By the same token, in the field of industrial relations, the possibility of challenge and response, from a base of some power on both sides, can be constructive. It provides an opportunity for people who have different backgrounds and orientations to bring out and represent their interests forcefully. Such representation can be productive, but it cannot take place if we do not allow for the possibility of a clash in views and the likelihood of an occasional explosion.

Second, we must all realize, whether as members of “the public” or in our private capacities, that we have a tremendous stake and a great interest in the vitality of private parties and private processes. If you have a management that is moribund and is not doing anything, or if you have a union that is lazy and is not representing its workers adequately, you really do not have a healthy situation at all. We want, instead, companies and unions who are alert, energetic, driving—who are analyzing their interests and representing them vigorously.

A good case in point is the railroads, where the government-dominated system of collective bargaining, at least until very recently, has fairly well sapped the vitality of the processes involved and has left the situation much worse than it otherwise might be. When it takes six years to settle a simple grievance, you surely have a bad situation.

Third, in this effort to suggest that the public has a stake in strikes other than only to get them settled, I offer you the great importance of having private parties be responsible, feel responsible, and take responsibility for the results of their efforts. Whatever settlement is reached—good, bad, or indifferent—somehow it must be their own settlement. It is the settlement of the people who have worked it out, not somebody else’s doing.

Finally, we must recognize that some strikes are simply part of the price we pay for free collective bargaining. If you tell people they are not allowed to strike or, in the case of management, take a strike, they are simply not free to pursue their interests as they see those interests. It is just one of the costs that goes with the gain of having a free system.

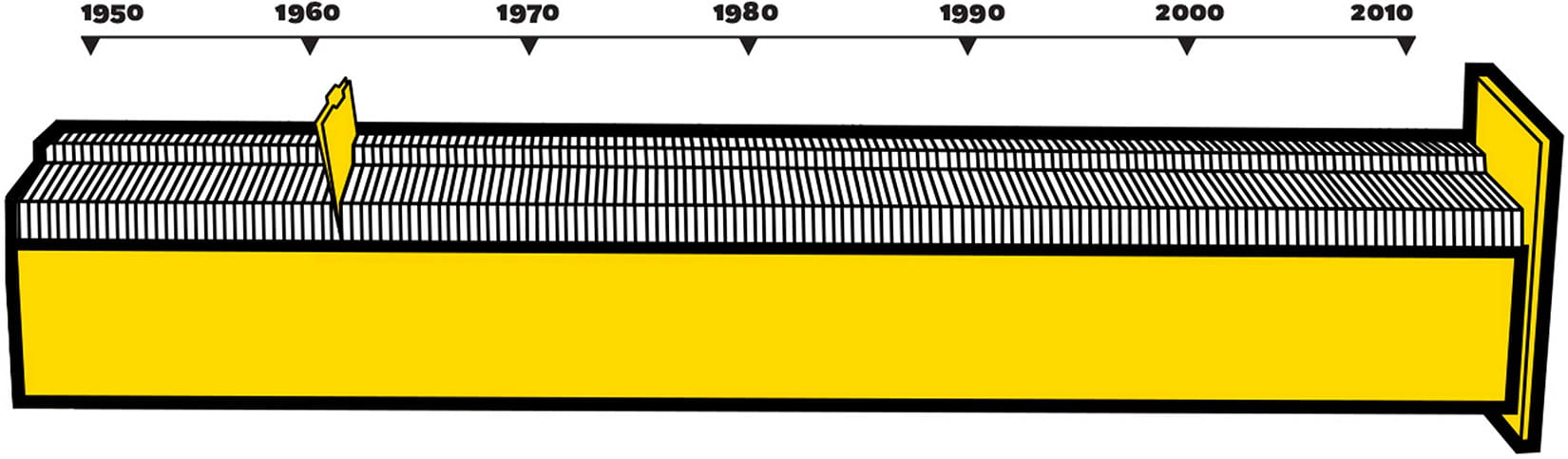

Now, of course, the greater the costs of labor-management conflict, the less happy we are to pay them. This point, then, is of great importance: the price we are paying for free bargaining in this country is an exceedingly small one, and we should not be reluctant to pay it.

The overstated consequences of strikes

Now, perhaps you will say that the recent longshore strike, in which a Taft-Hartley Act injunction was used, is a case against me. That may be, but I think it is worth noting that the president sought and got an injunction against such a strike on the grounds that, if the strike were permitted to occur, it would create a national emergency. But after the injunction expired, a strike did run for over one month, and what did people talk about? All I read about in the Wall Street Journal was the bananas: you are not going to get bananas; they are doubling in price. Just for fun, one morning in New York after the strike had been on some weeks, I ordered bananas with my shredded wheat to see if they would come. The waiter didn’t even give me an argument; he brought the bananas. This is not to deny the genuine economic hardship and public inconvenience that can be caused by a prolonged strike on the docks or in some other industries. But the allegations of hardship need the closest scrutiny, and the true costs must be balanced against the price of intervention.

My point is that the public has vital interests in allowing people freedom to strike—or take a strike—if they want to, and if these interests are disregarded, the system of industrial relations is going to change very drastically.

Furthermore, in taking this position, at least in this day and age, we are really not taking such a terrible risk, because the volume and the impact of strikes are not nearly so great as alleged. Most goods and services turn out to have fairly close substitutes, which, indeed, is one reason for prompt settlement of most disputes. Or, alternatively, inventories may provide a considerable hedge against the impact of a strike. There are problems, of course, but they are far overrated, and the health and safety aspects are usually not present.

The danger of government intervention

The present course of national policy has seemed, at least until very recently, to be: intervene early; intervene with preconceptions of what the right answer is; and intervene frequently, over a wide scale, with high officials. And now the picture is further complicated by the fact that Congress, albeit reluctantly, is in the act.

I do not think that is a considered policy but is just what has happened. That is in a sense the effective policy we have, and it has been born out of all sorts of frustrations, out of all sorts of problems arising from the structure and issues of collective bargaining.

This process also demands solutions. If you are going to take the intervention route, you have to provide the answer. If parties feel they are not getting what they want through bargaining, they are certainly going to find out what the government’s answer is and try to use that leverage as much as possible. This can ruin private bargaining because it forces each party to hold back any concessions that might normally be made. Anything you concede will be held against you in the next, higher round of discussions.