Is the FTC Targeting ‘Stealth Consolidation’ by Private Equity?

The agency has signaled increased scrutiny of nonreportable mergers in healthcare.

Is the FTC Targeting ‘Stealth Consolidation’ by Private Equity?

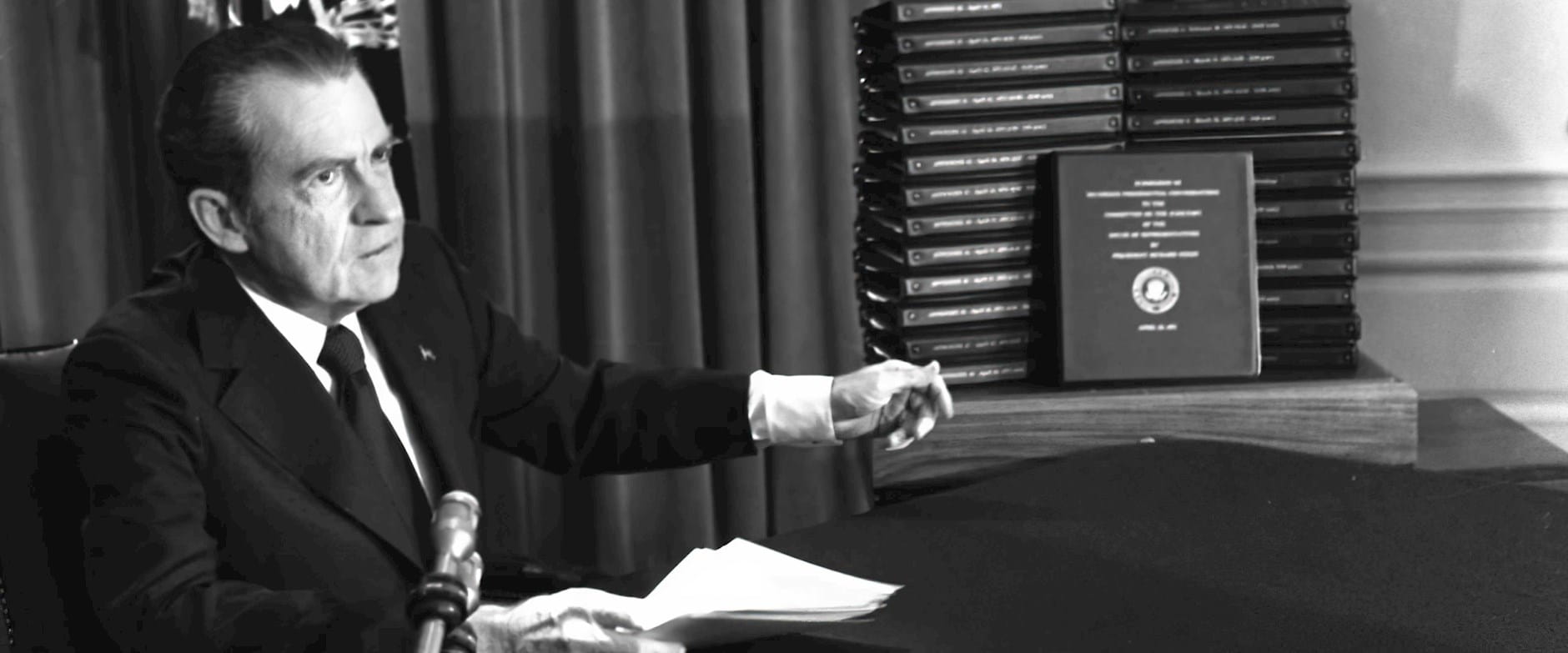

Associated Press

Scandals in the United States, and not least political scandals, have usually been short-term affairs. In most such instances, the press publishes the charges of wrongdoing with its accustomed fervent, if not noisome, self-righteousness. The accused is quickly condemned by the public, often removed from office, and soon forgotten, or else left to the long-drawn processes of the criminal law. In the latter event, the press coverage will be intense and titillating during the period of the trial, but also soon beyond the interest of the American public. Seldom do the cases involve more than the peccadilloes of a single, temporarily high-placed official; seldom do the cases present basic problems of a constitutional nature. The Watergate affair is different. It is different because the immediate criminal acts are but symptoms of a deeper and more fundamental ailment. It is different because it is not concerned with underlings, but with personages who once held the governance of the nation in their soiled hands. It is different because the essence of the wrongdoing is not to be found in the greed for money. It is different because it raises important constitutional questions, not least of which is, as President Nixon constantly reminds us, the question of the proper status of the presidency itself in our constitutional democracy. Not the XYZ affair (a diplomatic scandal of the 18th century), not the corruption of the Grant administration, not the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s, not all of them together cut so deep a wound in the American body politic. Even so, the immediate events of Watergate are not so threatening to our democracy as the more fundamental ailment of which Watergate is only a symptom. In his recent tour de force (1973’s The Imperial Presidency), in some ways an apologia pro vita sua, Arthur Schlesinger noted the terminal illness that threatens us:

For Watergate was a symptom, not a cause. Nixon’s supporters complained that his critics were blowing up a petty incident out of all proportion to its importance. No doubt a burglary at Democratic Headquarters was trivial next to a mission to Peking. But Watergate’s importance was not simply in itself. Its importance was in the way it brought to the surface, symbolized, and made politically accessible the great question posed by the Nixon administration in every sector—the question of presidential power. The unwarranted and unprecedented expansion of presidential power, because it ran through the whole Nixon system, was bound, if repressed at one point, to break out in another. This, not Watergate, was the central issue.

Clearly, Schlesinger is right in his analysis. But, possibly because he was an agent of earlier administrations, he did not see that the disease was contracted before Nixon came to power. The power of arrogance, the cancer that could kill our republic, was fully impregnated by the Kennedy administration, grew under the Johnson administration, and only achieved its culmination under Nixon.

Watergate is not a place, not a series of recent events, not a point in time. Watergate is a compendium whose most important element is a state of mind, an attitude about how American government should function. Watergate is also a question whether these United States can survive as a constitutional democracy.

Is it erroneous to suggest that the immediate events of Watergate began with the Pentagon Papers leak? Is it heresy to suggest that the evils that were revealed by the Pentagon Papers were wrongdoings of presidents Kennedy and Johnson and their advisors rather than those of President Nixon and his advisors? Is it inappropriate to notice that the “Plumbers” were President Nixon’s contribution to the scandals of the Pentagon Papers? Is it irrelevant to notice that the Bay of Pigs and the Central Intelligence Agency are integral parts of the Watergate scandal? Is it improper to suggest that Truman’s Korean venture is the direct precedent for the illegal war initiated by President Kennedy, stepped up by President Johnson, and continued to a delayed end by President Nixon? Is it bad taste to assert that the secret bombings of Cambodia were no more secret than the original use of advisors in Vietnam or the use of CIA mercenaries in Southeast Asia at an earlier date?

Watergate has brought the specter of totalitarianism to the attention of the American public.

For me, all these questions and more are necessary to the understanding of Watergate. Watergate did not occur as a biological sport. It is not a matter of yesterday, but of many yesterdays. Did money play a different role in the 1972 campaign than in the 1960 Democratic primaries and the contest that followed? Were the tactics that secured the nomination for the Democratic candidate in 1972, a candidacy that assured a Republican victory, more wholesome for our democratic institutions than those indulged by the Nixon campaign forces?

Watergate, however you define it, is a modern day Pandora’s box. The evils it has loosed are immeasurable. The problems it has raised are horrifying and apparently unsolvable. There are two different kinds of constitutional questions that derive from Watergate. The first are those constitutional issues that have engaged the attention of the news media and the public. Essentially these constitutional matters derive from questions of who is guilty of what, of how guilt is to be determined, and on what evidence. This kind of question has been, or probably will be, resolved by some appropriate tribunal.

The second set of constitutional questions is more important, if less sensational and therefore less noticed. These are concerned with the conditions that have made Watergate possible, i.e., with the present structure of our government and the problem of the survival of our democracy. These questions are likely to remain obscure and unresolved for want of attention or a proper forum, and with the great possibility of dire consequences.

George Washington’s decision not to be available for a third term as president of the US was announced in what we have all come to know as his Farewell Address. Every American schoolboy knows of the Farewell Address. And yet, it must be conceded that none of the advice so painstakingly offered in the address has been abided.

Washington warned against political parties, and they have come to dominate American affairs. He advised against “overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are now regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.” He admonished us that “it will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and at no distant period a great nation to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence.”

Included among his cautions was one that is particularly relevant to the subject of our discussion today. In 1796, he told us:

It is important . . . that the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration to confine themselves within their respective spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all departments in one, and this to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism. . . . If in the opinion of the people the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way in which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this in one instance may be the instrument of good; it is the customary weapon by which governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield.

We are governed today by a far different constitution than that which Washington bequeathed us. And the most basic changes have not been brought about by means of constitutional amendment, as Washington would have had it. We have seen the concentration of power in the presidency that has been achieved by the usurpation of which Washington warned us, aided largely by the abdication of responsibility by the Congress. We are, indeed, threatened by that despotism which he decried, whether it may be called “benevolent” or not.

Watergate, however, has brought the specter of totalitarianism to the attention of the American public. Now, as hardly ever before, we are cognizant of the crisis that we face. For the first time in many years, Congress is seeking to assert itself. The question is whether or not it is too late to restore the constitutional balance that our Founding Fathers created.

Heretofore, crisis has been the handmaiden of presidential power. Whether the crisis was economic, as was the case when Franklin Delano Roosevelt first came to power, or a military crisis of the kind that has plagued every generation of Americans, at least since World War I, it has always brought with it exaltation of executive authority. And each time, until the advent of the Vietnam War, this concentration of authority has been justified not only by our leading liberal politicians but also by our leading liberal scholars, either on the ground of necessity or expediency.

Since Roosevelt’s tenure, all meaningful government power has been vested in the national government. The only governmental powers that states now exercise are those allowed to them by the national government. State government is politically as well as economically bankrupt. And, within the national government, power has, since Roosevelt’s day, been concentrated in the executive branch. This is not a result of the Nixon incumbency.

As long ago as 1968, before Richard Nixon was elected to his first term as president of the US, Louis Heren, then Washington correspondent for the Times of London, wrote a perspicacious, if wrong-headed, book, which described the dominance of presidential power in American government in this fashion:

The modern American Presidency can be compared with the British monarchy as it existed for a century or more after the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215. . . . Indeed, it can be said that the main difference between the modern American President and a medieval monarch is that there has been a steady increase rather than a diminution of his power. In comparative historical terms the United States has been moving steadily backward.

The point I should like to make here, however, is that the dangers to American democracy and freedom against which George Washington warned lie not only in the adhesion of power to a single man, the president, but the adhesion of power to the executive office: an executive office that includes the National Security Council, the Council of Economic Advisers, the CIA, and the Office of Management and Budget among its unchecked, unlimited, and unelected “guardians” of the American people. To use Mr. Heren’s analogy, what we have witnessed in the Kennedy, the Johnson, and the Nixon administrations is a return to that period of English history when the power was not wielded solely by the king, but by the king and his council, to the period that led up to the American Revolution.

A startlingly perceptive and insightful work, Harvard Professor Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, published in 1967, demonstrates that the intellectual case for the American Revolution was based not so much on those simplifications about George III that are taught in our history courses, as on the notion that the English constitutional system on which all men’s liberties depended had been perverted by the men around the Crown in conjunction with the king rather than by the king alone. Read Bailyn’s words, and his use of the words of those who lived in the era that gave birth to our nation, and ask yourselves whether the explanation does not fit our day equally well:

The most common explanation, however, an explanation that rose from the deepest sources of British political thought, located “the spring and cause of all the distresses and complaints of the people in England or in America” in “a kind of fourth power that the constitution knows nothing of, or has not provided against.” This “overruling arbitrary power, which absolutely controls the King, Lords, and Commons,” was composed, it was said of the “ministers and favorites” of the King, who, in defiance of God and man alike, “exerted their usurped authority infinitely too far,” and “throwing off the balance of the constitution, make their despotic will” the authority of the nation.

For their power and interest is so great that they can and do procure whatever laws they please, having (by power, interest, and the application of the people’s money to placemen and pensioners) the whole legislative authority at their command . . . the rights of the people are ruined and destroyed by ministerial tyrannical authority and thereby . . . become a kind of slaves to the ministers of state.

This “junto of courtiers and state-jobbers,” these “court-locusts,” whispering in the royal ear, “instill in the King’s mind a divine right of authority to command his subjects” at the same time as they advance their “detestable scheme” by misinforming and misleading the people.

Bailyn also wrote, “For the primary goal of the American Revolution was . . . the preservation of political liberty threatened by the apparent corruption of the constitution.” The American Revolution was a political revolution, not a social or economic revolution. It was fought to restore the constitutional balance that Englishmen and Americans thought essential to the liberties they claimed. In the two centuries that have elapsed, the “corruption of the constitution,” which they deplored, has once again occurred. And, if our liberties are to be preserved, we should be looking to the means to restore the constitutional balance among the three branches of government.

The first step toward the restoration of our constitutional democracy would be the abolition of the “fourth branch of government”—to quote again from Bailyn’s sources—“a kind of fourth power that the constitution knows nothing of, or has not provided against.”

I don’t know yet when the euphemism “the White House” first came into use as a description of something other than the presidential mansion at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. But it was exactly when “the White House” became what it now is, a fourth branch of American government, that we were committed to take the road that led to Watergate. And this long journey probably began with the single step of the statutory authorization of Roosevelt in the Reorganization Act of 1939. Therefore, the first step back toward our constitutionally established democratic principles is to remove the powers accumulated in the so-called Executive Office of the President, to dissipate the Office of Management and Budget, the National Security Council, the Council of Economic Advisers, the czar of this and the emperor of that. Put these functions back in offices that are subject to congressional control and public scrutiny, or in administrative agencies that can be made totally free of Executive Office corruption.

The Founders had in mind not only a concept of the presidency but the kind of man they wanted.

Watergate, however, is the consequence not of one but of two kinds of corruption. The first is that which I have described as the “corruption of the constitution.” The second kind of corruption revealed by Watergate is the corruption of the people and particularly of individual officeholders. We have forgotten what a little-known Supreme Court justice, Noah Haynes Swayne, in a lesser-known Supreme Court case (Trust v. Child), once wrote: “The theory of our government is, that all public stations are trusts, and that those clothed with them are to be animated in the discharge of their duties solely by consideration of right, justice and the public good.”

The fact is, of course, that no institutions, however perfect, can function without the appropriate human beings to run them. The Founders had in mind not only a concept of the presidency but the kind of man they wanted when they prepared Article II. Despite their great respect for Washington, they limited the executive power as no national government had ever before limited executive power. The need for a Washington was, nevertheless, pervasively felt. The problem of finding the right men for the right governmental posts has long plagued us. The distinguished French historian François Guizot supplied the introduction to Jared Sparks’s biography of Washington. In 1837, Guizot wrote:

The disposition of the most eminent men, and of the best among the most eminent, to keep aloof from public affairs, in a free democratic society, is a serious fact. . . . It would seem as if, in this form of society, the tasks of government were too severe for men who are capable of comprehending its extent, and desirous of discharging the trust in a proper manner.

Today we are suffering not only from a corruption of the constitution through perversion of the institutions of government, but a corruption of the constitution because the men we have chosen for high office are unworthy. A US president who tells us that he is “not a crook” thereby affords little reassurance of his qualifications for office, even if we could still credit him with a capacity for the whole truth. It is not enough that the US president is “not a crook.” There is more to honor and duty than not stealing from the public fisc. The reassurance we need—and have not received, because deeds and not words are the only cogent evidence here—is that the authority of the US government is not expended merely to effectuate the personal whims or wishes of those in high authority nor to benefit their personal friends and do harm to their personal enemies. We live in an age when it is no longer the love of money that is the root of all evil; for our time, it is the love of power that is the root of all evil.

A system of presidential selection—not, incidentally, the one created by the constitution—that leaves the voters a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea, as it did in the 1972 election and in some earlier elections, helped bring us to this grievous point in our history. But that is another tale that requires another time for the telling, however short of time we may be.

The crisis called Watergate has provided us pain and suffering, outrage and disgust, fear and trembling. It has also afforded us an opportunity not likely to come again, to reexamine the “corruption of the constitution” from which we have been suffering these many years and to try to effect a remedy before it is too late.

Philip B. Kurland was William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the College and the Law School at the University of Chicago. He died in 1996.

The agency has signaled increased scrutiny of nonreportable mergers in healthcare.

Is the FTC Targeting ‘Stealth Consolidation’ by Private Equity?

Researchers piece together an explanation for the decline in US antitrust enforcement in recent decades.

What Made the Chicago School So Influential in Antitrust Policy?

Economists consider the effects of holding platforms more responsible for their users’ content.

How Would Increasing the Liability of Online Platforms Change the Internet?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.