Capitalisn’t: Raghuram Rajan’s Vision of an Indian Path to Development

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan explains why India’s strengths play to services-based development.

Capitalisn’t: Raghuram Rajan’s Vision of an Indian Path to Development

Sebastien Thibault

When lawmakers ponder how to vote on a bill, there are any number of considerations they may have to juggle, including constituents, donors, special interests, party leadership, personal beliefs, and political expediency. But there may be another, more subtle force at work: their physical position within the legislative chamber.

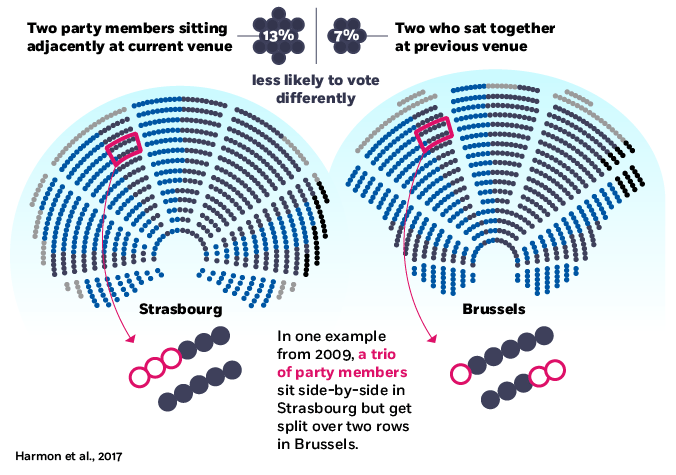

University of Copenhagen’s Nikolaj Harmon, Boston University’s Raymond Fisman, and Chicago Booth’s Emir Kamenica examined seating charts for the European Parliament to determine whether seating arrangements affect how members vote. They find that sitting adjacently makes it 13 percent less likely that two members of the same party will differ in their votes.

Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) belong to one of a handful of cross-national political parties, and when the parliament meets—usually in Strasbourg, France, but sometimes in Brussels—these groups sit together during voting (or “plenary”) sessions. Each member has an assigned seat within his or her party, usually based on alphabetical name order. Harmon, Fisman, and Kamenica consulted official seating charts for plenary sessions between 2006 and 2010 and mapped those seating arrangements to the votes cast by every MEP.

They find that not only were neighboring legislators more likely to vote alike, those peer effects persisted when MEPs who sat next to each other in one location (Strasbourg or Brussels) were seated apart in the other. Because seating rows end in different places in Brussels and Strasbourg, some alphabetically adjacent party members sit next to each other in Brussels but not Strasbourg, and vice versa. For instance, Yannick Jadot, Eva Joly, and Ska Keller—all MEPs from the Greens-European Free Alliance Group—sat in consecutive seats during the September–October 2009 plenary sessions in Strasbourg, but in Brussels, Keller sat in a different row due to variation in where seating rows ended.

By exploiting such variation in peer exposure over time, the research suggests that MEPs who sat next to each other during a prior plenary session are 7 percent less likely to disagree in a current session, regardless of whether the two members are currently sitting together.

Voting patterns persist despite different seating charts

European Parliament’s two venues seat members in alphabetical order, grouped by party. But the two seating layouts give many party members different neighbors at each site.

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan explains why India’s strengths play to services-based development.

Capitalisn’t: Raghuram Rajan’s Vision of an Indian Path to Development

Political philosopher Patrick Deneen discusses how to reorient the economic system for the common good.

Capitalisn’t: A Conservative Critique of Capitalism

Some can adversely affect companies’ productivity and other performance indicators.

Can Too Much Disclosure Hurt Profits and Innovation?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.