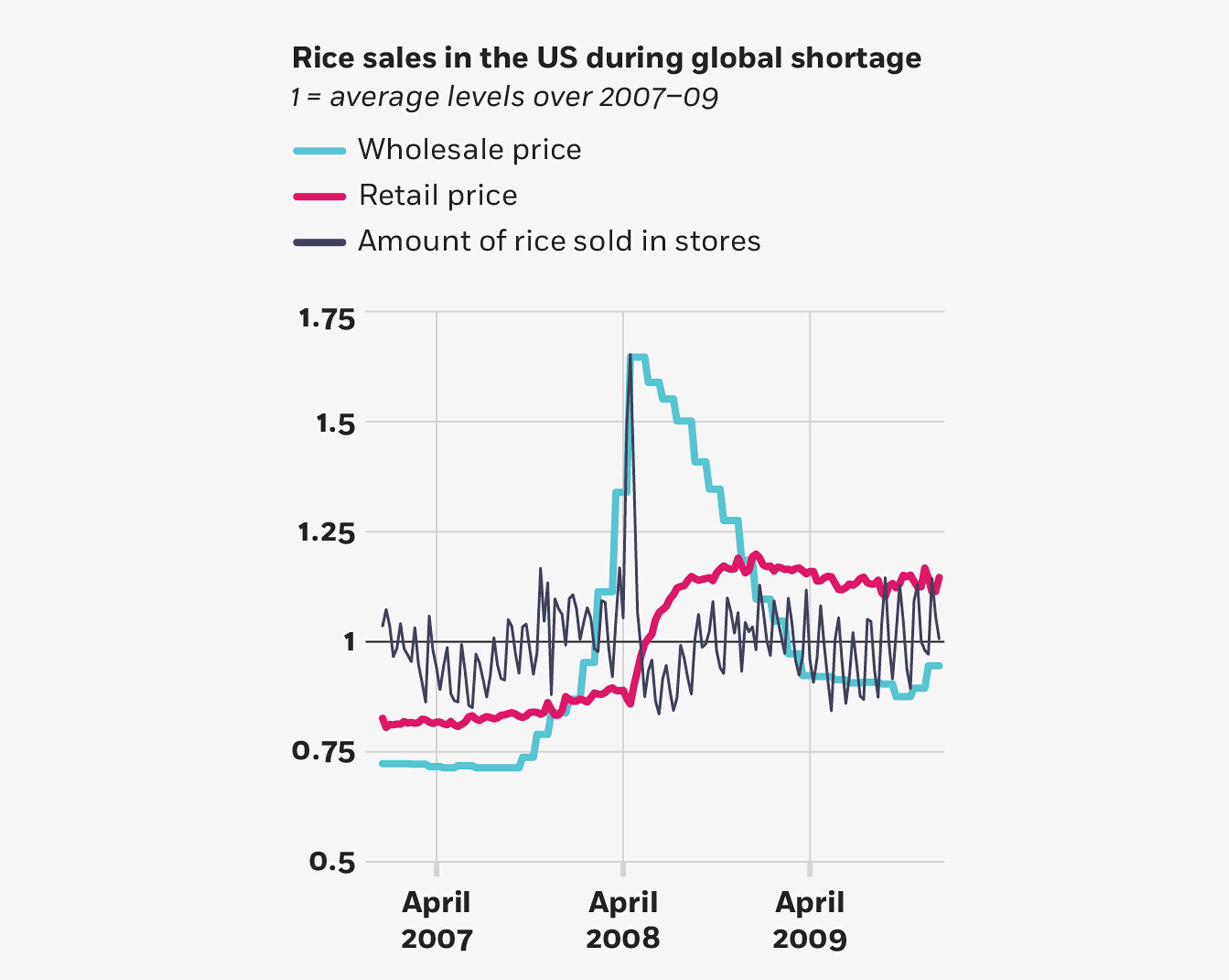

The crisis started with India’s politically motivated 2007 ban on rice exports, and continued until Japan agreed to release rice reserves to the world market in mid-2008. Amid media reports of hoarding and surging international prices, American consumers went on a rice-hoarding binge between mid-April and mid-May 2008, increasing purchases by 40 percent just as international wholesale prices peaked, the researchers find.

Store-level prices didn’t budge until much later, according to the study. This is consistent with extensive research documenting the “sticky prices” phenomenon in a modern national market dominated by giant retailing chains. After the hoarding period, store-level rice prices eventually climbed 23 percent, consistent with where wholesale costs finally settled on the global market, the data indicate. This effectively gave consumers a 23 percent discount, which the researchers calculate accounted for roughly half of the hoarding observed in the study.

By estimating household rice consumption and stockpiling, the researchers find that a handful of households may have tried to buy enough rice that they could resell it at a profit. But the vast majority of hoarding appeared to be for households’ own use.

There are two policy implications, the researchers write. First, governments needn’t particularly concern themselves with trying to regulate or crack down on price gouging by mainstream retailers. They observe that media reporting on COVID-19 hoarding and shortages suggests that attempts at profiteering mostly involve a small sample of opportunistic online resellers.

Secondly, what should concern policy makers is the finding that wealthier people bought more, while relatively low-income or otherwise vulnerable groups did less hoarding even as prices stayed flat, most likely because they lacked the resources, the researchers write. Consequently, controlling prices to prevent gouging won’t help people in these groups to retain access to necessities in hoarding episodes.

“Policies that ensure protected groups retain access to staples—as, for example, some grocery stores have done for the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic—should be considered within the regulatory toolkit,” the researchers write.

Christopher Hansman, Harrison Hong, Aureo de Paula, and Vishal Singh, “A Sticky-Price View of Hoarding,” Working paper, April 2020.

Most consumers adjusted their buying patterns long before the national mandate.

Why the New Federal GMO Food Labels Are Unlikely to Affect Sales

It isn’t just the quantity of goods that consumers buy but the quality that matters.

Why ‘Trading Down’ May Bias Our Picture of Inflation

The size of the pandemic’s economic shock, and the policy response to it, exceed many recent crises.

How the COVID-19 Recession Has Differed from the Great RecessionYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.